April Matthis is fabulous as the only person of color in Claudia Rankine’s Help (photo by Kate Glicksberg for the Shed)

HELP

The Griffin Theater at the Shed

The Bloomberg Building at Hudson Yards

545 West 30th St. at Eleventh Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through April 10, $29-$77

646-455-3494

theshed.org

Poet, playwright, and professor Claudia Rankine wanted to know what white people were thinking, so she asked them. The results can be seen in the blistering new show Help, which opened last night at the Shed’s Griffin Theater.

Several recent plays by Black playwrights, including David Harris’s Tambo & Bones, Jordan E. Cooper’s Ain’t No Mo’, and Jackie Sibblies Drury’s Fairview, have used fictional narratives to address systemic racism, breaking the fourth wall and directly confronting the predominantly white audience.

But Rankine goes right to the facts in Help, which consists of verbatim dialogue from interviews with white men and white women conducted separately by Rankine, who is Black, filmmaker Whitney Dow, who is white, and civil rights activist and theologian Ruby Nell Sales, who is Black; responses to Rankine’s 2019 New York Times article “I Wanted to Know What White Men Thought About Their Privilege. So I Asked”; and quotes from such politicians, writers, and other public figures as James Baldwin, Elon Musk, Marjorie Taylor Greene, Audre Lord, Donald Trump, Eddie Murphy, Bill Gates, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Dr. Richard Sackler, Mitch McConnell, Toshi Reagon, and Fred Moten.

Obie winner April Matthis hosts the evening as the Narrator, portraying a version of Rankine, speaking straight to the audience. “I am here — not as I — but as we — a representative of my category,” she says at the start. “The approximately eight percent of the U.S. population known as Black women.” After listing a few real names and epithets of Black women, she declares, “Ultimately, whatever name you use, all of them, begin with the letter N.”

She walks back and forth across the front of the long, horizontal stage, either holding a microphone or stopping at the stand near the middle, like a comedian performing a semiautobiographical one-person show. Although the ninety-minute play has plenty of laughs, it is also deadly serious when it comes to racism, white supremacy, reverse racism, and white privilege. And she’s not about to let the mostly white theatergoers off the hook because they have bought a ticket to see such a progressive show and clap at all the politically correct moments.

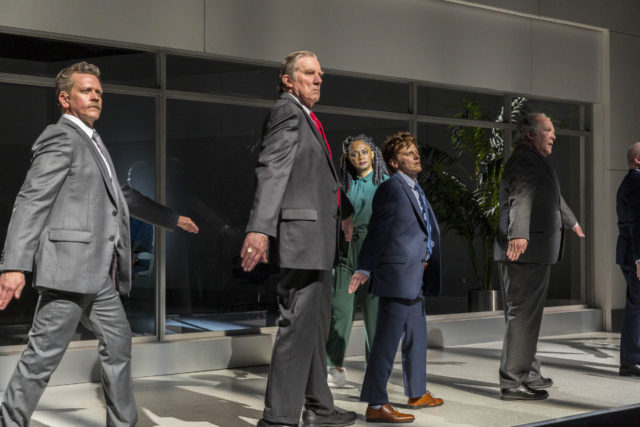

White men and women display their privilege through dance in Help (photo by Kate Glicksberg for the Shed)

Behind the Narrator is a glassed-in airport waiting room populated by nine white men and two white women in business attire, a stark contrast to the Narrator’s green jumpsuit. They often interact with her, either joining her at the front or welcoming her into their space. Actually, “welcoming” might not be the best word, because they usually don’t like what she has to say, even though she attempts to be neutral, not responding the way she wants to as they refuse to acknowledge the advantages their whiteness automatically brings them and turning it back on her.

In an early vignette, people are lining up to board a plane, in number order according to their ticket. The Narrator wants to make sure she is in the right spot but is not thrilled when one man (Jeremy Webb) says to another (Tom O’Keefe), “You never know who they’re letting into first class these days.” In a sidebar, her therapist (Tina Benko) tells her, “You didn’t matter to him. That’s why he could step in front of you in the first place. His embarrassment, if it was embarrassment, had everything to do with how he was seen by the person who did matter: his male companion. He made a mistake in front of his companion. You are allowing yourself to have too much presence in his imagination.”

The Narrator responds, “I want a new narrative, one that doesn’t demand, or require, or want . . . one that doesn’t accept my invisibility. I need a narrative that includes your whiteness as part of the diagnosis. . . . The limits of his world are the limits of your world too.” She’s not speaking to just the therapist but to everyone in the theater.

A few moments later, the Narrator assumes the man (Nick Wyman) in front of her voted for Trump, and he snidely replies, “You can stand in this line with me, but you’ll never be in line with me. That’s why I’ll vote for him again. And again.” And another (Rory Scholl) doesn’t hesitate to admit to her, “If the cost of my way of life is your life — that’s not my concern.”

It’s a war of words, interpretations, meanings, and intent that makes for an uneasy flight as she leads us through barrages of racist statements made by familiar names (identified specifically in the play’s online resources page) as well as a few brief chats in which the other person wants to be an ally but doesn’t know how to deal with their inherent privilege. She won’t even give her husband (O’Keefe), who is white, a break. “I’m not demonizing, I’m historicizing,” she tells us. “To stay alive, forget thriving, I need to negotiate whiteness.”

The white cast, which also includes Jess Barbagallo, David Beach, Charlotte Bydwell, Zach McNally, Joseph Medeiros, John Selya, and Charlette Speigner, occasionally breaks into group social dances, choreographed by Shamel Pitts, that sometimes involve the rolling waiting room chairs as the men and women put their whiteness on further display. The original music is by JJJJJerome Ellis and James Harrison Monaco, with sound by Lee Kinney, lighting by John Torres and costumes by Dede Ayite; Nicole Brewer is the antiracist coordinator.

The Narrator (April Matthis) navigates through a white world in Claudia Rankine play (photo by Kate Glicksberg for the Shed)

Over the last two years, Rankine (Just Us: An American Conversation, Citizen: An American Lyric) and Obie-winning director Taibi Magar (Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992, Is God Is) reshaped and updated the play, which had to shut down during previews in March 2020 because of the pandemic, working in the January 6 insurrection, the murder of George Floyd, the Covid-19 crisis, and other recent events, although there is, unfortunately, a timeless quality to everything, as racism doesn’t look like it’s going away soon. They’re not teaching or preaching, but they steadily navigate so the audience doesn’t feel backed into a corner.

At the center of it all is Matthis (Toni Stone, Fairview), who is brilliant as the Narrator, guiding the interactions while making sure the audience remains uncomfortable even when laughing, since Rankine pulls no punches. “Imagine if my fellow travelers were to wrestle with their own privilege, instead of with my presence. For once,” she says. Once again, she’s not just referring to the characters in the play; we’re all in the waiting room together.

Tony winner Mimi Lien’s fab set matches the Narrator’s description of it as a “liminal space, a space neither here nor there, a space we move through on our way to other places, a space full of imaginative possibilities.” Clearly, it’s white people who are doing most of the moving as minorities face more of a stasis. “There’s no outrunning the kingdom, the power, and the glory,” the Narrator reminds us. Meanwhile, another white man (Beach) insists, “The dominant culture is colorless,” later adding that classic phrase, “I don’t see color.”

The program features several excellent essays, by Rankine, Dow, Simone White, and Sales, who, in “Can We Just Get Down to the Conversation About Whiteness?,” writes, “We must ask, is it a privilege to inherit a death driven system that predicates itself on the decimation of the potential and possibility of white men to reach the fullness of their humanities? Contrary to calling out the worst in them as the system does, we must see the good in them that they do not see in themselves. Our work must enable them to find new meaning in their lives and provide relief from their brokenness and fragmentation.” Help is no mere attack on whiteness but a declaration that things can and must change, with help from everyone.

The Narrator sums it up best when she says, “There is, after all, no racism without racists.” At its heart, the show is about the fear that pervades white people who are desperately trying to hold on to the past, and their power, as the world changes right before their eyes. They’re afraid they and their kids won’t get into the right schools, won’t get the good jobs, won’t have the same opportunities they’ve had for more than two hundred years since the birth of the nation.

At the end of her writer’s note, Rankine points out, “As Ruby Sales has said, ‘There’s nothing wrong with being European American; that’s not the problem. It’s how you actualize that history and how you actualize that reality.’” And that’s what Help is about.