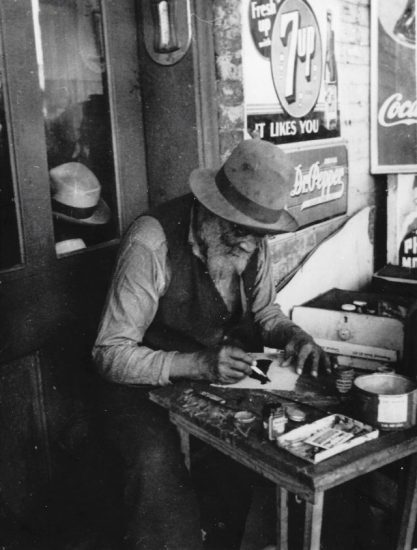

Sun Ra is one of the free jazz pioneers featured in Fire Music (photo by Baron Wolman / courtesy of Submarine Deluxe)

FIRE MUSIC: THE STORY OF FREE JAZZ (Tom Surgal, 2018)

Film Forum

209 West Houston St.

Opens Friday, September 10

212-727-8110

filmforum.org

www.firemusic.org

College is supposed to be a life-changing, career-defining experience. For me, there were two specific seminal moments, both of which took place in the classroom: discovering avant-garde film in a course taught by New York Film Festival cofounder Amos Vogel, author of Film as a Subversive Art, and being introduced to the free jazz movement, the radical response to bebop, in the History of American Music. Without those two flashpoints, it’s unlikely I would be writing a review of Tom Surgal’s Fire Music: The Story of Free Jazz all these years later.

Opening on September 10 at Film Forum, Fire Music takes a deep dive into free jazz, told with spectacular archival footage and old and new interviews with more than three dozen musicians who were part of the sonic upheaval, with famed jazz writer Gary Giddins adding further insight. Writer-director Surgal, who is also a drummer and percussionist, traces the development of free jazz chronologically, focusing on such groundbreaking figures as saxophonists Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy, John Coltrane, Albert Ayler, and Sam Rivers, pianist Cecil Taylor, and keyboardist and synth maestro Sun Ra. “It was terrifying for people,” Giddins says about the original reaction to free jazz, from audiences and musicians. “A lot of people were just, What the hell is this? This isn’t even music.”

There are snippets of live performances by Charlie Parker, Sun Ra Arkestra, Dolphy, Coltrane, Ayler, Max Roach, Don Cherry, Marion Brown, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, M’Boom, the Sam Rivers Trio, Globe Unity Orchestra, and others that set the right mood; this is not swing or bop but something wholly different — and dissonant — that requires an open mind and open ears, but it’s pure magic. “It was like a religion,” pianist Carla Bley remembers. Saxophonist John Tchicai explains, “Each individual could play in his own tempo or create melodies that were independent, in a way, from what the other players were playing. We had to break some boundary to be able to create something new.”

Surgal talks to the musicians about improvising without following standard chord progressions, the four-day October Revolution at the Cellar Café, trumpeter Bill Dixon starting the Jazz Composers’ Guild, pianist Muhal Richard Abrams cofounding the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians in Chicago, the formation of the Black Artists Group in St. Louis, the loft scene in New York City, the development of free jazz in New York, Los Angeles, the Midwest, and Europe, and the importance of the 1960 record Free Jazz by the Ornette Coleman Double Quartet, featuring Coleman, Cherry, Scott LaFaro, and Billy Higgins on the left channel and Dolphy, Freddie Hubbard, Charlie Haden, and Ed Blackwell on the right. Sadly, sixteen of the artists in the film have passed away since Surgal started the project; many others seen in clips died at an early age.

For these players, it was more than just fame and fortune; they were constantly called upon to defend free jazz itself. Taylor, who came out of the New England Conservatory, explains, “It seems to me what music is is everything that you do.” Pianist Misha Engelberg admits, “I am a complete fraud.” Meanwhile, Coleman trumpeter Bobby Bradford says of Ayler, “Here’s a saxophone player, man, that we all are thinking, we just broke the sound barrier — wow — and here’s a guy that’s gonna take us to another planet. Is that what we want to do?” As far as outer space is concerned, Sun Ra claims to be from Saturn.

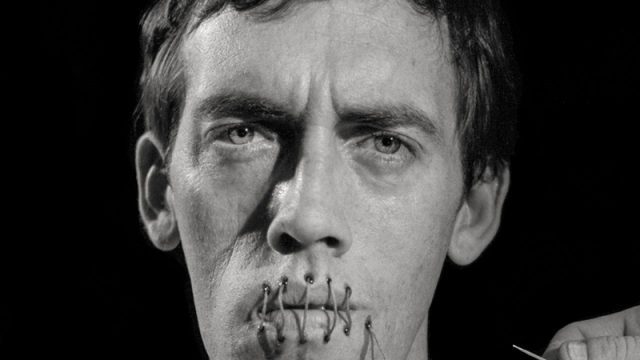

John Coltrane is highlighted as the spiritual father of the free jazz movement (photo by Lee Tanner / courtesy of Submarine Deluxe)

Among the others who chime in are saxophonists Gato Barbieri, John Gilmore, Marshall Allen, Anthony Braxton, Oliver Lake, Noah Howard, Prince Lasha, and Archie Shepp, trombonists Roswell Rudd and George Lewis, trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith, pianists Burton Greene and Dave Burrell, drummers Rashied Ali, Barry Altschul, Thurman Barker, Warren Smith, Han Bennink, and Günter “Baby” Sommer, and vibesmen Karl Berger and Gunter Hampel, each musician unique and cooler than cool as great clips and stories move and groove to their own offbeat, subversive cacophony, brought together in a furious improvisation by editor and cowriter John Northrop, with original music by Lin Culbertson. Producers on the film include such contemporary musicians as Thurston Moore, Nels Cline, and Jeff Tweedy.

Surgal made Fire Music because he felt that the free jazz movement is largely forgotten today; his documentary goes a long way in showing how shortsighted that is. You don’t have to be in college to love this incredible music, and the film itself, which is a crash course in an unforgettable sound like no other.

(Film Forum will host an in-person Q&A with Surgal, Moore, and Smith at the 7:00 show on September 10 and with Surgal, Barker, and jazz writer Clifford Allen at the 7:00 screening on September 11.)