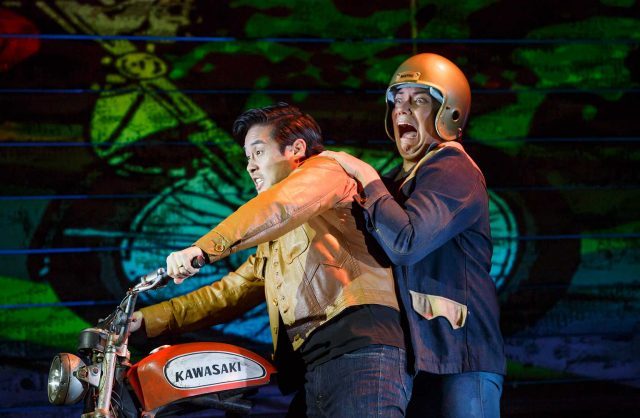

Laura Linney and Cynthia Nixon alternate roles as Regina and Birdie in MTC Broadway revival of Lillian Hellman’s The Little Foxes (photo by Joan Marcus)

Manhattan Theatre Club at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

261 West 47th St. between Broadway & Eighth Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through July 2, $89-$179

littlefoxesbroadway.com

www.manhattantheatreclub.com

Daniel Sullivan’s Broadway revival of Lillian Hellman’s 1939 drawing-room classic, The Little Foxes, is exquisitely rendered in every detail in this gorgeous Manhattan Theatre Club production, continuing through July 2 at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre. It’s an intricate tale of the business of family, and the family business, in the South in the spring of 1900, but it never feels old-fashioned or dated; instead it highlights the play’s freshness and relevance to today’s world. The conniving Hubbard clan — older brother Ben (Michael McKean), younger brother Oscar (Darren Goldstein), and sister Regina (portrayed alternately by Laura Linney and Cynthia Nixon) — are wining and dining Mr. Marshall (David Alford), a wealthy Chicago industrialist about to partner with Hubbard Sons in a cotton mill deal. “It’s very remarkable how you Southern aristocrats have kept together. Kept together and kept what belonged to you,” Mr. Marshall says. “You misunderstand, sir. Southern aristocrats have not kept together and have not kept what belonged to them,” Ben points out. “You don’t call this keeping what belongs to you?” Mr. Marshall asks, looking around the impressive room. “But we are not aristocrats. Our brother’s wife is the only one of us who belongs to the Southern aristocracy,” Ben explains, referring to Oscar’s wife, Birdie (alternately Nixon or Linney). In a classic new money/old money transaction, Oscar married the soft-spoken, timid Birdie for her bloodline and the family plantation, her beloved Lionnet. Once Lionnet and Birdie were both Hubbard property, he began beating and mistreating her, leading her to retreat into a haze of alcohol. Meanwhile, Oscar is grooming their bumbling, would-be-playboy son, Leo (Michael Benz), to join Hubbard Sons and to marry his first cousin, Alexandra (Francesca Carpanini), the teenage daughter of Regina and Horace (Richard Thomas). But to secure the deal with Mr. Marshall, Ben and Oscar need Horace, a seriously ill banker who has spent the past five months at Johns Hopkins, to contribute his share in the partnership; otherwise, they will have to bring in a stranger, something they are loathe to do. But Regina proves herself to be another shrewd Hubbard when she starts negotiating for her absent husband. Unable to execute the necessary partnership investment herself, Regina sends Alexandra to Maryland to bring back Horace, setting up an intense battle of wills over Union Pacific bonds owned by Horace, who just happens to be Leo’s boss at the bank. Watching everything unfold are the Hubbards’ servants, Addie (Caroline Stefanie Clay) and Cal (Charles Turner), who understand exactly what is going on as the post-Reconstruction South moves from its plantation slave agriculture economy to a mill-based industrial one — all the while keeping up its brutal foundation of labor exploitation. It all culminates in a spectacularly grand finale that is as wickedly funny as it is unpredictable.

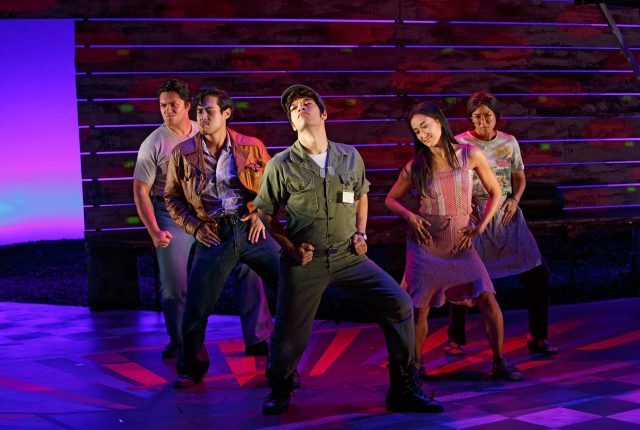

Richard Thomas, Michael McKean, Darren Goldstein, and Michael Benz discuss family business in Daniel Sullivan’s Broadway revival of Lillian Hellman classic (photo by Joan Marcus)

A magnet for big stars, The Little Foxes was first presented on Broadway in 1939, with Tallulah Bankhead as Regina and Frank Conroy as Horace. William Wyler’s Oscar-nominated 1941 film starred Bette Davis as Regina, Herbert Marshall as Horace, and Teresa Wright as Alexandra. It was previously revived on Broadway in 1967 by Mike Nichols (with Anne Bancroft, Richard A. Dysart, E. G. Marshall, and George C. Scott), in 1981 by Austin Pendleton (with Elizabeth Taylor, Maureen Stapleton, and Anthony Zerbe), and in 1997 by Jack O’Brien (with Stockard Channing, Frances Conroy, and Brian Murray). The cast for the 2017 revival is simply brilliant: McKean (All the Way, Superior Donuts) is devilishly regal as the cigar-smoking, full-bearded Ben; Goldstein (Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, Abigail’s Party) is deliciously devious as Oscar, the least well mannered of the siblings; and Thomas (Incident at Vichy, You Can’t Take It with You) is explosive as Regina’s ailing, henpecked husband who has some tricks up his sleeve. But the play’s real power lays in the roles of Regina and Birdie, two very different women, each with their own strengths and flaws, representative of both the past and the future of their gender. At Linney’s suggestion, she and Nixon alternate playing Regina and Birdie; I saw it with four-time Emmy winner, three-time Oscar nominee, and four-time Tony nominee Linney (Time Stands Still, Sight Unseen) as Regina and Tony, Grammy, and Emmy winner Nixon (Rabbit Hole, Wit) as Birdie. The two women are magical together, Linney strong and determined as the duplicitous, calculating Regina, who wants a better life for herself no matter how it impacts the others, while Nixon is delightful as the unassuming, fragile, abused Birdie, who knows more than she is letting on. Scott Pask’s set is divine, with lovely period furniture, a Hazelton Brothers piano, lush drapery, and a shadowy, ominous staircase in the back, while Jane Greenwood’s costumes are utterly transcendent, the men’s tuxes bold and impressive, the women’s dresses luxuriously elegant and revealing of their inner being. Tony winner Sullivan (Rabbit Hole, Proof) directs with impeccable attention to detail; nary the smallest matter is overlooked, and the pacing is wonderful, with two well-timed intermissions over two and a half hours. “I could wait until next week. But I can’t wait until next week,” Ben says at one point, referring to Horace’s delay in contributing his share of the investment, but he just as well could be talking to those who are still contemplating whether to see the show. “I could but I can’t. Could and can’t. Well, I must go now,” he concludes. The Little Foxes must go on July 2; don’t miss it.