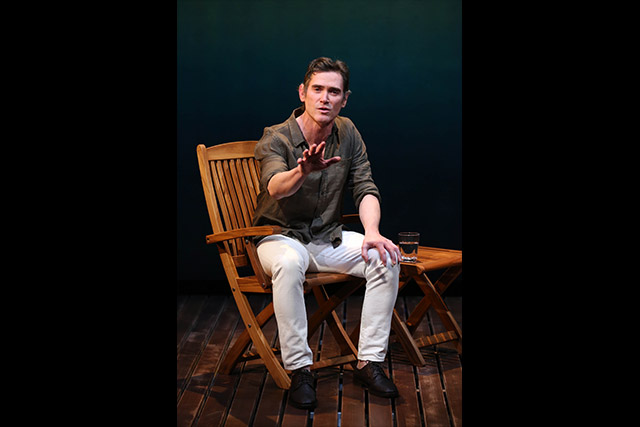

Tony winner Billy Crudup stars as a man in search of his genuine identity in Harry Clarke (photo by Carol Rosegg)

Vineyard Theatre

Gertrude and Irving Dimson Theatre

108 East 15th St. between Union Square East & Irving Pl.

Extended through December 23, $120

www.vineyardtheatre.org

Tony winner Billy Crudup charms the audience much as the character he plays charms the Schmidt family in David Cale’s riveting one-man show, Harry Clarke. In his first solo performance, Crudup is captivating as Philip Brugglestein, a wayward midwesterner who invented an alter ego, the British-speaking Harry Clarke, as a psychological defense against bullying schoolmates and his mentally and physically abusive father. As an adult, Philip has moved to New York City, where he is floundering. One day, in the mood for an adventure, he follows a random guy in the street; later, he befriends the man, a wealthy financier named Mark Schmidt, but Philip introduces himself as his childhood creation, pretending to be the fun-loving Harry Clarke, a smooth operator from Elstree. (He even claims that he worked for Sade for twenty years.) Harry insinuates himself into Mark’s life, as well as that of Mark’s sister, Stephanie, and mother, Ruth, in a way reminiscent of Tom Ripley in Patricia Highsmith’s books except Harry is no mere con man out for money; he’s seeking connections, searching for his identity, as are most of the characters in the play. “I could be myself if I had an English accent,” he recalls saying as child, later telling his parents, “But it’s my real voice.” Soon Harry finds himself caught up in a situation that he didn’t quite expect.

Billy Crudup voices multiple characters in world premiere of David Cale one-man show at the Vineyard (photo by Carol Rosegg)

An actor, composer, and playwright who was born in London and moved to New York when he was twenty, Cale originally wrote Harry Clarke for himself — he has previously written and starred in such solo works as Lillian, Deep in a Dream of You, and The Redthroats and has appeared on The Good Wife and in The Total Bent at the Public — but he eventually opted for Crudup, who has been nominated for four Tonys, winning one (for The Coast of Utopa), and has had major roles in such films as Almost Famous and Jesus’ Son. In his third play at the Vineyard, following Chiori Miyagawa’s America Dreaming and Adam Rapp’s The Metal Children, Crudup commands the virtually bare stage with a tender fury; Alexander Dodge’s set features a lone chair on a deck, a small table where Crudup keeps a glass of water, and a scrim in back for abstract projections that hint at a blue sea and sky, with occasional changes. Two-time Obie winner and Tony nominee Leigh Silverman (Violet, In the Wake), who directed Marin Ireland in the searing one-woman show On the Exhale earlier this year, knows just when to get Crudup on the move. Crudup (Waiting for Godot, No Man’s Land) sits casually before at last getting up and really hitting his stride, doing different voices for every character; the writing is so sharp, and the performance so astute, with a cinematic fervor, that you can easily visualize the places Harry goes, from Sixth Ave. to a gay bar to relaxing on board the Schmidts’ boat, Jewish American Princess. Harry is a big movie fan, preferring noirs and thrillers and listening to records by French film composer Georges Delerue, and Cale’s play becomes like a noir thriller itself; it’s no coincidence that Mark wants to become a movie producer. When Harry and Mark meet for the second time, in a theater, Harry says, “This play’s like a mystery, in that sense, seems more like a movie.” Meanwhile, Philip, of course, is a completely unreliable narrator; all of the events are related through his warped, damaged, unpredictable view, as if he’s created his own movie, but that’s part of what makes the show so tantalizing.