A muscleman (Ryan-James Hatanaka) shows off his wares to Grandma (Phyllis Somerville) in Edward Albee’s THE SANDBOX (photo by Monique Carboni)

The Pershing Square Signature Center

The Alice Griffin Jewel Box Theatre

480 West 42nd St. between Tenth & Eleventh Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through June 19, $25-$65

212-244-7529

www.signaturetheatre.org

As part of its twenty-fifth anniversary celebration, the Signature Theatre has put together an evening of compellingly strange one-acts that were previously presented by the company as part of their authors’ Playwright-in-Residence seasons all of which involve unique looks at death. In Edward Albee’s 1959 The Sandbox, first mounted at the Signature in 1994 directed by Albee himself, a WASPy couple who refer to each other as Mommy (Alison Fraser) and Daddy (Frank Wood) relax on lounge chairs after having an impressively toned muscleman in a bathing suit (Ryan-James Hatanaka) deposit Grandma (Phyllis Somerville) in a child’s sandbox on a nearly blindingly yellow set (by Mimi Lien). While Melody Giron plays the cello, the man continues his calisthenics, slowly flapping his arms while standing firmly on the ground, Mommy and Daddy find that they have little to talk about it, and Grandma marvels at the young man’s body while expressing her dismay at her situation. “Honestly! What a way to treat an old woman! Drag her out of the house . . . stick her in a car . . . bring her out here from the city . . . dump her in a pile of sand . . . and leave her here to set. I’m eighty-six years old!” she tells the audience. All of the characters are aware that they are in a play, making comments about the music, the lighting, and the script, but only Grandma, who embodies the entire life cycle, from baby to sexual being to mother to old woman on her last legs, speaks like a real person; the others are more like clichéd stock characters reciting their lines with the sparest of genuine emotion. Director Lila Neugebauer keeps it all bright and cheery as the end nears, in more ways than one.

Roe (Sahr Ngaujah) teaches Pea (Mikéah Ernest Jennings) about life in María Irene Fornés’s DROWNING (photo by Monique Carboni)

María Irene Fornés’s 1986 Drowning, initially presented at the Signature in 1999, when John Simon declared in New York magazine that it was “the worst play I have seen all year,” was originally part of Orchards, in which seven contemporary playwrights (among them Wendy Wasserstein, David Mamet, and John Guare) wrote a one-act play inspired by a short story by Anton Chekhov. Cuban-American playwright Fornés chose “Drowning,” although her avant-garde approach was more than a little unusual. In a cafeteria, Pea (Mikéah Ernest Jennings) and Roe (Sahr Ngaujah), a pair of giant potato-like creatures (Kaye Voyce’s elaborate costumes are a certifiable riot), talk ever-so-slowly, almost like a Butoh dance, as the latter teaches the former about newspapers, snow, and flesh. Fornés evokes Beckett as Roe and Pea wait for Stephen (Wood), who actually does show up, and the immature, childlike Pea learns about love and pain. “He is very kind and he could not do harm to anyone,” Stephen says about Roe, who responds, “Yes. And I don’t want any harm to come to him either because he’s good.” Drowning is a bizarre yet captivating journey into what makes us human.

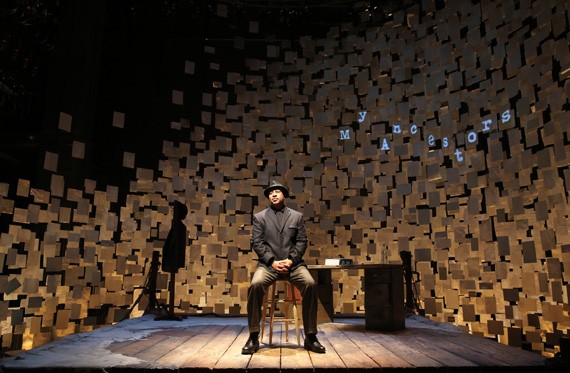

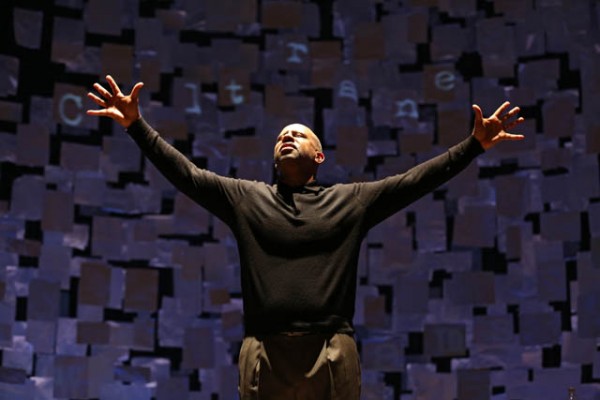

Adrienne Kennedy’s FUNNYHOUSE OF A NEGRO takes place inside of the mind of young woman facing a harsh reality (photo by Monique Carboni)

The Legacy Program evening concludes with Adrienne Kennedy’s Obie-winning 1964 Funnyhouse of a Negro, which was staged at the Signature in 1995. A complex exploration of slavery, racism, colonialism, and heritage, the entire story takes place inside the mind of Negro-Sarah (Crystal Dickinson) as she encounters Queen Victoria Regina (April Matthis), the Duchess of Hapsburg (January LaVoy), Patrice Lumumba (Ngaujah), and Jesus (Jennings) in addition to her roommate, Raymond (Nicholas Bruder), her landlady (Fraser), and the Mother (Pia Glenn). “My mother was the light. She was the lightest one. She looked like a white woman,” Victoria says. “Black man, black man, I never should have let a black man put his hands on me. The wild black beast raped me and now my skull is shining,” the Mother states. Negro (Sarah) adds, “As for myself I long to become even a more pallid Negro than I am now; pallid like Negroes on the covers of American Negro magazines; soulless, educated, and irreligious. I want to possess no moral value, particularly value as to my being. I want not to be. I ask nothing except anonymity.” And Sarah explains, “The rooms are my rooms; a Hapsburg chamber, a chamber in a Victorian castle, the hotel where I killed my father, the jungle. These are the places myselves exist in. I know no places. That is, I cannot believe in places. To believe in places is to know hope and to know the emotion of hope is to know beauty. It links us across a horizon and connects us to the world. I find there are no places only my funnyhouse.” Each scene takes place in a different, exquisitely designed set by Lien amid darkness and Voyce’s extravagant costumes. Like The Sandbox and Drowning, Funnyhouse of a Negro is a highly stylized, absurdist drama about death, and the death of the American dream, only this time with more overt targets and explicit, at times shocking action. It’s unfortunately still relevant a half century after its debut during the civil rights movement. It’s also a fitting finale to this Signature hat trick that looks back while also peering into the future.