Kaji (Tatsuya Nakadai) has to search hard to find the humanity in the world in Masaki Kobayashi three-part masterpiece (photo © Shochiku Co., Ltd.)

THE HUMAN CONDITION (Masaki Kobayashi, 1959-61)

Museum of the Moving Image

35th Ave. at 36th St., Astoria

Part I: Saturday, May 16, $15, 1:00

Part II: Saturday, May 16, $12, 6:00

Part III: Sunday, May 17, $12, 1:00

Series runs May 15-24

718-777-6800

www.movingimage.us

Masako Kobayashi’s ten-hour epic, The Human Condition, based on a popular novel by Jumpei Gomikawa, is one of the most stunning achievements ever captured on film, and you can catch it all this weekend at the Museum of the Moving Image. Shot over the course of three years, the film follows one man’s harrowing struggle to never give up his humanity as he is dragged deeper and deeper into the morass of WWII. Tatsuya Nakadai is remarkable as Kaji, a man who believes in common decency, personal discipline, and, above all else, that humanity will always triumph. In the first part, No Greater Love, the steadfastly practical Kaji is hesitant to marry his sweetheart, Michiko (Michiyo Aratama), for fear that he will be called to serve in the Japanese army and might not come back to her alive. But when his detailed plan to treat workers fairly is accepted by the government, he is made labor supervisor of a mine in far-off Southern Manchuria, where hundreds of Chinese prisoners are brought in as well — and regularly starved, beaten, and, on occasion, brutally killed in cold blood. Kaji’s methods, which have close ties to communism, leading many to refer to him as a “Red,” anger both sides — the Japanese want to treat the workers like animals, and the Chinese prisoners don’t trust that he has their welfare in mind. A series of escape attempts threatens the stability of the labor camp and comes between Kaji and Michiko, whose undying love is echoed in the yearning, unfulfilled desire between a Korean prisoner and a Japanese prostitute. Broken promises, lies, and betrayal reach a tense conclusion that sets the stage for the second part of Kobayashi’s masterpiece.

Masako Kobayashi’s ten-hour epic, The Human Condition, based on a popular novel by Jumpei Gomikawa, is one of the most stunning achievements ever captured on film, and you can catch it all this weekend at the Museum of the Moving Image. Shot over the course of three years, the film follows one man’s harrowing struggle to never give up his humanity as he is dragged deeper and deeper into the morass of WWII. Tatsuya Nakadai is remarkable as Kaji, a man who believes in common decency, personal discipline, and, above all else, that humanity will always triumph. In the first part, No Greater Love, the steadfastly practical Kaji is hesitant to marry his sweetheart, Michiko (Michiyo Aratama), for fear that he will be called to serve in the Japanese army and might not come back to her alive. But when his detailed plan to treat workers fairly is accepted by the government, he is made labor supervisor of a mine in far-off Southern Manchuria, where hundreds of Chinese prisoners are brought in as well — and regularly starved, beaten, and, on occasion, brutally killed in cold blood. Kaji’s methods, which have close ties to communism, leading many to refer to him as a “Red,” anger both sides — the Japanese want to treat the workers like animals, and the Chinese prisoners don’t trust that he has their welfare in mind. A series of escape attempts threatens the stability of the labor camp and comes between Kaji and Michiko, whose undying love is echoed in the yearning, unfulfilled desire between a Korean prisoner and a Japanese prostitute. Broken promises, lies, and betrayal reach a tense conclusion that sets the stage for the second part of Kobayashi’s masterpiece.

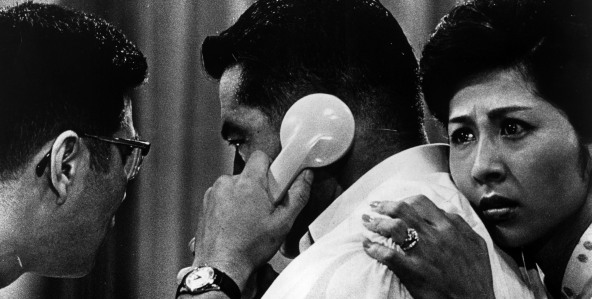

Michiyo Aratama and Tatsuya Nakadai hope that love trumps all in antiwar epic (photo © Shochiku Co., Ltd.)

SPOILER ALERT: Skip the next paragraph if you don’t want to know what happens in parts II & III!

In Road to Eternity, Kaji has been drafted into the Kwantung Army, going through basic training in preparation for battle. Kaji hopes to find some semblance of humanity in the army, but the superiors are constantly slapping and hitting the recruits, punishing them in brutal ways. When Michiko suddenly shows up, Kaji suffers harassment as it is being decided whether he will be allowed to spend the night with her. With the Soviets on the march, a firefight beckons, but the Japanese troops are woefully short on weapons and ammunition — and confidence, with rumors of Japan’s demise rampant. The epic concludes with the powerful, emotional A Soldier’s Prayer. Kaji is determined to make it back to Michiko, even if it means desertion, but a long, treacherous trip awaits him and he is dangerously low on supplies. He is trying desperately to hang on to his dignity and humanity, but it becomes more and more difficult as the weather worsens, hopelessly lost people join him through the forest, and food is nowhere in sight.

The Human Condition, which has had a profound influence on such filmmakers as Stanley Kubrick, Steven Spielberg, Andrei Tarkovsky, and so many others, might take place during WWII, with Japan fighting for the Axis powers while also immersed in the Second Sino-Japanese War, but its story about man’s inhumanity to man is timeless. At its core, it’s not about Fascism, socialism, democracy, and ethnocentricity but humankind’s need for love and truth. Kaji and Michiko represent everyman and everywoman, separated by a cruel, cold world. Kobayashi provides no answers — the future he envisions is bleak indeed. At Film Forum a few years back for a tribute to his career, Nakadai talked about how brutal the making of The Human Condition was — it is also brutal to sit through, but it is a landmark work that must be seen. All three parts of the film are being shown May 16-17 at the Museum of the Moving Image in “Portraying the Human Condition: The Films of Masaki Kobayashi and Tatsuya Nakadai,” a ten-day series of nine works the pair made together, including Black River, The Inheritance, Kwaidan, Samurai Rebellion, Strike a Life for Nothing, and Harakiri. Nakadai will be at the museum to discuss his work at the May 16 screening of No Greater Love and the May 24 showing of Harakiri.

Kôbô Abe and director Hiroshi Teshigahara collaborated on five films together, including the marvelously existential Woman of the Dunes in 1964 and The Face of Another two years later. In The Face of Another, Tatsuya Nakadai (The Human Condition, Kill!) stars as Okuyama, a man whose face has virtually disintegrated in a laboratory accident. He spends the first part of the film with his head wrapped in bandages, a la the Invisible Man, as he talks about identity, self-worth, and monsters with his wife (Machiko Kyo), who seems to be growing more and more disinterested in him. Then Okuyama visits a psychiatrist (Mikijirô Hira) who is able to create a new face for him, one that would allow him to go out in public and just become part of the madding crowd again. But his doctor begins to wonder, as does Okuyama, whether the mask has actually taken control of his life, making him as helpless as he was before. Abe’s remarkable novel is one long letter from Okuyama to his wife, filled with utterly brilliant, spectacularly detailed examinations of what defines a person and his or her value in society. Abe wrote the film’s screenplay, which tinkers with the time line and creates more situations in which Okuyama interacts with people; although that makes sense cinematically, much of Okuyama’s interior narrative, the building turmoil inside him, gets lost. Teshigahara once again uses black and white, incorporating odd cuts, zooms, and freeze frames, amid some truly groovy sets, particularly the doctor’s trippy office, and Tōru Takemitsu’s score is ominously groovy as well. As a counterpart to Okuyama, the film also follows a young woman (Miki Irie) with one side of her face severely scarred; she covers it with her hair and is not afraid to be seen in public, while Okuyama must hide behind a mask. But as Abe points out in both the book and the film, everyone hides behind a mask of one kind or another. The Face of Another is having a special screening May 17 at 3:00 at the Museum of the Moving Image and will be followed by a conversation between Nakadai and Terrence Rafferty; advance tickets are available now.

Kôbô Abe and director Hiroshi Teshigahara collaborated on five films together, including the marvelously existential Woman of the Dunes in 1964 and The Face of Another two years later. In The Face of Another, Tatsuya Nakadai (The Human Condition, Kill!) stars as Okuyama, a man whose face has virtually disintegrated in a laboratory accident. He spends the first part of the film with his head wrapped in bandages, a la the Invisible Man, as he talks about identity, self-worth, and monsters with his wife (Machiko Kyo), who seems to be growing more and more disinterested in him. Then Okuyama visits a psychiatrist (Mikijirô Hira) who is able to create a new face for him, one that would allow him to go out in public and just become part of the madding crowd again. But his doctor begins to wonder, as does Okuyama, whether the mask has actually taken control of his life, making him as helpless as he was before. Abe’s remarkable novel is one long letter from Okuyama to his wife, filled with utterly brilliant, spectacularly detailed examinations of what defines a person and his or her value in society. Abe wrote the film’s screenplay, which tinkers with the time line and creates more situations in which Okuyama interacts with people; although that makes sense cinematically, much of Okuyama’s interior narrative, the building turmoil inside him, gets lost. Teshigahara once again uses black and white, incorporating odd cuts, zooms, and freeze frames, amid some truly groovy sets, particularly the doctor’s trippy office, and Tōru Takemitsu’s score is ominously groovy as well. As a counterpart to Okuyama, the film also follows a young woman (Miki Irie) with one side of her face severely scarred; she covers it with her hair and is not afraid to be seen in public, while Okuyama must hide behind a mask. But as Abe points out in both the book and the film, everyone hides behind a mask of one kind or another. The Face of Another is having a special screening May 17 at 3:00 at the Museum of the Moving Image and will be followed by a conversation between Nakadai and Terrence Rafferty; advance tickets are available now.