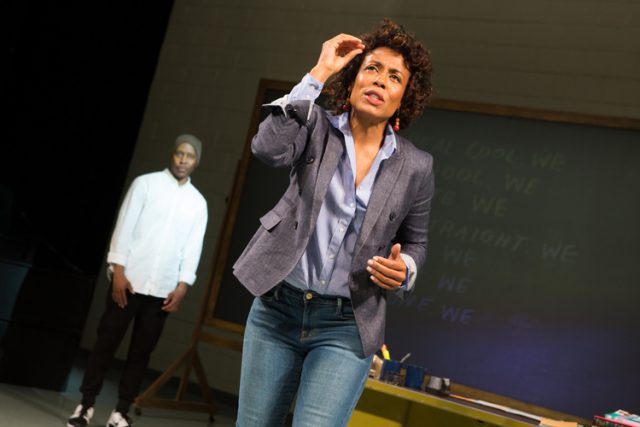

Nya (Karen Pittman) desperately tries to protect her son, Omari (Namir Smallwood), in Dominique Morisseau’s riveting Pipeline (photo by Jeremy Daniel)

Lincoln Center Theater at the Mitzi E. Newhouse

150 West 65th St. between Broadway & Amsterdam Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through August 27, $87

212-362-7600

www.lct.org

Pipeline is an up-to-the-minute, honest, and hard-hitting look at race, class, and the education system in the United States from Detroit native Dominique Morisseau. Continuing at the Mitzi E. Newhouse through August 27, the intensely intelligent, powerful play was created by Morrisseau shortly after completing her award-winning Detroit Projects trilogy (Detroit ’67, Paradise Blue, Skeleton Crew) and before she begins her Residency Five at the Signature Theatre in April 2018 with a revival of Paradise Blue. In this new work, Morisseau brilliantly introduces Nya (Karen Pittman), a divorced public-school teacher in an unidentified city facing a family crisis, as she leaves a complicated, heart-rending phone message for her ex-husband, Xavier (Morocco Omari), explaining in fractured sentences that their son, Omari (Namir Smallwood), is facing explusion from school. However, she decides to delete the message, replacing it with a blunt “Calling to talk to you about our son. Give me a call back when you get this. Thanks. Bye.” In the span of just a few minutes, Morisseau has set the stage beautifully, establishing character, plot, and mood. Omari is a dour teenager who has attacked one of his teachers during a discussion about Richard Wright’s Native Son, an incident that was captured on video and is about to go viral. Omari’s girlfriend, Jasmine (Heather Velazquez), is a whirling dervish of opinions who’s never afraid to say what she is thinking. Meanwhile, Nya’s fellow teacher, the bitter, old-fashioned Laurie (Tasha Lawrence), has returned to school after getting involved in a serious fight between two students. “A good old ass whipping can teach a lot,” she says. The teachers are sometimes joined by Dun (Jaime Lincoln Smith), a flirtatious school security guard who promises Nya and Laurie that he’ll do whatever he can to prevent further clashes with students. But when Omari runs off, Nya becomes desperate to find him before his future comes crashing down. It’s all summed up by Jasmine, who tells Nya, “Sometimes somebody mess with you on the wrong day. . . . It’s like THEY don’t know it’s your last straw. But they ain’t seen how many times you been sucked of everything you got. They go pickin’ at you like lint, and be lookin’ surprised when you knock ’em flat the hell out.”

Jasmine (Heather Velazquez) and Omari (Namir Smallwood) face a troubling situation in poetic Lincoln Center production (photo by Jeremy Daniel)

Nya occasionally addresses the audience directly, as if they are in class themselves, but Morisseau, a former teacher whose mother was a public school teacher, and Obie-winning director Lileana Blain-Cruz (War, The Death of the Last Black Man in the Whole Entire World) never allow the play to become overly preachy or pedantic. (There’s even a program insert, “Playwright’s Rules of Engagement,” which notes, “This can be church for some of us, and testifying is allowed.”) The set, by Matt Saunders, swiftly changes from office to lunchroom to dorm room to classroom to hospital waiting room, with occasional scenes taking place in what Morisseau, who is also a writer and executive story editor for the Showtime series Shameless, calls “undefined space.” Omari’s fight with his teacher is representative in many ways of the confrontations between police and black and brown men and the need for personal space, and it’s all sensitively portrayed by an exceptionally strong cast and exceptional writing. “It’s a gamble, Jasmine,” Nya says. “All the time. You send your young man out into the world everyday, or away for a weekend. A semester. A school year. But you don’t know . . . You have no idea if they’re safe. You have no idea if one day someone will try to expire them because they are too young. Or too Black. Or too threatening. Or too loud. Or too uninformed. Or too angry. Or too quiet. Or too everyday. Or too cool. Or too uncomposed. Or too mysterious. Or just too TOO. You don’t know, Jasmine.” The relationships between the characters are fully believable as Morisseau steers clear of genre clichés in making the many issues Pipeline raises a microcosm of what is happening in twenty-first-century America. And at the center of it all is Gwendolyn Brooks’s 1960 poem “We Real Cool,” which is projected onto a blackboard and adorns the cover of Lincoln Center Theater Review: “We real cool. We / Left school. We / Lurk late. We / Strike straight. We / Sing sin. We / Thin gin. We / Jazz June. We / Die soon.” Pipeline is a poetic indictment of institutionalized societal constraints, a lesson we all need to learn.