Whitney White reimagines Shakespeare tragedy in rousing Macbeth in Stride at BAM (photo by Marc J. Franklin)

MACBETH IN STRIDE

Brooklyn Academy of Music

Harvey Theater at the BAM Strong

651 Fulton St.

April 15-27, $29-$85

www.bam.org/macbeth

Whitney White’s Macbeth in Stride is an exhilarating hijacking of Shakespeare’s Scottish play, transforming it into an empowering and unrelenting Black feminist rock opera that serves as a takedown of the traditional roles assigned to women not only in the Bard’s canon but in theater and the world itself.

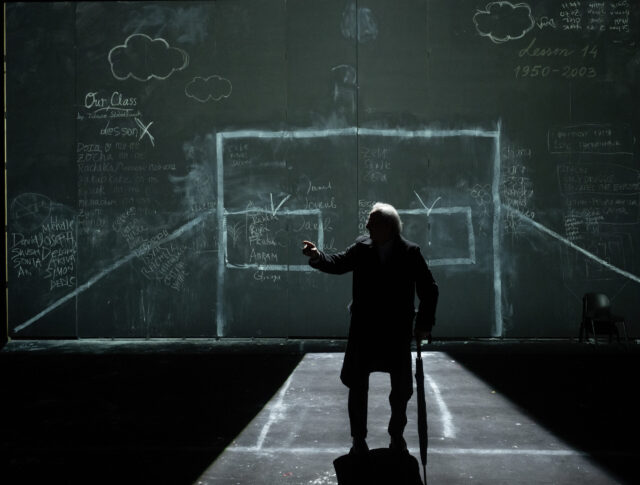

“Irreverence is everything,” White notes at the beginning of her multilayered, irreverent script. Best known as the award-winning director of such plays as Jaja’s African Hair Braiding, On Sugarland, soft, and Liberation, White is both the author and star of this dazzling production at BAM’s Harvey Theater. The ninety-minute show is fervently directed with plenty of winks and nods by Taibi Magar (Help, Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992) and Tyler Dobrowsky, who previously collaborated with White (and Peter Mark Kendall) on the virtual pandemic concert play Capsule.

In Macbeth in Stride, White portrays an unnamed woman who is the dazzling lead singer of a hot band and an actress playing Lady Macbeth. Holli’ Conway, Phoenix Best, and Ciara Alyse Harris are a trio of backup vocalists, the three witches, and a kind of Greek chorus; everyone interacts with the audience, starting with the sensational opening number, “If Knowledge Is Power.”

“So what’s the story?” the woman, dressed in a tight-fitting black sparkling pantsuit, asks in her speech following the song. “For me . . . tonight there is one story — one play in particular that kicked it all off / The funky little chain reaction that led someone like me / To be standing before you now / That led someone like me from where I’m from / To school and stage and work and rehearsals / And kept me up many nights / But for now let’s get back to all of you / Let’s stick with you. / What’s the story you told yourselves to get here?”

Macbeth is introduced in the next song, “Reach for It,” in which several characters sing, “So if foul is fair then fair is foul / Ambition’s not a sin at all!,” after which the woman proclaims she wants ambition and love, no matter that the witches tell her women cannot have both. She also is intent on flipping the switch on Shakespeare, since all of his “great women never seem to make it out of these plays alive!”

The man playing Macbeth (Charlie Thurston) arrives, a white accordionist clad in black leather. Learning that he is destined to be king, she realizes that she in turn would become queen and wants the power that comes with that, to be more than the secondary character Lady M is through much of the original play. She asks the audience, “Women, queer folk, and othered people out there? / What are you willing to do to get what you need? / To get what you want?” She admits that violence might be the answer.

When Macbeth tells Lady M that King Duncan will be staying the night at their castle, she advises her husband, “I’m pretty sure we’re gonna have to kill him.” He does the deed, she frames the guards, and they become king and queen. As he deals with a heavy dose of fear, suspicion, and guilt, she is determined to be more than an appendage who just gets to host dinner parties; instead, she is going to “reclaim everything.”

Whitney White and Charlie Thurston star as the doomed couple in meta-heavy Macbeth in Stride (photo by Marc J. Franklin)

Macbeth in Stride is a rousing reimagining of Shakespeare’s 1606 tragedy, a clever, passionate, and downright fun show that celebrates the freeing of women from the shackles of literature as well as the chains of real life. White’s Lady M is a symbol of changing the narrative and taking control of the story, in this case in the guise of a spectacular concert. Songs such as “Dark World,” “Doll House,” and “I for You” help place the tale in contemporary times. “You gon’ rework a four hundred year old play just for your ego?” the first witch asks White, who replies, “Yup. / Sure did! Sure did!”

Dan Soule’s set features several platforms and a diagonal walkway cutting through the middle. Jeanette Oi-Suk Yew lights the show like a concert, including vertical strips of colored lights, while Nick Kourtides’s sound balances the loud music with the less raucous dialogue. Qween Jean’s costumes are fashionably glitzy, as is Raja Feather Kelly’s choreography.

The crack band consists of music director Nygel D. Robinson on keyboards, Kenny Rosario-Pugh on guitar, Bobby Etienne on bass, and Barbara “Muzikaldunk” Duncan on drums. Conway (Six, Tina), Best (Dear Evan Hansen, Teeth), and Harris (Dear Evan Hansen, White Girl in Danger) excel as the chorus, who are worthy of their own show. Thurston (Liberation, Here There Are Blueberries) succeeds in a nearly impossible task, surrounded by strong, tenacious women.

White, who also sits at the piano for a few tunes, is right at home center stage. She might not always have the range the songs require — “Reach for It” is a bit of a reach for her — but she embodies her character with an intense grandeur that is as intoxicating as it is fierce.

Shakespeare purists will notice occasional iambic pentameter in the streamlined text, and most of the famous quotes are in there, in one form or another. However, since this is Lady M’s story, aside from Duncan, whose murder is described in some detail, there is no mention of Macduff and his family, no King Edward, no Donalbain and Malcolm, no visible ghosts, no Earl of Northumberland, no noblemen and doctors, no Birnam Wood, and only one mention of Banquo and his son.

As the end approaches, the woman wonders, “Why do they write us this way? / Why do they imagine us this way?”

White has picked up a sharp quill and stands boldly under the spotlight to write it her way. The script notes that Macbeth in Stride is the first of a four-part series; I can’t wait to see what she has in store for us next.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]