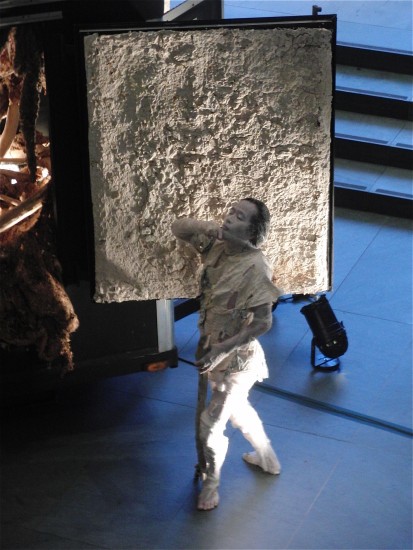

Career retrospective offers a dazzling look into the surreal world of the Brothers Quay (still from STREET OF CROCODILES, 1986)

Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53rd St. between Fifth & Sixth Aves.

Wednesday–Monday through January 7

Museum admission: $22.50 ($12 can be applied to the purchase of a film ticket within thirty days)

212-708-9400

www.moma.org

When MoMA Film associate curator Ron Magliozzi first approached twins Stephen and Timothy Quay about putting together a career retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, the brothers weren’t sure why people would be interested in delving into their history and working process, but they opened their London studio to Magliozzi and helped design the appropriately strange and wonderful exhibit “On Deciphering the Pharmacist’s Prescription for Lip-Reading Puppets.” Similar in concept to the “Tim Burton” blockbuster a few years back, the Quay Brothers show is filled with paintings and drawings, film and video, early self-portraiture, photographs, collages, book and album covers, etchings, engravings, commercials, and other fascinating paraphernalia associated with their rather eclectic career, spread across several floors. Born in rural Pennsylvania in 1947 to a machinist father and homemaker mother, the Quays were heavily influenced by illustrator and naturalist Rudolf Freund, whom they met in the late 1960s; Polish poster art from the 1960s, which they saw in a 1967 exhibition at the Philadelphia College of Art; and avant-garde, experimental shorts by Jan Lenica and Walerian Borowczyk.

Quay Brothers, detail, “O Inevitable Fatum, Rehearsals for Extinct Anatomies, décor,” wood, fabric, glass, metal, 1987 (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

The MoMA show is set up like a labyrinth, with treats around every corner, from oil snowscapes done when the brothers were still in single digits to short films made when they were in school, from the creepy Black Drawings of the mid-1970s and stage designs for opera, theater, and dance by Béla Bartók, Eugene Ionesco, Molière, Sergei Prokofiev, Georges Feydeau, E. T. A. Hoffman, and others to their British television documentaries, made with longtime producer Keith Griffiths and including the absolutely insane documentary Igor, the Paris Years Chez Pleyel, in which paper cut-outs of Bolshevik poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, French writer and filmmaker Jean Cocteau, and Russian-born composer Igor Stravinsky hang out and do rather odd things in Paris. All of these works lend intrigue and insight to the primary sections of the exhibition, dedicated to the marvelous short films the Quays are renowned for, dark, dazzling stop-motion animations with puppets that relate mesmerizing tales set in a mysterious world of dreams and nightmares that delve into the subconscious. The Quay Brothers’ breakthrough came in 1986 with Street of Crocodiles, adapted from a Bruno Schulz short story, starring eyeless puppets with open heads and taking place in a Kinetoscope, featuring themes and elements that appear in many of their films, including machines, thread, scissors, repetitive movement, screws, bones, metal shavings, and aching, experimental music. Getting its own room, the film is followed by a two-minute outtake that has never been shown before. Among the many other classic Brothers Quay shorts on view in the galleries are In Absentia, The Cabinet of Jan Svankmajer, Rehearsals for Extinct Anatomies, The Sandman, and the dazzling color films This Unnameable Little Broom and The Comb (from the Museums of Sleep). Downstairs outside the Titus Theaters is “Dormitorium,” a terrific collection, previously seen at Parsons the New School for Design in 2009, of film décors, glass-enclosed sets from many of the above-mentioned films as well as many others. And on the first floor by the up escalator you can find “Coffin of a Servant’s Journey,” a short film inside a coffin that can be watched by only one person at a time.

Quay Brothers, “Quay Brothers self-portrait,” photographic enlargement (Atelier Koninck QbfZ)

“On Deciphering the Pharmacist’s Prescription for Lip-Reading Puppets” is a magical trip inside the bizarre, surreal world of the Quay Brothers, an exhibition that was a long time coming and has been handled splendidly. It’s also an exhibition that requires a lot of time to be properly enjoyed, so don’t rush through it or you’ll miss so many of its myriad hidden treasures. And as far as the title itself goes, we’ll leave that to the Quays to describe themselves, as they do in the catalog in a faux interview with sixteenth-century composer Heinrich Holtzmüller: “In our mind it’s more of a teasing inducement for a journey. Not a grand journey but a tiny one . . . around the circumference of an apple. We’re no doubt gently abusing the anticipation that the prescriptive side is courting both a rational illegibility as well as an irrational legibility. Hopefully the intrigued will engage with the ambiguity. And besides, the prescription is only mildly inscrutable and one certainly won’t die from it, considering that thousands of people a year reportedly die from misread prescriptions.” You were expecting anything different?

(MoMA will be screening the Quay Brothers’ latest full-length film, Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, on January 6-7 in Titus Theater 1, with a live musical score performed by Mikhail Rudy. Also on January 7, “The Essential Shorts, Part 2” will screen six shorts in the Education and Research Building, including Rehearsals for Extinct Anatomies, Nocturna Artificialia, Ex Voto, This Unnameable Little Broom: Epic of Gilgamesh, Maska, and Bartók Béla: Sonata for Solo Violin.)

We used to think that Aki Kaurismäki’s The Match Factory Girl was the saddest film ever made about a young woman who just can’t catch a break, as misery after misery keeps piling up on her ever-more-pathetic existence. But the Finnish black comedy has nothing on Kenji Mizoguchi’s The Life of Oharu, a searing, brutal example of the Buddhist observation of impermanence and the role of women in Japanese society. The film, based on a seventeenth-century novel by Ihara Saikaku, is told in flashback, with Oharu (Kinuyo Tanaka) recounting what led her to become a fifty-year-old prostitute nobody wants. It all starts to go downhill after she falls in love with Katsunosuke (Toshirô Mifune), a lowly page beneath her family’s station. The affair brings shame to her mother (Tsukie Matsuura) and father (Ichiro Sugai), as well as exile. The family is redeemed when Oharu is chosen to be the concubine of Lord Matsudaira (Toshiaki Konoe) in order to give birth to his heir, but Lady Matsudaira (Hisako Yamane) wants her gone once the baby is born, and so she is sent home again, without the money her father was sure would come to them. Over the next several years, Oharu becomes involved in a series of personal and financial relationships, each one beginning with at least some hope and promise for a better future but always ending in tragedy. Nevertheless, she keeps on going, despite setback after setback, bearing terrible burdens while never giving up. Mizoguchi (Sansho the Bailiff, The 47 Ronin, Street of Shame) bathes much of the film in darkness and shadow, casting an eerie glow over the unrelentingly melodramatic narrative. Tanaka, who appeared in fifteen of Mizoguchi’s films and also became the second Japanese woman director (Love Letter, Love Under the Crucifix), gives a subtly compelling performance as Oharu, one of the most tragic figures in the history of cinema. Winner of the International Prize at the 1952 Venice International Film Festival, The Life of Oharu is screening September 3 at 4:30 as part of MoMA’s “An Auteurist History of Film Reprise,” which gives film enthusiasts a second chance to catch works that have previously been shown at MoMA at earlier hours in the day, when many people cannot see them.

We used to think that Aki Kaurismäki’s The Match Factory Girl was the saddest film ever made about a young woman who just can’t catch a break, as misery after misery keeps piling up on her ever-more-pathetic existence. But the Finnish black comedy has nothing on Kenji Mizoguchi’s The Life of Oharu, a searing, brutal example of the Buddhist observation of impermanence and the role of women in Japanese society. The film, based on a seventeenth-century novel by Ihara Saikaku, is told in flashback, with Oharu (Kinuyo Tanaka) recounting what led her to become a fifty-year-old prostitute nobody wants. It all starts to go downhill after she falls in love with Katsunosuke (Toshirô Mifune), a lowly page beneath her family’s station. The affair brings shame to her mother (Tsukie Matsuura) and father (Ichiro Sugai), as well as exile. The family is redeemed when Oharu is chosen to be the concubine of Lord Matsudaira (Toshiaki Konoe) in order to give birth to his heir, but Lady Matsudaira (Hisako Yamane) wants her gone once the baby is born, and so she is sent home again, without the money her father was sure would come to them. Over the next several years, Oharu becomes involved in a series of personal and financial relationships, each one beginning with at least some hope and promise for a better future but always ending in tragedy. Nevertheless, she keeps on going, despite setback after setback, bearing terrible burdens while never giving up. Mizoguchi (Sansho the Bailiff, The 47 Ronin, Street of Shame) bathes much of the film in darkness and shadow, casting an eerie glow over the unrelentingly melodramatic narrative. Tanaka, who appeared in fifteen of Mizoguchi’s films and also became the second Japanese woman director (Love Letter, Love Under the Crucifix), gives a subtly compelling performance as Oharu, one of the most tragic figures in the history of cinema. Winner of the International Prize at the 1952 Venice International Film Festival, The Life of Oharu is screening September 3 at 4:30 as part of MoMA’s “An Auteurist History of Film Reprise,” which gives film enthusiasts a second chance to catch works that have previously been shown at MoMA at earlier hours in the day, when many people cannot see them.

Ben Affleck, who displayed great skill as a director in his debut feature, 2007’s Gone Baby Gone, did it again with his follow-up, the romantic thriller The Town. Affleck, who also cowrote the script, stars as Doug MacRay, the leader of a small group of bank robbers in tough Charlestown, Massachusetts, the bank robbery capital of America. As the film opens, the thieves are just hitting a bank and are forced to take a hostage, manager Claire Keesey (Rebecca Hall). After later letting her go unharmed, they soon realize that she lives in their neighborhood and might be able to recognize one of them, so Doug starts hanging around her, pretending to be interested in her so he can tap her for information. Meanwhile, Boston cop Dino (Titus Welliver) and FBI Special Agent Frawley (Jon Hamm) are getting closer to the gang, who continue to pull off daring heists regardless of the heat on them. Although there are a handful of plot holes you could drive an armored truck through, The Town ends up being a compelling action film and love story, with car chases, massive shootouts, and a tender relationship as Doug begins to fall for Claire, and vice versa, even though the truth threatens to blow everything apart. Also threatening to blow everything apart is Doug’s right-hand man, Jem (Jeremy Renner, channeling James Cagney in White Heat), who likes hurting and killing way too much. Affleck, who as a director allows his actors a large amount of freedom, has gotten fine performances across the board; the cast also includes Pete Postlethwaite as an underworld florist, Chris Cooper as Doug’s long-incarcerated father, Blake Lively as a drug-dealing tramp, and Boston rapper Slaine, who contributed songs to the soundtrack as well. The film, based on the Chuck Hogan novel Prince of Thieves, also benefits from Affleck’s genuine affection for the place where he grew up, shooting on location and setting the finale in a world-famous landmark. It’s been fascinating watching Affleck come of age in public, from his early days acting in such films as School Ties, Mall Rats, and Dazed and Confused to his wildly successful directing career, with his third film, Argo, being named Best Picture at this year’s Oscars. The Town is screening July 19 and August 5 as part of the MoMA series “A View from the Vaults: Warner Bros. Today,” consisting of thirty-one films from the last twenty years of movies coming out of the famed studio, including the Harry Potter, Dark Knight, and Lord of the Ring series as well as such wide-ranging fare as Spike Jonze’s Where the Wild Things Are, Ted Braun’s Darfur Now, Tim Burton’s Dark Shadows, Todd Phillips’s The Hangover, and Zack Snyder’s Watchmen.

Ben Affleck, who displayed great skill as a director in his debut feature, 2007’s Gone Baby Gone, did it again with his follow-up, the romantic thriller The Town. Affleck, who also cowrote the script, stars as Doug MacRay, the leader of a small group of bank robbers in tough Charlestown, Massachusetts, the bank robbery capital of America. As the film opens, the thieves are just hitting a bank and are forced to take a hostage, manager Claire Keesey (Rebecca Hall). After later letting her go unharmed, they soon realize that she lives in their neighborhood and might be able to recognize one of them, so Doug starts hanging around her, pretending to be interested in her so he can tap her for information. Meanwhile, Boston cop Dino (Titus Welliver) and FBI Special Agent Frawley (Jon Hamm) are getting closer to the gang, who continue to pull off daring heists regardless of the heat on them. Although there are a handful of plot holes you could drive an armored truck through, The Town ends up being a compelling action film and love story, with car chases, massive shootouts, and a tender relationship as Doug begins to fall for Claire, and vice versa, even though the truth threatens to blow everything apart. Also threatening to blow everything apart is Doug’s right-hand man, Jem (Jeremy Renner, channeling James Cagney in White Heat), who likes hurting and killing way too much. Affleck, who as a director allows his actors a large amount of freedom, has gotten fine performances across the board; the cast also includes Pete Postlethwaite as an underworld florist, Chris Cooper as Doug’s long-incarcerated father, Blake Lively as a drug-dealing tramp, and Boston rapper Slaine, who contributed songs to the soundtrack as well. The film, based on the Chuck Hogan novel Prince of Thieves, also benefits from Affleck’s genuine affection for the place where he grew up, shooting on location and setting the finale in a world-famous landmark. It’s been fascinating watching Affleck come of age in public, from his early days acting in such films as School Ties, Mall Rats, and Dazed and Confused to his wildly successful directing career, with his third film, Argo, being named Best Picture at this year’s Oscars. The Town is screening July 19 and August 5 as part of the MoMA series “A View from the Vaults: Warner Bros. Today,” consisting of thirty-one films from the last twenty years of movies coming out of the famed studio, including the Harry Potter, Dark Knight, and Lord of the Ring series as well as such wide-ranging fare as Spike Jonze’s Where the Wild Things Are, Ted Braun’s Darfur Now, Tim Burton’s Dark Shadows, Todd Phillips’s The Hangover, and Zack Snyder’s Watchmen.