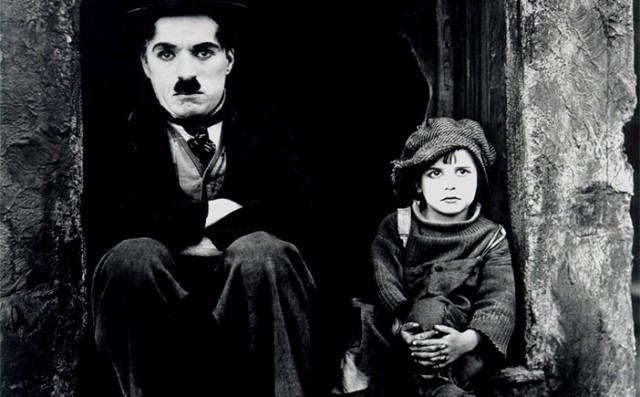

THE KID (Charles Chaplin, 1921)

Film Forum

209 West Houston St.

Wednesday, January 1, 1:00

Series runs January 1-7

212-727-8110

www.filmforum.org

Nearly one hundred years ago, in February 1914, Charlie Chaplin debuted one of cinema’s most endearing characters, the Tramp, in the Keystone shorts Kid Auto Races at Venice and Mabel’s Strange Predicament. Film Forum is paying tribute to the waddling, mustachioed vagrant with a weeklong festival highlighted by a New Year’s Day marathon of six of Chaplin’s best. The all-day party begins, appropriately enough, with Chaplin’s first feature, The Kid, which was a breakthrough for the British-born silent-film star, a touching and tender sixty-eight-minute triumph about a poor soul getting a second chance at life. When a baby arrives at his doorstep, a Tramp (Chaplin) first tries to ditch the boy, but he ends up taking him to his ramshackle apartment and raising him as if he were his own flesh and blood. Although he has so little, the Tramp makes sure the child, eventually played by Jackie Coogan, has food to eat, clothes to wear, and books to read. Meanwhile, the mother (Edna Purviance, Chaplin’s former lover), who has become a big star, regrets her earlier decision and wonders where her son is, setting up a heartbreaking finale. In addition to playing the starring role, Chaplin wrote, produced, directed, and edited the film and composed the score for his company, First National, wonderfully blending slapstick comedy, including a hysterical street fight with an angry neighbor, with touching melodrama as he examines poverty in post-WWI America, especially as seen through the eyes of the orphan boy, played beautifully by Coogan, who went on to marry Betty Grable, among others, and star as Uncle Fester in The Addams Family. Chaplin’s innate ability to tell a moving story primarily through images reveals his understanding of cinema’s possibilities, and The Kid holds up as one of his finest, alongside such other silent classics as 1925’s The Gold Rush and 1931’s City Lights. The film will be preceded by the 1919 short A Day’s Pleasure, in which Chaplin and Purviance play Coogan’s parents. The double feature is also screening January 5 at 5:20.

Nearly one hundred years ago, in February 1914, Charlie Chaplin debuted one of cinema’s most endearing characters, the Tramp, in the Keystone shorts Kid Auto Races at Venice and Mabel’s Strange Predicament. Film Forum is paying tribute to the waddling, mustachioed vagrant with a weeklong festival highlighted by a New Year’s Day marathon of six of Chaplin’s best. The all-day party begins, appropriately enough, with Chaplin’s first feature, The Kid, which was a breakthrough for the British-born silent-film star, a touching and tender sixty-eight-minute triumph about a poor soul getting a second chance at life. When a baby arrives at his doorstep, a Tramp (Chaplin) first tries to ditch the boy, but he ends up taking him to his ramshackle apartment and raising him as if he were his own flesh and blood. Although he has so little, the Tramp makes sure the child, eventually played by Jackie Coogan, has food to eat, clothes to wear, and books to read. Meanwhile, the mother (Edna Purviance, Chaplin’s former lover), who has become a big star, regrets her earlier decision and wonders where her son is, setting up a heartbreaking finale. In addition to playing the starring role, Chaplin wrote, produced, directed, and edited the film and composed the score for his company, First National, wonderfully blending slapstick comedy, including a hysterical street fight with an angry neighbor, with touching melodrama as he examines poverty in post-WWI America, especially as seen through the eyes of the orphan boy, played beautifully by Coogan, who went on to marry Betty Grable, among others, and star as Uncle Fester in The Addams Family. Chaplin’s innate ability to tell a moving story primarily through images reveals his understanding of cinema’s possibilities, and The Kid holds up as one of his finest, alongside such other silent classics as 1925’s The Gold Rush and 1931’s City Lights. The film will be preceded by the 1919 short A Day’s Pleasure, in which Chaplin and Purviance play Coogan’s parents. The double feature is also screening January 5 at 5:20.

THE GOLD RUSH (Charles Chaplin, 1925)

Wednesday, January 1, 2:30

www.filmforum.org

Film Forum’s Charlie Chaplin marathon continues with the recently restored 35mm print of the complete version of The Gold Rush, with a newly recorded orchestral score. Made four years prior to the Great Depression, the slapstick comedy, which Chaplin called “the picture I want to be remembered by,” is still remarkably socially relevant, tackling unemployment, crime, hunger, and poverty. Chaplin, who wrote, produced, and directed the silent masterpiece, stars as the Lone Prospector, a little tramp who has set out to strike it rich during the Alaskan Gold Rush of 1848 but isn’t really having much luck. He takes shelter during a snowstorm in a small shack, does battle with a pair of much bigger men, turns into a chicken, and, yes, eats his shoe, doing whatever it takes to survive. The prescient film was originally to star Lita Grey as the love interest, but Chaplin impregnated (and later married) the sixteen-year-old, so she was replaced by Georgia Hale. The cast also features Mack Swain as Big Jim McKay, Malcolm Waite as ladies’ man Jack Cameron, and Tom Murray as Black Larsen. (And by the way, if you’ve only seen Chaplin’s reedited 1942 version with his own treacly narration and score, well, you’ve never really experienced this American treasure.) The Gold Rush is also screening New Year’s Eve at 7:00 and on January 5 & 6.

Film Forum’s Charlie Chaplin marathon continues with the recently restored 35mm print of the complete version of The Gold Rush, with a newly recorded orchestral score. Made four years prior to the Great Depression, the slapstick comedy, which Chaplin called “the picture I want to be remembered by,” is still remarkably socially relevant, tackling unemployment, crime, hunger, and poverty. Chaplin, who wrote, produced, and directed the silent masterpiece, stars as the Lone Prospector, a little tramp who has set out to strike it rich during the Alaskan Gold Rush of 1848 but isn’t really having much luck. He takes shelter during a snowstorm in a small shack, does battle with a pair of much bigger men, turns into a chicken, and, yes, eats his shoe, doing whatever it takes to survive. The prescient film was originally to star Lita Grey as the love interest, but Chaplin impregnated (and later married) the sixteen-year-old, so she was replaced by Georgia Hale. The cast also features Mack Swain as Big Jim McKay, Malcolm Waite as ladies’ man Jack Cameron, and Tom Murray as Black Larsen. (And by the way, if you’ve only seen Chaplin’s reedited 1942 version with his own treacly narration and score, well, you’ve never really experienced this American treasure.) The Gold Rush is also screening New Year’s Eve at 7:00 and on January 5 & 6.

CITY LIGHTS (Charles Chaplin, 1931)

Wednesday, January 1, 5:30

www.filmforum.org

Another genuine American treasure, City Lights is one of Chaplin’s most thoroughly entertaining masterpieces. Serving as writer, director, editor, producer, and composer, Chaplin also stars as the Little Tramp, a destitute man who instantly falls in love upon seeing a blind Flower Girl (Virginia Cherrill). When she mistakes him for a millionaire with a fancy car, he decides to pretend to be rich so she might like him, but when he actually becomes pals with the business tycoon (Harry Myers), he thinks he might eventually be able to get the money for her to get a new operation that could restore her eyesight. The only problem is that the millionaire, who parties wildly with the Little Tramp every evening, taking him to ritzy nightclubs and even giving him his car at one point, remembers nothing the next morning and doesn’t want anything to do with him. It all leads to an unforgettable conclusion that pulls at the heartstrings. Despite the availability of sound, Chaplin chose to make City Lights a silent picture, although he did incorporate sound effects and, in one section, distorted speech. Although the film features several hysterical slapstick bits, including the opening, when the Little Tramp is sleeping on a statue entitled “Peace and Prosperity” as it is unveiled, and a scene in which he saves the millionaire from a suicide attempt, virtually every minute comments on the social reality of depression-era America and the widening gap between the rich and the poor. Metaphors abound as the Little Tramp tries his best to maintain a smile and search out love during the bleakest of times. The film will also be shown four times on January 4.

Another genuine American treasure, City Lights is one of Chaplin’s most thoroughly entertaining masterpieces. Serving as writer, director, editor, producer, and composer, Chaplin also stars as the Little Tramp, a destitute man who instantly falls in love upon seeing a blind Flower Girl (Virginia Cherrill). When she mistakes him for a millionaire with a fancy car, he decides to pretend to be rich so she might like him, but when he actually becomes pals with the business tycoon (Harry Myers), he thinks he might eventually be able to get the money for her to get a new operation that could restore her eyesight. The only problem is that the millionaire, who parties wildly with the Little Tramp every evening, taking him to ritzy nightclubs and even giving him his car at one point, remembers nothing the next morning and doesn’t want anything to do with him. It all leads to an unforgettable conclusion that pulls at the heartstrings. Despite the availability of sound, Chaplin chose to make City Lights a silent picture, although he did incorporate sound effects and, in one section, distorted speech. Although the film features several hysterical slapstick bits, including the opening, when the Little Tramp is sleeping on a statue entitled “Peace and Prosperity” as it is unveiled, and a scene in which he saves the millionaire from a suicide attempt, virtually every minute comments on the social reality of depression-era America and the widening gap between the rich and the poor. Metaphors abound as the Little Tramp tries his best to maintain a smile and search out love during the bleakest of times. The film will also be shown four times on January 4.

MODERN TIMES (Charles Chaplin, 1936)

Wednesday, January 1, 7:20

www.filmforum.org

As America slowly recovered from the Great Depression and headed toward the Second World War, Charlie Chaplin also found himself trapped between the past and the future. Talkies had started in 1927 with Al Jolson in The Jazz Singer, but the British-born actor, writer, director, producer, and composer had not crossed over yet, still favoring the silent cinema that had made him an international star. But his 1936 masterpiece, Modern Times, tackled the coming of the modern era in myriad ways, both public and personal, in the world at large as well as in cinema itself. Chaplin stars as an assembly line worker who literally gets caught up in the cogs of machinery, suffers a nervous breakdown, gets sent to prison for leading a Communist march he was not a part of, accidentally dabbles in a little nose candy, and falls in love with a homeless gamin who lives by her wits on the docks, played by his real-life lover, Paulette Goddard. He tries to fit in to the ever-changing society, without much luck; he even has trouble getting himself arrested again, thinking that jail is a better option than what’s out there. The unemployed former factory worker and the gamin move into a run-down shack and try to pretend that they are a happy, successful married couple, but the harsh reality of their poor existence continually thwarts them. Modern Times is a brutally funny, honest, and insightful examination of the socioeconomic conditions of America in the 1930s. As corporations began to grow, workers became nameless automatons; in fact, neither of the film’s protagonists is given a name. For the first time, Chaplin uses sound, but always in ingenious ways: the factory owner, who watches his workers like a hawk, using surveillance cameras that are remarkably prescient, talks only via a screen as he yells at his employees; music, which Chaplin previously utilized only on the backing soundtrack, now comes from bands seen on camera, as if they’re playing live; and the Little Tramp himself gets into the act as a singing waiter, although it’s not exactly like Garbo breaking her on-screen silence. Chaplin’s choice to include some sound while still avoiding even a single strand of actual dialogue between characters is a brash commentary on the technological revolution that was taking hold of the country and, of course, impacting the film industry. Chaplin’s previous movie, the 1931 classic City Lights, was a more traditional silent film, but with his next work, 1940’s The Great Dictator, he finally made the transition to a full talkie, albeit still finding himself trapped between two worlds, playing both a poor ghetto barber and the Fascist Hitler-like leader of Tomania. Modern Times can also be seen four times on January 3.

As America slowly recovered from the Great Depression and headed toward the Second World War, Charlie Chaplin also found himself trapped between the past and the future. Talkies had started in 1927 with Al Jolson in The Jazz Singer, but the British-born actor, writer, director, producer, and composer had not crossed over yet, still favoring the silent cinema that had made him an international star. But his 1936 masterpiece, Modern Times, tackled the coming of the modern era in myriad ways, both public and personal, in the world at large as well as in cinema itself. Chaplin stars as an assembly line worker who literally gets caught up in the cogs of machinery, suffers a nervous breakdown, gets sent to prison for leading a Communist march he was not a part of, accidentally dabbles in a little nose candy, and falls in love with a homeless gamin who lives by her wits on the docks, played by his real-life lover, Paulette Goddard. He tries to fit in to the ever-changing society, without much luck; he even has trouble getting himself arrested again, thinking that jail is a better option than what’s out there. The unemployed former factory worker and the gamin move into a run-down shack and try to pretend that they are a happy, successful married couple, but the harsh reality of their poor existence continually thwarts them. Modern Times is a brutally funny, honest, and insightful examination of the socioeconomic conditions of America in the 1930s. As corporations began to grow, workers became nameless automatons; in fact, neither of the film’s protagonists is given a name. For the first time, Chaplin uses sound, but always in ingenious ways: the factory owner, who watches his workers like a hawk, using surveillance cameras that are remarkably prescient, talks only via a screen as he yells at his employees; music, which Chaplin previously utilized only on the backing soundtrack, now comes from bands seen on camera, as if they’re playing live; and the Little Tramp himself gets into the act as a singing waiter, although it’s not exactly like Garbo breaking her on-screen silence. Chaplin’s choice to include some sound while still avoiding even a single strand of actual dialogue between characters is a brash commentary on the technological revolution that was taking hold of the country and, of course, impacting the film industry. Chaplin’s previous movie, the 1931 classic City Lights, was a more traditional silent film, but with his next work, 1940’s The Great Dictator, he finally made the transition to a full talkie, albeit still finding himself trapped between two worlds, playing both a poor ghetto barber and the Fascist Hitler-like leader of Tomania. Modern Times can also be seen four times on January 3.

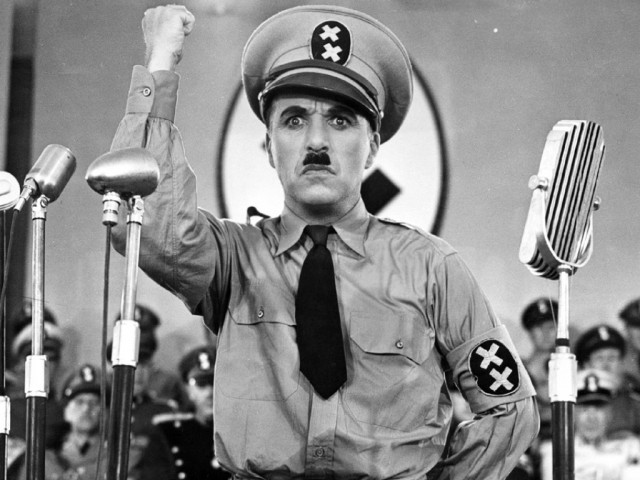

Paulette Goddard and Charlie Chaplin take on the Third Reich in his first talkie, THE GREAT DICTATOR

THE GREAT DICTATOR (Charles Chaplin, 1940)

Wednesday, January 1, 9:10

www.filmforum.org

Learning of many of the horrible things the Third Reich was doing, Charlie Chaplin could not hold his tongue anymore, finally making his first talking picture in 1940. In The Great Dictator, writer-director-producer Chaplin unrelentingly mocks Adolf Hitler and the rise of the Nazis in Germany, albeit with a very serious edge, as WWII threatens. Chaplin plays the dual roles of a simple Jewish barber living in the ghetto (who has elements of the Little Tramp) and Adenoid Hinkle, the rather Hitler-esque Fascist leader of the country of Tomania. Just as he named the nation after a food-borne illness (ptomaine poisoning), Chaplin does not go for subtlety in the film; his right-hand man is Herr Garbitsch (Henry Daniel spoofing Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels), and his military mastermind is Field Marshal Herring (Billy Gilbert making fun of Heinrich Himmler). Chaplin plays Hinkle like a cartoon character, with pratfalls galore, and when he speaks in German, especially when he gives a major speech, he spits out fake German words with a smattering of funny English ones. When he learns that Benzino Napaloni (Jack Oakie as a melding of Benito Mussolini and Napoleon Bonaparte) has gathered his troops on the Osterlitz border (think Anschluss), Hinkle invites the Bacteria dictator to his Tomanian palace, where they engage in numerous hysterical bouts of one-upmanship, including a riotous battle involving barber chairs. Meanwhile, Chaplin performs another of the film’s most memorable scenes, the shave of an old man set to Brahms’s “Hungarian Dance No. 5.” But when Commander Schultz (Reginald Gardiner) leaves the Nazi regime and decides to help the Jewish people in the ghetto, Hinkle sends his stormtroopers out to find the traitor, leading to a major case of mistaken identity and a heartfelt, if overly melodramatic, finale. Chaplin’s lover at the time, Paulette Goddard, plays Hannah (named for Chaplin’s mother), a young Jewish woman living in the ghetto, and Bowery Boys fans will recognize Bernard Gorcey, who played sweet-shop owner Louie Dombrowski in the goofy film series, as Mr. Mann.

Learning of many of the horrible things the Third Reich was doing, Charlie Chaplin could not hold his tongue anymore, finally making his first talking picture in 1940. In The Great Dictator, writer-director-producer Chaplin unrelentingly mocks Adolf Hitler and the rise of the Nazis in Germany, albeit with a very serious edge, as WWII threatens. Chaplin plays the dual roles of a simple Jewish barber living in the ghetto (who has elements of the Little Tramp) and Adenoid Hinkle, the rather Hitler-esque Fascist leader of the country of Tomania. Just as he named the nation after a food-borne illness (ptomaine poisoning), Chaplin does not go for subtlety in the film; his right-hand man is Herr Garbitsch (Henry Daniel spoofing Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels), and his military mastermind is Field Marshal Herring (Billy Gilbert making fun of Heinrich Himmler). Chaplin plays Hinkle like a cartoon character, with pratfalls galore, and when he speaks in German, especially when he gives a major speech, he spits out fake German words with a smattering of funny English ones. When he learns that Benzino Napaloni (Jack Oakie as a melding of Benito Mussolini and Napoleon Bonaparte) has gathered his troops on the Osterlitz border (think Anschluss), Hinkle invites the Bacteria dictator to his Tomanian palace, where they engage in numerous hysterical bouts of one-upmanship, including a riotous battle involving barber chairs. Meanwhile, Chaplin performs another of the film’s most memorable scenes, the shave of an old man set to Brahms’s “Hungarian Dance No. 5.” But when Commander Schultz (Reginald Gardiner) leaves the Nazi regime and decides to help the Jewish people in the ghetto, Hinkle sends his stormtroopers out to find the traitor, leading to a major case of mistaken identity and a heartfelt, if overly melodramatic, finale. Chaplin’s lover at the time, Paulette Goddard, plays Hannah (named for Chaplin’s mother), a young Jewish woman living in the ghetto, and Bowery Boys fans will recognize Bernard Gorcey, who played sweet-shop owner Louie Dombrowski in the goofy film series, as Mr. Mann.

A seminal achievement that was supposedly seen by Hitler twice, The Great Dictator is filled with marvelous moments, from Hinkle dancing with a balloon globe to several of the Jews in the ghetto trying to hide in the same chest, but the film does suffer from pedagoguery in making its political points, and some of the slapstick is too lowbrow. Nominated for five Oscars, it falls somewhere between the Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup (1933) and the Three Stooges’ You Nazty Spy! (1940) while also referencing the 1921 silent film King, Queen, Joker, in which Chaplin’s older half-brother, Sidney (who also directed), played the dual role of a modest barber and the king of the fictional Coronia. The Great Dictator is also screening twice on January 5. The series continues through January 7 with The Circus (including 4:00 on New Year’s Day), six shorts programs divided into Chaplin’s days at First National, Essanay, Mutual, and Keystone, and Kevin Brownlow and David Gill’s 1983 documentary, Unknown Chaplin.

In 2003, Amsterdam’s crown jewel, the Rijksmuseum, was closed to begin a major renovation. Little did everyone know at the time that the project would be delayed for years and go hundreds of millions of dollars over budget. Dutch director Oeke Hoogendijk captures all the surprisingly gripping fun and intrigue in the two-part, four-hour documentary The New Rijksmuseum. Hoogendijk brings her camera into every architectural meeting, monetary debate, and contractor dilemma, gaining remarkable access as no one shies away from sharing their personal and professional feelings on everything from the heated battle with community cycling activists over public use of the building’s entrance as a bike passage to such exacting details as paint color, smoothness of the walls, the art-historical value of certain works, and staying true to Pierre Cuypers’s 1885 building. The first documentary follows museum director Ronald de Leeuw as the process gets under way and continually gets mired in such issues as bidding contests that end up having only one participating company and the city’s dislike for a modern study center addition. In the second film, Wim Pijbes takes over as museum director in 2008, and his problems quickly mount as well as construction work eventually starts and deadlines approach. “I spend more time on cyclists than Rembrandt,” he acknowledges. “It’s my fate.” The interplay among such architects as Antonio Cruz, Antonio Ortiz, and Jean-Michel Wilmotte, a succession of project managers, curators of individual museum galleries, and the director is simply fascinating as they all give their very frank opinions on the renovation of the home of such treasures as Rembrandt’s “The Night Watch” and Vermeer’s “The Milkmaid.” There’s also a whole lot of hysterical eye rolling. Hoogendijk’s two films are part mystery, part thriller, part absurdist comedy, but at the heart of it all is a deep love of art and the understanding of its cultural importance. “You gain all this knowledge only to forget it all again, but the essence remains with you,” says Asian Pavilion curator Menno Fitski. “You don’t have to remember everything you see in a museum. The experience is what makes you feel like a better human being.” The New Rijksmuseum will change the way you experience museums, especially the next time you walk through MoMA, the Met, the Louvre, or any other major cultural institution, and perhaps most of all, it will make you want to go to Amsterdam and see the new Rijksmuseum itself. The two parts are being shown at Film Forum through January 1; although you can see them separately for the price of one admission, it’s a lot more exciting watching them back to back, immersing yourself in this crazy, complicated love story.

In 2003, Amsterdam’s crown jewel, the Rijksmuseum, was closed to begin a major renovation. Little did everyone know at the time that the project would be delayed for years and go hundreds of millions of dollars over budget. Dutch director Oeke Hoogendijk captures all the surprisingly gripping fun and intrigue in the two-part, four-hour documentary The New Rijksmuseum. Hoogendijk brings her camera into every architectural meeting, monetary debate, and contractor dilemma, gaining remarkable access as no one shies away from sharing their personal and professional feelings on everything from the heated battle with community cycling activists over public use of the building’s entrance as a bike passage to such exacting details as paint color, smoothness of the walls, the art-historical value of certain works, and staying true to Pierre Cuypers’s 1885 building. The first documentary follows museum director Ronald de Leeuw as the process gets under way and continually gets mired in such issues as bidding contests that end up having only one participating company and the city’s dislike for a modern study center addition. In the second film, Wim Pijbes takes over as museum director in 2008, and his problems quickly mount as well as construction work eventually starts and deadlines approach. “I spend more time on cyclists than Rembrandt,” he acknowledges. “It’s my fate.” The interplay among such architects as Antonio Cruz, Antonio Ortiz, and Jean-Michel Wilmotte, a succession of project managers, curators of individual museum galleries, and the director is simply fascinating as they all give their very frank opinions on the renovation of the home of such treasures as Rembrandt’s “The Night Watch” and Vermeer’s “The Milkmaid.” There’s also a whole lot of hysterical eye rolling. Hoogendijk’s two films are part mystery, part thriller, part absurdist comedy, but at the heart of it all is a deep love of art and the understanding of its cultural importance. “You gain all this knowledge only to forget it all again, but the essence remains with you,” says Asian Pavilion curator Menno Fitski. “You don’t have to remember everything you see in a museum. The experience is what makes you feel like a better human being.” The New Rijksmuseum will change the way you experience museums, especially the next time you walk through MoMA, the Met, the Louvre, or any other major cultural institution, and perhaps most of all, it will make you want to go to Amsterdam and see the new Rijksmuseum itself. The two parts are being shown at Film Forum through January 1; although you can see them separately for the price of one admission, it’s a lot more exciting watching them back to back, immersing yourself in this crazy, complicated love story.

William A. Wellman’s rarely screened 1931 doozy, Night Nurse, is the first of five collaborations between Wellman and Barbara Stanwyck. Based on Dora Macy’s 1930 novel, Night Nurse stars Stanwyck as Lora Hart, a young woman determined to become a nurse. She gets a probationary job at a city hospital, where she is taken under the wing of Maloney (Joan Blondell), who likes to break the rules and torture the head nurse, the stodgy Miss Dillon (Vera Lewis). Shortly after treating a bootlegger (Ben Lyon) for a gunshot wound and agreeing not to report it to the police, Lora starts working for a shady doctor (Ralf Harolde) taking care of two sick children (Marcia Mae Jones and Betty Jane Graham) whose proudly dipsomaniac mother (Charlotte Merriam) is being manipulated by her suspicious chauffeur (Clark Gable). Wellman pulls out all the stops, hinting at or simply depicting murder, child endangerment, rape, alcoholism, lesbianism, physical brutality, and Blondell and Stanwyck regularly frolicking around in their undergarments. It’s as if Wellman is thumbing his nose directly at the soon-to-be-in-place Hays Code in scene after scene. Although far from his best film — Wellman directed such classics as Wings (1927), The Public Enemy (1931), A Star Is Born (1937), Nothing Sacred (1937), Beau Geste (1939), and The Ox-Bow Incident (1943) — Night Nurse is an overly melodramatic, dated, but entertaining little tale with quite a surprise ending. Night Nurse is screening twice on December 8 as part of Film Forum’s epic “Stanwyck” series and will be shown in a double feature with the uncensored, dastardly sordid version of Alfred E. Green’s 1933 Baby Face, in which Stanwyck plays a woman who was pimped out by her father in her early teens and now knows how to use her body to get exactly what she wants. The festival is being held in conjunction with the first major biography of the glamorous star, Victoria Wilson’s A Life of Barbara Stanwyck: Steel-True 1907-1940; Wilson will be introducing several films over the course of the series, which runs December 6-31, and will give the illustrated talk “Stanwyck Before Hollywood” on December 8 at 3:30 before the screening of Baby Face.

William A. Wellman’s rarely screened 1931 doozy, Night Nurse, is the first of five collaborations between Wellman and Barbara Stanwyck. Based on Dora Macy’s 1930 novel, Night Nurse stars Stanwyck as Lora Hart, a young woman determined to become a nurse. She gets a probationary job at a city hospital, where she is taken under the wing of Maloney (Joan Blondell), who likes to break the rules and torture the head nurse, the stodgy Miss Dillon (Vera Lewis). Shortly after treating a bootlegger (Ben Lyon) for a gunshot wound and agreeing not to report it to the police, Lora starts working for a shady doctor (Ralf Harolde) taking care of two sick children (Marcia Mae Jones and Betty Jane Graham) whose proudly dipsomaniac mother (Charlotte Merriam) is being manipulated by her suspicious chauffeur (Clark Gable). Wellman pulls out all the stops, hinting at or simply depicting murder, child endangerment, rape, alcoholism, lesbianism, physical brutality, and Blondell and Stanwyck regularly frolicking around in their undergarments. It’s as if Wellman is thumbing his nose directly at the soon-to-be-in-place Hays Code in scene after scene. Although far from his best film — Wellman directed such classics as Wings (1927), The Public Enemy (1931), A Star Is Born (1937), Nothing Sacred (1937), Beau Geste (1939), and The Ox-Bow Incident (1943) — Night Nurse is an overly melodramatic, dated, but entertaining little tale with quite a surprise ending. Night Nurse is screening twice on December 8 as part of Film Forum’s epic “Stanwyck” series and will be shown in a double feature with the uncensored, dastardly sordid version of Alfred E. Green’s 1933 Baby Face, in which Stanwyck plays a woman who was pimped out by her father in her early teens and now knows how to use her body to get exactly what she wants. The festival is being held in conjunction with the first major biography of the glamorous star, Victoria Wilson’s A Life of Barbara Stanwyck: Steel-True 1907-1940; Wilson will be introducing several films over the course of the series, which runs December 6-31, and will give the illustrated talk “Stanwyck Before Hollywood” on December 8 at 3:30 before the screening of Baby Face.

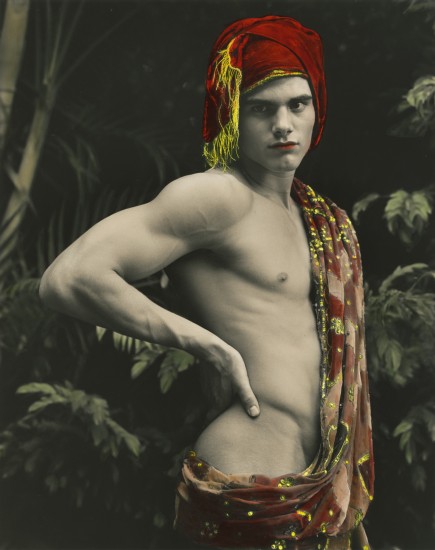

Fashion photographer Bruce Weber, who directed the seminal Chet Baker doc Let’s Get Lost a quarter century ago, made this fun hodgepodge of still photos, old color and black-and-white footage, and new interviews and voice-over narration back in 2001. You might not know much about Frances Faye, but after seeing her perform in vintage Ed Sullivan clips and listening to her manager/longtime partner discuss their life together, you’ll be searching YouTube to check out a lot more. The film also examines how Weber selects and treats his male models, who are often shot in homoerotic poses for major designers (and later go on to get married and have children). As a special treat, Jan-Michael Vincent’s extensive full-frontal nude scene in Daniel Petrie and Sidney Sheldon’s 1974 Buster and Billie is on display here, as are vintage clips of Sammy Davis Jr., adventurer Sir Wilfred Thesiger, former Vogue editor Diana Vreeland, and Robert Mitchum singing in a recording studio with Dr. John. The film is about model Peter Johnson and Weber as much as it is about the cult of celebrity; Weber gets to chime in on Elizabeth Taylor, Montgomery Clift, Clark Gable, Frank Sinatra, Arthur Miller, and dozens of other famous names and faces. Though an awful lot of fun, the film is disjointed, lacking a central focus, and the onscreen titles, end credits, and promotional postcards are chock-full of typos — perhaps emulating a Chinese takeout menu, hence the film’s title? Chop Suey is screening November 20 at 7:00 as part of Film Forum’s “Bruce Weber” series and will be preceded by Weber’s twelve-minute 2008 short, The Boy Artist; the series continues through November 21 with a 35mm print of Let’s Get Lost, 1987’s Broken Noses, about former Olympian boxer Andy Minsker, 2004’s A Letter to True, a tribute to Weber’s dog, and a compilation of shorts, videos, commercials, and works in progress.

Fashion photographer Bruce Weber, who directed the seminal Chet Baker doc Let’s Get Lost a quarter century ago, made this fun hodgepodge of still photos, old color and black-and-white footage, and new interviews and voice-over narration back in 2001. You might not know much about Frances Faye, but after seeing her perform in vintage Ed Sullivan clips and listening to her manager/longtime partner discuss their life together, you’ll be searching YouTube to check out a lot more. The film also examines how Weber selects and treats his male models, who are often shot in homoerotic poses for major designers (and later go on to get married and have children). As a special treat, Jan-Michael Vincent’s extensive full-frontal nude scene in Daniel Petrie and Sidney Sheldon’s 1974 Buster and Billie is on display here, as are vintage clips of Sammy Davis Jr., adventurer Sir Wilfred Thesiger, former Vogue editor Diana Vreeland, and Robert Mitchum singing in a recording studio with Dr. John. The film is about model Peter Johnson and Weber as much as it is about the cult of celebrity; Weber gets to chime in on Elizabeth Taylor, Montgomery Clift, Clark Gable, Frank Sinatra, Arthur Miller, and dozens of other famous names and faces. Though an awful lot of fun, the film is disjointed, lacking a central focus, and the onscreen titles, end credits, and promotional postcards are chock-full of typos — perhaps emulating a Chinese takeout menu, hence the film’s title? Chop Suey is screening November 20 at 7:00 as part of Film Forum’s “Bruce Weber” series and will be preceded by Weber’s twelve-minute 2008 short, The Boy Artist; the series continues through November 21 with a 35mm print of Let’s Get Lost, 1987’s Broken Noses, about former Olympian boxer Andy Minsker, 2004’s A Letter to True, a tribute to Weber’s dog, and a compilation of shorts, videos, commercials, and works in progress.