John Kevin Jones pays tribute to Edgar Allan Poe at historic Merchant’s House Museum (photo by Joey Stocks)

KILLING AN EVENING WITH EDGAR ALLAN POE: MURDER AT THE MERCHANT’S HOUSE

Merchant’s House Museum

29 East Fourth St. between Lafayette St. and the Bowery

October 12-31, $18

212-777-1089

merchantshouse.org

www.summonersensemble.org

Purely by coincidence, I saw three one-man shows this week, on three successive nights, and all three have strong reasons for me to recommend them. On Tuesday, I was at the historic Merchant’s House Museum on East Fourth St. to see John Kevin Jones in Killing an Evening with Edgar Allan Poe: Murder at the Merchant’s House. Jones has a kind of cult fan club for his annual one-man version of A Christmas Carol at the museum, a home built in 1831-32 that was occupied continuously by the Tredwell family from 1835 to 1933. The nineteenth century feels very present in the house, which was one of the first twenty buildings to gain landmark status under the city’s 1965 law and functions as a museum, preserving the Tredwell family’s furnishings as they would have appeared when Poe, coincidentally, lived nearby for a time at 85 West Third St. and later in a cottage in the Bronx. Dressed in nineteenth-century-style jacket, vest, top hat, and ascot, Jones celebrates Edgar Allan Poe with three of his most popular writings, preceded by short introductions about each work and Poe’s career.

Forty people are squeezed into the Tredwells’ candlelit double parlor — with a coffin at one end and a dining table at the other — and Jones walks up and down the narrow space between, where the audience is seated on three sides, boldly delivering two classic Poe tales of treachery and murder, “The Tell-Tale Heart” and “The Cask of Amontillado,” both from memory. His deep, theatrical voice resonates through the room as he catches the eye of audience members, adding yet more chills and thrills to the mystery in the air. He then sits down with a book for the long poem “The Raven,” evoking the great Poe actor Vincent Price. Jones, director Dr. Rhonda Dodd, and stage manager Dan Renkin, the leaders of Summoners Ensemble Theatre, keep the focus on Poe’s remarkable narrative technique; you might be watching one man, but you’ll feel like you’re seeing each of Poe’s characters in vivid detail. The sold-out show continues October 22, 23, and 31; tickets for A Christmas Carol, however, are still available.

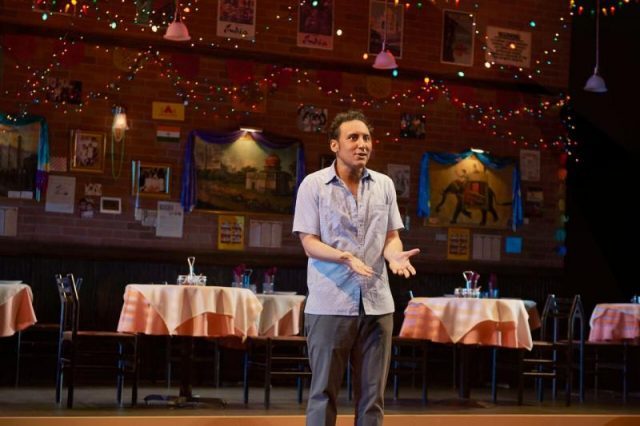

Aasif Mandvi brings back his Obie-winning Sakina’s Restaurant to the Minetta Lane (photo by Lisa Berg)

SAKINA’S RESTAURANT

Audible Theater at Minetta Lane Theatre

18 Minetta Lane between Sixth Ave. and MacDougal St.

Tuesday – Sunday through November 11, $57-$97

sakinasrestaurantplay.com

On Wednesday night I headed to the Minetta Lane Theatre, where Audible has been staging one-person shows that are also available as audios. First, Billy Crudup starred in David Cale’s modern noir Harry Clarke, then Carey Mulligan excelled in Dennis Kelly’s intense Girls & Boys, and now Aasif Mandvi has brought back his Obie-winning 1998 show, Sakina’s Restaurant. Born in India and raised in England, Mandvi studied with acting teacher Wynn Handman, whose students have also included solo specialists Eric Bogosian and John Leguizamo. In the slightly revamped autobiographical tale, directed by Kimberly Senior (Disgraced, The Niceties), Mandvi plays six characters, beginning with Agzi, an eager young man who is leaving his small, tight-knit Indian village to go to America, where he will be sponsored by Hakim (his father’s real name) and Farrida, who run Sakina’s Restaurant on, of course, East Sixth St. Before leaving, Agzi promises his mother he will write to her from all across the United States. “I will even write to you from Cleveland! Cleveland, Ma! Home of all the Indians!”

Mandvi (Disgraced, Halal in the Family) creatively slips into each character, adding glasses, a tie, a dress, or a Game Boy to delineate among Hakim, a serious man who wants only the best for his family; Farrida, who desires more out of her mundane life; their high-school-age daughter, Sakina, who has an American boyfriend and wants to immerse herself in Western culture but who has already been promised to an Indian man by their fathers; their younger son, Samir, who doesn’t really care about anything but his immediate enjoyment; Ali, Sakina’s nervous intended in the arranged marriage; and Agzi, who is not having as exciting a time as he imagined in America. Wilson Chin’s set looks just like several Sixth St. Indian restaurants I’ve been to. The story itself occasionally drags and has trouble skirting stereotypes, but Mandvi is superb, warm and likable, particularly when he talks directly to the audience as Agzi, sharing his hopes and dreams.

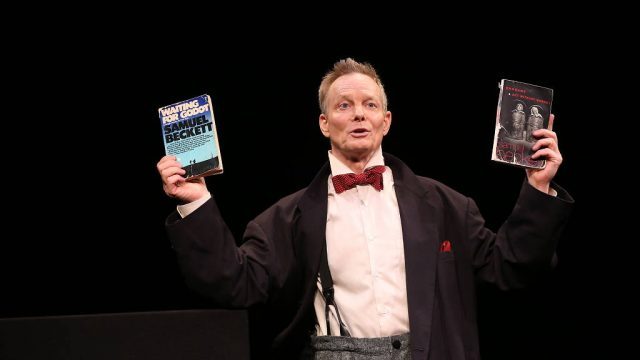

Bill Irwin shares his love of all things Samuel Beckett at the Irish Rep (photo by Carol Rosegg)

ON BECKETT

Irish Repertory Theatre

Francis J. Greenburger Mainstage

132 West 22nd St. between Sixth & Seventh Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through November 4, $50-$70

212-727-2737

irishrep.org

On Thursday night I was at the Irish Rep to see On Beckett, Bill Irwin’s very personal exploration of the work of Samuel Beckett and, in many ways, a combination of the two previous one-man shows I saw, evoking John Kevin Jones’s mastery of Edgar Allan Poe’s texts and Aasif Mandvi’s expert handling of multiple characters. For eighty-seven minutes, Tony-winning actor and certified clown Irwin delves into his vast enthusiasm for Beckett’s writings without ever becoming professorial or pedantic. “I am not a ‘Beckett scholar’ — nooo. Nor am I a Beckett biographer,” he admits. “Mine is an actor’s relationship with this language. By which I mean the deep knowledge that comes from committing words to memory, and speaking them to audiences.” Irwin (Old Hats, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?) performs selections from Beckett’s 1955 collection Texts for Nothing, his 1950s novels The Unnamable and Watt, and the Irish writer’s most famous play, Waiting for Godot, significantly altering his delivery style, voice, and rhythm for each work.

Irwin adds fascinating insight to Beckett and his oeuvre, discussing the Nobel Prize winner’s punctuation and pronoun usage, his identity and heritage, the possible influence of vaudeville on his work, his detailed stage directions, and other intricacies. “Was Beckett a writer of the body, or of the intellect?” Irwin asks. “Smells like a question you could waste a lot of time on, but I think you can say that he was a writer acutely attuned to silhouette.” His appreciation of Beckett echoes that of Jones’s for Poe, while his simple but effective costume changes — switching among numerous bowlers, putting on baggy pants and clown shoes — work like Mandvi’s to distinguish individuals. Irwin spends a significant part of the show on Waiting for Godot, discussing the correct pronunciation of the title character’s name, examining the role of Lucky, and reminiscing about the production he appeared in with Robin Williams, John Goodman, Steve Martin, and Nathan Lane. Charlie Corcoran’s spare black set consists only of a podium and two rectangular boxes that Irwin can rearrange for various purposes. Irwin is a delight to watch, his passion for Beckett infectious. He occasionally goes off topic in comic ways, wrestling with a microphone and toying with the podium, but he eventually gets back on track for an enchanting piece of theater about theater.

The following evening, my string of one-man shows came to an end with the Wheelhouse Theater’s new adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut’s Happy Birthday, Wanda June, opening Tuesday at the Duke. Bringing the theme full circle, Wanda June features a ferocious performance by Jason O’Connell, whom I saw last year in his own solo outing, The Dork Knight, about his lifelong affinity for Batman.