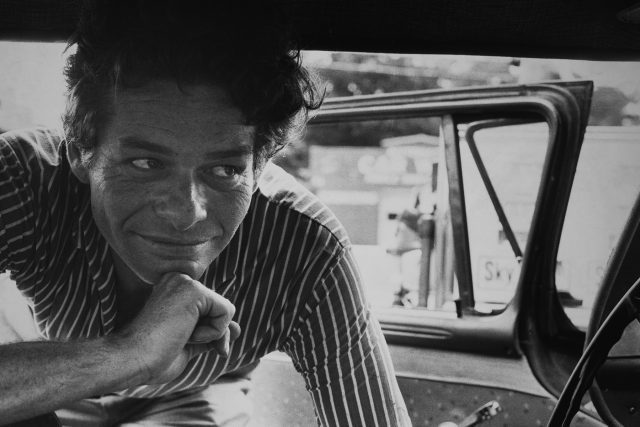

Robert (Robert Williams) attempts to charm Regina (Regina Williams) in Life and Nothing More

LIFE AND NOTHING MORE (Antonio Méndez Esparza, 2017)

Film Forum

209 West Houston St.

Through Tuesday, November 6

212-727-8110

filmforum.org

www.cafilm.org/lanm

Antonio Méndez Esparza’s follow-up to his debut, Aquí y Allá, is a sensitive, beautifully paced film that lives up to its title: Life and Nothing More. Inspired by Italian neorealism, Esparza employs a cinema vérité style to tell the story of Regina (Regina Williams), an African American single mother struggling to get by in Florida. Regina has a delightful three-year-old daughter (Ry’Nesia Chambers) and a quiet, distant fourteen-year-old son, Andrew (Andrew Bleechington), who is starting to get in trouble with the law, hanging around with bad kids and carrying around a knife. Regina works menial minimum-wage jobs to try to keep the family afloat while the father of her children is in prison. Robert (Robert Williams), a newcomer to the town, starts trying to charm her, wanting to take her out, but Regina is suspicious of his intentions, as is Andrew. But when Robert shows the least bit of threatening anger as he and Andrew clash, Regina has some difficult decisions to make, which grow more complicated when other facts come to light.

Antonio Méndez Esparza’s follow-up to his debut, Aquí y Allá, is a sensitive, beautifully paced film that lives up to its title: Life and Nothing More. Inspired by Italian neorealism, Esparza employs a cinema vérité style to tell the story of Regina (Regina Williams), an African American single mother struggling to get by in Florida. Regina has a delightful three-year-old daughter (Ry’Nesia Chambers) and a quiet, distant fourteen-year-old son, Andrew (Andrew Bleechington), who is starting to get in trouble with the law, hanging around with bad kids and carrying around a knife. Regina works menial minimum-wage jobs to try to keep the family afloat while the father of her children is in prison. Robert (Robert Williams), a newcomer to the town, starts trying to charm her, wanting to take her out, but Regina is suspicious of his intentions, as is Andrew. But when Robert shows the least bit of threatening anger as he and Andrew clash, Regina has some difficult decisions to make, which grow more complicated when other facts come to light.

Fourteen-year-old Andrew (Andrew Bleechington) has trouble connecting in Antonio Méndez Esparza’s Life and Nothing More

Cinematographer Barbu Balasoiu keeps his camera slow and steady as it lingers on scenes with very little or no dialogue, maintaining a tense mood that hovers over the film. As with Aquí y Allá, which was shot in Mexico, most of the actors are nonprofessionals in their first film, which heightens the reality. Regina Williams gives a strong, tenderhearted performance as the mother, a woman dedicated to making a better life for her children but continually runs into roadblocks beyond her control. Writer-director Esparza often focuses on her eyes as she watches events unfold, saying nothing but wanting to fight back more and more without risking the safety of her family. The film also smartly explores the incarceration gap between blacks and white without getting overtly political. Robert Williams (no relation) is engaging, with just the right hint of mystery and possible danger, while Bleechington reveals much with very few words, a boy who just can’t seem to say or do the right thing (when he speaks at all). Winner of awards at film festival around the world in addition to the Independent Spirit John Cassavetes Award, Life and Nothing More is an honest, nuanced look at race and class in twenty-first-century America, an intelligent and heartbreaking depiction of what life is like for so many people today.

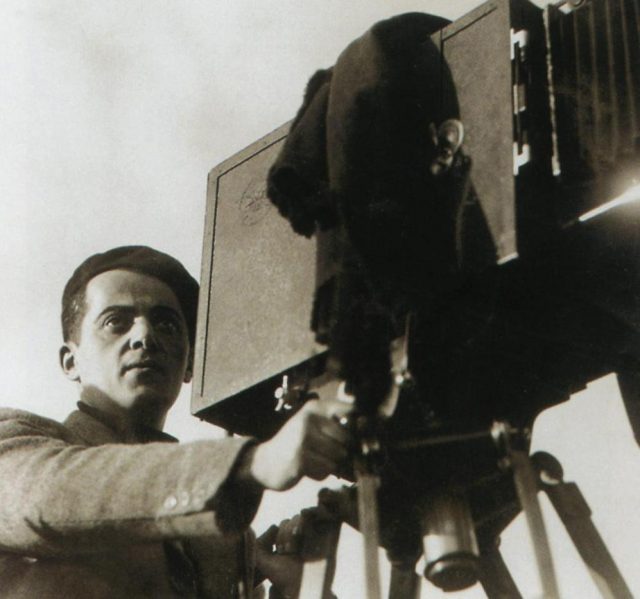

French auteur Jean Vigo made only three shorts and one feature before his death from tuberculosis and leukemia in 1934 at the age of twenty-nine, but his wide-ranging legacy continues. Film Forum pays tribute to his lasting influence on cinema with “The Complete Jean Vigo,” new 4K restorations of all of his works in addition to a new bonus. In Vigo’s fourth and final film, L’Atalante, his only feature, Swiss actor Michel Simon is spectacularly hilarious as an aging, somewhat decrepit first mate with a peculiar lust for life and cats. After barge captain Jean (Jean Dasté) and Juliette (Dita Parlo) get married in her small, tight-knit country town, they head for the big city of Paris on the long boat, L’Atalante, that he captains as his job. First mate Père Jules (Simon) and his young cabin boy (Louis Lefebvre) come along for the would-be honeymoon, attempting to make sure it’s a smooth ride, which of course it’s not. Juliette wants to enjoy the Parisian nightlife, Jean is a jealous, overprotective stick-in-the-mud, and Père Jules — well, Père Jules is downright unpredictable, pretty much all id, living life footloose and fancy free even if he doesn’t have much money or many true friends. When a love-struck bicycle-riding peddler (Gilles Margaritis) tries to woo Juliette, Jean grows angry, and an emotional and psychological battle ensues. But through it all, Père Jules just keeps on keepin’ on, never getting too concerned, confident that everything will work out in the end, because that’s what happens in life.

French auteur Jean Vigo made only three shorts and one feature before his death from tuberculosis and leukemia in 1934 at the age of twenty-nine, but his wide-ranging legacy continues. Film Forum pays tribute to his lasting influence on cinema with “The Complete Jean Vigo,” new 4K restorations of all of his works in addition to a new bonus. In Vigo’s fourth and final film, L’Atalante, his only feature, Swiss actor Michel Simon is spectacularly hilarious as an aging, somewhat decrepit first mate with a peculiar lust for life and cats. After barge captain Jean (Jean Dasté) and Juliette (Dita Parlo) get married in her small, tight-knit country town, they head for the big city of Paris on the long boat, L’Atalante, that he captains as his job. First mate Père Jules (Simon) and his young cabin boy (Louis Lefebvre) come along for the would-be honeymoon, attempting to make sure it’s a smooth ride, which of course it’s not. Juliette wants to enjoy the Parisian nightlife, Jean is a jealous, overprotective stick-in-the-mud, and Père Jules — well, Père Jules is downright unpredictable, pretty much all id, living life footloose and fancy free even if he doesn’t have much money or many true friends. When a love-struck bicycle-riding peddler (Gilles Margaritis) tries to woo Juliette, Jean grows angry, and an emotional and psychological battle ensues. But through it all, Père Jules just keeps on keepin’ on, never getting too concerned, confident that everything will work out in the end, because that’s what happens in life.

![New York, 1968 [laughing woman with ice cream] Photographs by Garry Winogrand, Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona. © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.](https://twi-ny.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/garry-winogrand-2-e1537325349352.jpg)