The long friendship Henry Fonda and Jimmy Stewart is the focus of terrific three-week series at Film Forum

Film Forum

209 West Houston St.

October 27 – November 16

212-727-8110

filmforum.org

If only America were more like the long relationship between Nebraska-born Oscar winner Henry Jaynes Fonda and Pennsylvania-born Oscar winner James Maitland Stewart. Fonda, who served in the Navy during WWII and passed away in 1982 at the age of seventy-seven, was a liberal Democrat who was married five times; Stewart, who served in the Army during WWII and passed away in 1997 at the age of eighty-nine, was married to the same woman for forty-four years. Not only did Hank and Jim disagree on politics, which they early on decided never to talk about in each other’s company, but they also went head-to-head for the Best Actor Oscar in 1941, when Stewart (The Philadelphia Story) beat Fonda (The Grapes of Wrath). Still, they remained best buddies, which is documented in Scott Eyman’s new book, Hank and Jim: the Fifty-Year Friendship of Henry Fonda and James Stewart (October 24, Simon & Schuster, $29), a tome that serves as the inspiration behind the fab Film Forum series “Hank and Jim,” running October 27 through November 16, consisting of more than three dozen movies made by the two actors, who both experienced success on Broadway as well as in Hollywood. (The onetime roommates met while trying to establish their careers in New York City.) Eyman will be at Film Forum to introduce several screenings and sign copies of his book.

The series begins October 27 with an Alfred Hitchcock double feature, The Wrong Man, starring Fonda as a jazz musician accused of murder, and Rope, in which Stewart plays a professor invited to a dinner party with an unexpected guest. That is followed October 28 with Sidney Lumet’s 12 Angry Men and Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, in which Fonda and Stewart both portray men with consciences who care about fairness and the truth. Other double features with films made by each man include The Ox-Bow Incident and Broken Arrow, Call Northside 777 and The Boston Strangler, The Moon’s Our Home and Next Time We Love, and Destry Rides Again and Daisy Kenyon, in addition to double features with just one of them and individual screenings of some of their greatest solo films. Fonda and Stewart made only three movies in which they appeared together, On Our Merry Way, Vincent McEveety’s Firecreek, and Gene Kelly’s The Cheyenne Social Club, but, oddly, none of them is part of this festival, nor is How the West Was Won, which stars both of them but they are never in the same scene.

Sidney Lumet’s 12 Angry Men explores the consciences and more of a dozen jurors deciding a murder case

12 ANGRY MEN (Sidney Lumet, 1957)

Film Forum

Saturday, October 28, 3:00, 7:30

www.filmforum.org

The fate of an eighteen-year-old boy charged with the murder of his father is at stake in Sidney Lumet’s first film, the gripping, genre-defining 12 Angry Men. After a series of establishing shots, a judge sends a dozen New Yorkers into the jurors room, where they need to come to a unanimous verdict that could lead to the execution of the teen. Over the course of about ninety minutes, an all-star cast examines and reexamines the case — and their own personal biases — as the heat increases, both literally and figuratively. At first, the nameless dozen men make small talk, trying to be friendly, but it’s not long before some of them are at others’ throats, primarily the gruff Lee J. Cobb, who has it in for the calm and thoughtful Henry Fonda, who is ready to stand alone if necessary for what he believes in. The other uniformly excellent actors playing a very specific cross-section of white, male America are John Fiedler, Martin Balsam, Robert Webber, E. G. Marshall, Jack Klugman, Edward Binns, Jack Warden, Ed Begley, Joseph Sweeney, and George Voskovec. “I tell you, we were lucky to get a murder case,” Webber tells Fonda, but he won’t feel the same as the tension reaches near-violent proportions. 12 Angry Men is a searing examination of the criminal justice system as well as basic human instincts, behavior, and common decency. The Philadelphia-born Lumet, whose parents were both in the Yiddish theater, is able to tell the story in cinematic ways despite its taking place mostly in one small, sweaty room, letting the intense acting drive the narrative; the director, who was nominated for an Oscar for the film, would go on to make such other classic New York City dramas as The Pawnbroker, The Anderson Tapes, Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, and Prince of the City. Nominated for a Best Picture Oscar and winner of the Golden Bear at Berlin, 12 Angry Men, based on an original teleplay by Reginald Rose, is screening October 28 as part of a double feature with Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington in the Film Forum series “Hank and Jim”; the 7:30 show will be introduced by Scott Eyman, author of Hank and Jim: the Fifty-Year Friendship of Henry Fonda and James Stewart, and followed by a book signing.

The fate of an eighteen-year-old boy charged with the murder of his father is at stake in Sidney Lumet’s first film, the gripping, genre-defining 12 Angry Men. After a series of establishing shots, a judge sends a dozen New Yorkers into the jurors room, where they need to come to a unanimous verdict that could lead to the execution of the teen. Over the course of about ninety minutes, an all-star cast examines and reexamines the case — and their own personal biases — as the heat increases, both literally and figuratively. At first, the nameless dozen men make small talk, trying to be friendly, but it’s not long before some of them are at others’ throats, primarily the gruff Lee J. Cobb, who has it in for the calm and thoughtful Henry Fonda, who is ready to stand alone if necessary for what he believes in. The other uniformly excellent actors playing a very specific cross-section of white, male America are John Fiedler, Martin Balsam, Robert Webber, E. G. Marshall, Jack Klugman, Edward Binns, Jack Warden, Ed Begley, Joseph Sweeney, and George Voskovec. “I tell you, we were lucky to get a murder case,” Webber tells Fonda, but he won’t feel the same as the tension reaches near-violent proportions. 12 Angry Men is a searing examination of the criminal justice system as well as basic human instincts, behavior, and common decency. The Philadelphia-born Lumet, whose parents were both in the Yiddish theater, is able to tell the story in cinematic ways despite its taking place mostly in one small, sweaty room, letting the intense acting drive the narrative; the director, who was nominated for an Oscar for the film, would go on to make such other classic New York City dramas as The Pawnbroker, The Anderson Tapes, Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, and Prince of the City. Nominated for a Best Picture Oscar and winner of the Golden Bear at Berlin, 12 Angry Men, based on an original teleplay by Reginald Rose, is screening October 28 as part of a double feature with Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington in the Film Forum series “Hank and Jim”; the 7:30 show will be introduced by Scott Eyman, author of Hank and Jim: the Fifty-Year Friendship of Henry Fonda and James Stewart, and followed by a book signing.

MR. SMITH GOES TO WASHINGTON (Frank Capra, 1939)

Film Forum

Saturday, October 28, 12:30, 4:55

www.filmforum.org

We love Jimmy Stewart; we really do. Who doesn’t? But a few years ago we had the audacity to claim that Jim Parsons’s performance as Elwood P. Dowd in the 2012 Broadway revival of Harvey outshined that of Stewart in the treacly 1950 film, and now we’re here to tell you that another of his iconic films is nowhere near as great as you might remember, although it still has its place in the Hollywood canon. Nominated for eleven Academy Awards, Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington caused quite a scandal in America’s capital when it was released in 1939, depicting a corrupt democracy that just might be saved by a filibustering junior senator from a small state whose most relevant experience is being head of the Boy Rangers. (The Boy Scouts would not allow their name to be used in the film.) Stewart plays the aptly named Jefferson Smith, a dreamer who believes in truth, justice, and the American way. “I wouldn’t give you two cents for all your fancy rules,” Smith says of the Senate, “if, behind them, they didn’t have a little bit of plain, ordinary, everyday kindness and a little looking out for the other fella, too.” He’s shocked — shocked! — to discover that his mentor, the immensely respected Sen. Joseph Harrison Paine (played by Claude Rains, who was similarly shocked that there was gambling at Rick’s in Casablanca), is not nearly as squeaky clean as he thought, involved in high-level corruption, manipulation, and pay-offs that nearly drains Smith of his dreams. Having recently celebrated its seventy-fifth anniversary, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is still, unfortunately, rather relevant, as things haven’t changed all that much, but Capra’s dependence on over-the-top melodrama has worn thin. It’s a good film, but it’s no longer a great one. Just in time for election day, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is screening October 28 as part of a double feature with Sidney Lumet’s 12 Angry Men in the Film Forum series “Hank and Jim”; the 4:55 show will be introduced by Scott Eyman, author of Hank and Jim: the Fifty-Year Friendship of Henry Fonda and James Stewart, and followed by a book signing.

We love Jimmy Stewart; we really do. Who doesn’t? But a few years ago we had the audacity to claim that Jim Parsons’s performance as Elwood P. Dowd in the 2012 Broadway revival of Harvey outshined that of Stewart in the treacly 1950 film, and now we’re here to tell you that another of his iconic films is nowhere near as great as you might remember, although it still has its place in the Hollywood canon. Nominated for eleven Academy Awards, Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington caused quite a scandal in America’s capital when it was released in 1939, depicting a corrupt democracy that just might be saved by a filibustering junior senator from a small state whose most relevant experience is being head of the Boy Rangers. (The Boy Scouts would not allow their name to be used in the film.) Stewart plays the aptly named Jefferson Smith, a dreamer who believes in truth, justice, and the American way. “I wouldn’t give you two cents for all your fancy rules,” Smith says of the Senate, “if, behind them, they didn’t have a little bit of plain, ordinary, everyday kindness and a little looking out for the other fella, too.” He’s shocked — shocked! — to discover that his mentor, the immensely respected Sen. Joseph Harrison Paine (played by Claude Rains, who was similarly shocked that there was gambling at Rick’s in Casablanca), is not nearly as squeaky clean as he thought, involved in high-level corruption, manipulation, and pay-offs that nearly drains Smith of his dreams. Having recently celebrated its seventy-fifth anniversary, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is still, unfortunately, rather relevant, as things haven’t changed all that much, but Capra’s dependence on over-the-top melodrama has worn thin. It’s a good film, but it’s no longer a great one. Just in time for election day, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is screening October 28 as part of a double feature with Sidney Lumet’s 12 Angry Men in the Film Forum series “Hank and Jim”; the 4:55 show will be introduced by Scott Eyman, author of Hank and Jim: the Fifty-Year Friendship of Henry Fonda and James Stewart, and followed by a book signing.

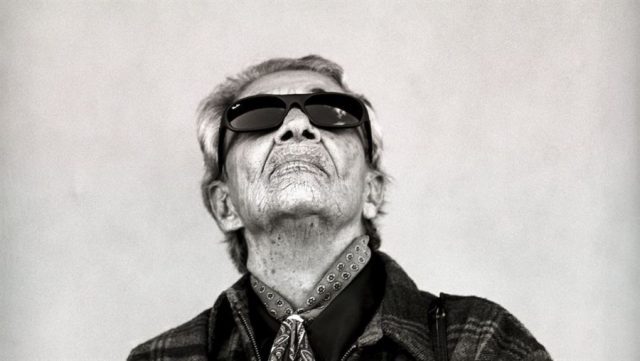

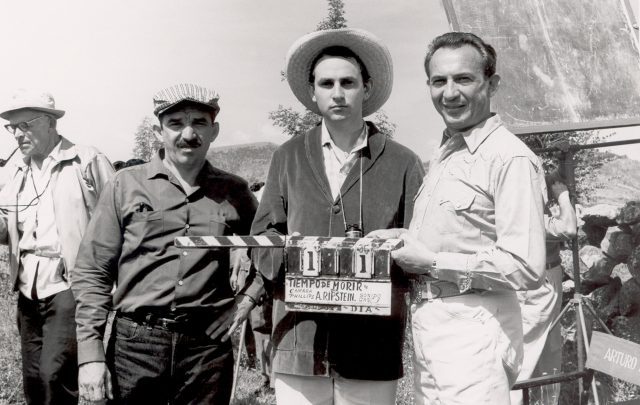

The extraordinary story of beloved Mexican ranchera singer Chavela Vargas is intricately documented in Catherine Gund and Daresha Kyi’s warm and intimate Chavela, opening at Film Forum today. Chavela’s life might seem an all-too-familiar archetype, the tale of a powerful female vocalist, a lesbian performer whose career was wrecked by the lethal combination of a heterosexual macho society, personal demons, and addiction, but Chavela avoids stereotypes and instead delivers a very human portrait. Born in Costa Rica in 1919, Chavela had an unhappy childhood and ran away to Mexico when she was fourteen to pursue a singing career and live a freer life, able to explore her sexual orientation as she grew older. “Her own parents saw her as a strange girl. They realized she was a boyish girl,” composer Marcela Rodríguez says. “Her movement, her hands, and her body language were manly.” Her longtime partner, human rights lawyer Alicia Pérez Duarte, adds, “Chavela created her persona in a very macho world.” Chavela dedicated her life to her music while keeping much of her personal life private — the film drops little more than tantalizing hints about her relationship with artist Frida Kahlo and an evening with Ava Gardner — and her commanding presence and powerful vocal style quickly made her a star in the 1940s and ’50s. “Hers wasn’t a sweet, crystal clear voice,” says cabaret owner Jesusa Rodríguez. “And she always sounded like she’d been torn apart, as if she’d been born with the wounds of life and death.” But at the height of her fame, those wounds started catching up to her as she began drinking heavily, resulting in a fifteen-year hiatus during which many people thought she was dead. The film centers around a never-before-seen 1991 interview Gund conducted with Chavela upon her return to singing, as she speaks more openly and honestly about her sexuality, her family, and her career. She’s a riveting figure, confident and determined, ready to face the world again. “We all have to live in the present. Don’t think about yesterday or tomorrow. Today,” she says.

The extraordinary story of beloved Mexican ranchera singer Chavela Vargas is intricately documented in Catherine Gund and Daresha Kyi’s warm and intimate Chavela, opening at Film Forum today. Chavela’s life might seem an all-too-familiar archetype, the tale of a powerful female vocalist, a lesbian performer whose career was wrecked by the lethal combination of a heterosexual macho society, personal demons, and addiction, but Chavela avoids stereotypes and instead delivers a very human portrait. Born in Costa Rica in 1919, Chavela had an unhappy childhood and ran away to Mexico when she was fourteen to pursue a singing career and live a freer life, able to explore her sexual orientation as she grew older. “Her own parents saw her as a strange girl. They realized she was a boyish girl,” composer Marcela Rodríguez says. “Her movement, her hands, and her body language were manly.” Her longtime partner, human rights lawyer Alicia Pérez Duarte, adds, “Chavela created her persona in a very macho world.” Chavela dedicated her life to her music while keeping much of her personal life private — the film drops little more than tantalizing hints about her relationship with artist Frida Kahlo and an evening with Ava Gardner — and her commanding presence and powerful vocal style quickly made her a star in the 1940s and ’50s. “Hers wasn’t a sweet, crystal clear voice,” says cabaret owner Jesusa Rodríguez. “And she always sounded like she’d been torn apart, as if she’d been born with the wounds of life and death.” But at the height of her fame, those wounds started catching up to her as she began drinking heavily, resulting in a fifteen-year hiatus during which many people thought she was dead. The film centers around a never-before-seen 1991 interview Gund conducted with Chavela upon her return to singing, as she speaks more openly and honestly about her sexuality, her family, and her career. She’s a riveting figure, confident and determined, ready to face the world again. “We all have to live in the present. Don’t think about yesterday or tomorrow. Today,” she says.

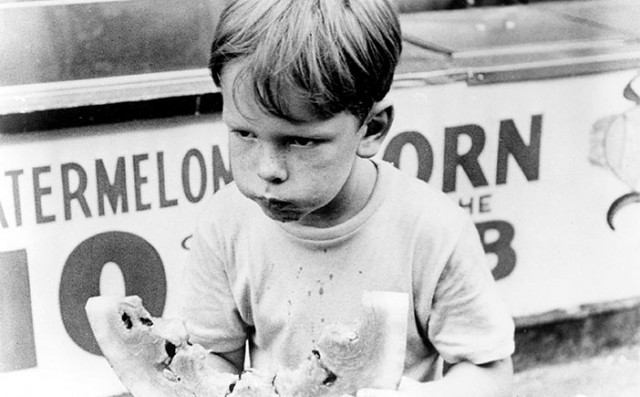

In between the two showings of Little Fugitive is another delightful treat, Ted Wilde’s Speedy, with live musical accompaniment by pianist Steve Sterner. Much like the end of the silent film era itself, the last horse-drawn trolley is doomed in Harold Lloyd’s final silent film. Big business is playing dirty trying to get rid of the trolley and classic old-timer Pop Dillon. Meanwhile, Harold “Speedy” Swift, a dreamer who wanders from menial job to menial job (he makes a great soda-jerk with a unique way of announcing the Yankees score), cares only about the joy and wonder life brings. But he’s in love with Pop’s granddaughter, Jane (Ann Christy), so he vows to save the day. Along the way, he gets to meet Babe Ruth. Wilde was nominated for an Oscar for Best Director, Comedy, for this thrilling nonstop ride through beautiful Coney Island and the pre-depression streets of New York City. Film Forum’s second annual Festival of Summer Double Features continues through September 5 with such other sweet pairings as Panique and Peeping Tom, Point Blank and The Killers, and The Big Lebowski and The Last Picture Show.

In between the two showings of Little Fugitive is another delightful treat, Ted Wilde’s Speedy, with live musical accompaniment by pianist Steve Sterner. Much like the end of the silent film era itself, the last horse-drawn trolley is doomed in Harold Lloyd’s final silent film. Big business is playing dirty trying to get rid of the trolley and classic old-timer Pop Dillon. Meanwhile, Harold “Speedy” Swift, a dreamer who wanders from menial job to menial job (he makes a great soda-jerk with a unique way of announcing the Yankees score), cares only about the joy and wonder life brings. But he’s in love with Pop’s granddaughter, Jane (Ann Christy), so he vows to save the day. Along the way, he gets to meet Babe Ruth. Wilde was nominated for an Oscar for Best Director, Comedy, for this thrilling nonstop ride through beautiful Coney Island and the pre-depression streets of New York City. Film Forum’s second annual Festival of Summer Double Features continues through September 5 with such other sweet pairings as Panique and Peeping Tom, Point Blank and The Killers, and The Big Lebowski and The Last Picture Show.

When rich kid Elgar Winthrop Julius Enders (Beau Bridges) finally decides to do something with his spoiled life of privilege, he takes a rather curious turn, buying a dilapidated tenement in a pregentrified Park Slope that resembles the South Bronx in Hal Ashby’s poignant directorial debut, The Landlord. At first, the less-than-worldly Elgar doesn’t quite know what he’s gotten himself into, believing it will be easy to kick out the current residents and then replace the decrepit building with luxury apartments. He pulls up to the place in his VW bug convertible, thinking he can just waltz in and do whatever he wants, but just as his car is vandalized, so is his previously charmed existence, as he gets to know wise house mother Marge (Pearl Bailey), the sexy Francine (Diana Sands), her activist husband, Copee (Louis Gossett Jr.), and Black Power professor Duboise (Melvin Stewart), none of whom is up-to-date with the rent. Meanwhile, Elgar starts dating Lanie (Marki Bey), a light-skinned half-black club dancer he assumed was white, infuriating his father, William (Walter Brooke), and mother, Joyce (a delightful, Oscar-nominated Lee Grant), who are in the process of setting up their daughter, Susan (Susan Anspach), with the white-bread Peter Coots (Robert Klein).

When rich kid Elgar Winthrop Julius Enders (Beau Bridges) finally decides to do something with his spoiled life of privilege, he takes a rather curious turn, buying a dilapidated tenement in a pregentrified Park Slope that resembles the South Bronx in Hal Ashby’s poignant directorial debut, The Landlord. At first, the less-than-worldly Elgar doesn’t quite know what he’s gotten himself into, believing it will be easy to kick out the current residents and then replace the decrepit building with luxury apartments. He pulls up to the place in his VW bug convertible, thinking he can just waltz in and do whatever he wants, but just as his car is vandalized, so is his previously charmed existence, as he gets to know wise house mother Marge (Pearl Bailey), the sexy Francine (Diana Sands), her activist husband, Copee (Louis Gossett Jr.), and Black Power professor Duboise (Melvin Stewart), none of whom is up-to-date with the rent. Meanwhile, Elgar starts dating Lanie (Marki Bey), a light-skinned half-black club dancer he assumed was white, infuriating his father, William (Walter Brooke), and mother, Joyce (a delightful, Oscar-nominated Lee Grant), who are in the process of setting up their daughter, Susan (Susan Anspach), with the white-bread Peter Coots (Robert Klein).