THE CRANES ARE FLYING (Mikhail Kalatozov, 1957)

Film Forum

209 West Houston St.

Opens Friday, July 12

212-727-8110

filmforum.org

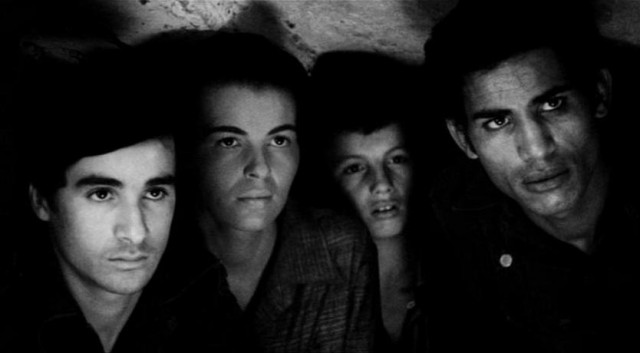

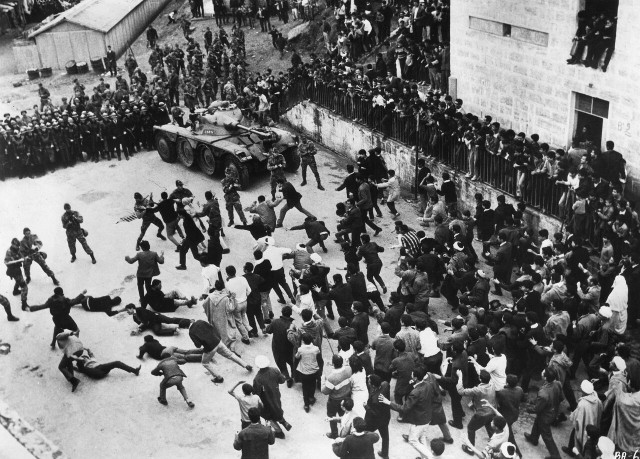

Even at a mere ninety-seven minutes, Mikhail Kalatozov’s The Cranes Are Flying, having a weeklong revival July 12-18 at Film Forum in a 2K restoration, is a sweeping Russian antiwar epic, an intimate and moving black-and-white tale of romance and betrayal during WWII. Veronika (Tatyana Samojlova) and Boris (Aleksey Batalov) are madly in love, swirling dizzyingly through the streets and up and down a winding staircase. But when Russia enters the war, Boris signs up and heads to the front, while Veronika is pursued by Boris’s cousin, Mark (Aleksandr Shvorin). Pining for word from Boris, Veronika works as a nurse at a hospital run by Boris’s father, Fyodor Ivanovich (Vasili Merkuryev), as the family, including Boris’s sister, Irina (Svetlana Kharitonova), looks askance at her relationship with Mark. The personal and political intrigue comes to a harrowing conclusion in a grand finale that for all its scale and scope gets to the very heart and soul of how the war affected the Soviet people on an individual, human level, in the family lives of women and children, lovers and cousins, husbands and wives.

Even at a mere ninety-seven minutes, Mikhail Kalatozov’s The Cranes Are Flying, having a weeklong revival July 12-18 at Film Forum in a 2K restoration, is a sweeping Russian antiwar epic, an intimate and moving black-and-white tale of romance and betrayal during WWII. Veronika (Tatyana Samojlova) and Boris (Aleksey Batalov) are madly in love, swirling dizzyingly through the streets and up and down a winding staircase. But when Russia enters the war, Boris signs up and heads to the front, while Veronika is pursued by Boris’s cousin, Mark (Aleksandr Shvorin). Pining for word from Boris, Veronika works as a nurse at a hospital run by Boris’s father, Fyodor Ivanovich (Vasili Merkuryev), as the family, including Boris’s sister, Irina (Svetlana Kharitonova), looks askance at her relationship with Mark. The personal and political intrigue comes to a harrowing conclusion in a grand finale that for all its scale and scope gets to the very heart and soul of how the war affected the Soviet people on an individual, human level, in the family lives of women and children, lovers and cousins, husbands and wives.

Unforeseen circumstances trap Veronika (Tatyana Samojlova) in wartime Russia in Mikhail Kalatozov’s masterful The Cranes Are Flying

The only Russian film to win the Palme d’Or at Cannes by itself, The Cranes Are Flying is a masterful work of art, a searing portrait of the horrors of war as seen through the eyes of one desperate woman. Adapting his own play, Viktor Rozov’s story sets up Boris and his family as a microcosm of Soviet society under Stalin; it’s no coincidence that the film was made only after the leader’s death. It’s a whirlwind piece of filmmaking, a marvelous collaboration between director Kalatozov, editor Mariya Timofeyeva (Ballad of a Soldier), composer Moisey Vaynberg (the opera The Passenger), and cinematographer Sergey Urusevsky, who also worked with Kalatozov on I Am Cuba and The Unsent Letter; Urusevsky’s camera, often handheld, is simply dazzling, whether moving through and above crowd scenes, closing in on Samojlova’s face and Batalov’s eyes, or twirling up at the sky. Poetic and lyrical, heartbreaking and maddening, The Cranes Are Flying is an exquisite example of the power of cinema.

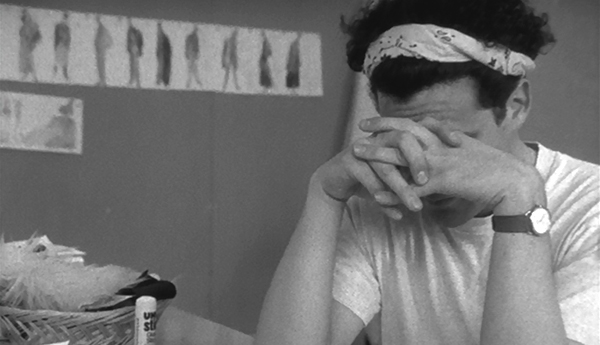

About halfway through Unzipped, Douglas Keeve’s thrilling 1995 documentary, which follows fashion designer extraordinaire Isaac Mizrahi as he puts together his fall 1994 collection following a critical disaster, Mizrahi says, “Everything’s frustrating; every single thing is frustrating. Except designing clothes. That’s not frustrating. That’s really liberating and beautiful. I don’t know, being overweight and not being able to lose weight, you know, that’s a problem. Anything you’re really working hard at and that’s not working, that’s a problem. But frankly, designing clothes is never a problem.” Of course, the statement doesn’t exactly ring true as Mizrahi, usually with his trademark bandanna wound around his wild, curly hair, encounters his fair share of difficulties as he meets with Candy Pratts and André Leon Talley from Vogue and Polly Mellen from Allure, expresses his hopes and fears with Mark Morris, Sandra Bernhard, Eartha Kitt, and his mother, and works with such supermodels as Kate Moss, Naomi Campbell, Cindy Crawford, Shalom Harlow, Linda Evangelista, Carla Bruni, Christy Turlington, and Amber Valletta. Along the way he makes endless pop-culture references, singing the theme song from The Mary Tyler Moore Show, citing scenes from The Red Shoes, Marnie, Valley of the Dolls, and Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? and using Nanook of the North and The Call of the Wild as creative inspiration.

About halfway through Unzipped, Douglas Keeve’s thrilling 1995 documentary, which follows fashion designer extraordinaire Isaac Mizrahi as he puts together his fall 1994 collection following a critical disaster, Mizrahi says, “Everything’s frustrating; every single thing is frustrating. Except designing clothes. That’s not frustrating. That’s really liberating and beautiful. I don’t know, being overweight and not being able to lose weight, you know, that’s a problem. Anything you’re really working hard at and that’s not working, that’s a problem. But frankly, designing clothes is never a problem.” Of course, the statement doesn’t exactly ring true as Mizrahi, usually with his trademark bandanna wound around his wild, curly hair, encounters his fair share of difficulties as he meets with Candy Pratts and André Leon Talley from Vogue and Polly Mellen from Allure, expresses his hopes and fears with Mark Morris, Sandra Bernhard, Eartha Kitt, and his mother, and works with such supermodels as Kate Moss, Naomi Campbell, Cindy Crawford, Shalom Harlow, Linda Evangelista, Carla Bruni, Christy Turlington, and Amber Valletta. Along the way he makes endless pop-culture references, singing the theme song from The Mary Tyler Moore Show, citing scenes from The Red Shoes, Marnie, Valley of the Dolls, and Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? and using Nanook of the North and The Call of the Wild as creative inspiration.