A documentary filmmaker (Page Leong) looks back at her life in Anna Ouyang Moench’s My Documentary (photo by Joan Marcus)

OUT OF TIME

Martinson Theater, the Public Theater

425 Lafayette St. at Astor Pl.

Tuesday through Sunday through March 13, $60

212-539-8500

publictheater.org

www.naatco.org

In Sam Chanse’s Disturbance Specialist, the last of five monologues comprising Out of Time, author Leonie Z. (Natsuko Ohama) says, “You know nothing of what it is to live when you haven’t yet understood that you will die. And none of you really understands that. You get the concept maybe but you don’t actually believe it.”

Out of Time, which opened last night at the Public’s Martinson Theater, is an extraordinary concept: Five Asian American playwrights have written monologues for five Asian American actors over the age of sixty, directed by Les Waters, who is also over sixty. The five stories don’t always focus on aging, although getting older, with fewer years ahead than behind, is an inherent theme throughout the works, as is the call for respect for the elderly from family, friends, colleagues, and strangers. Isolation, loss, and loneliness abound, along with deep pockets of hope and defiance.

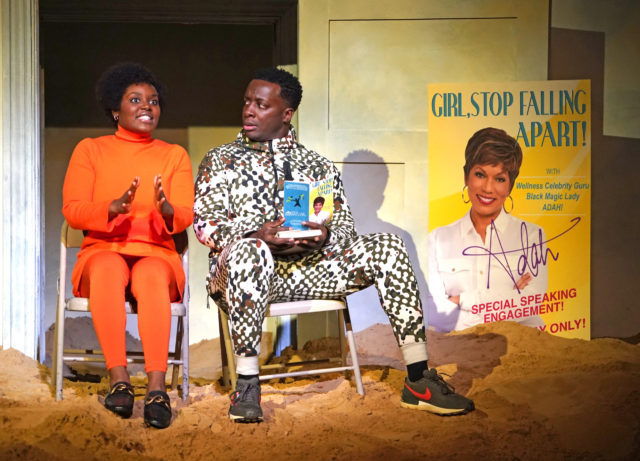

Speaking about her longtime producer, the unnamed documentary filmmaker (Page Leong) in Anna Ouyang Moench’s My Documentary explains, “Neil, who hugged me hello and then listened to my carefully crafted pitch about my just-dead husband and passed and hugged me goodbye as though he hadn’t just told a widow in no uncertain terms to go fuck herself because she’s old and no one cares when old people grieve other old people.”

Ena (Mia Katigbak) knows getting older is no mere game in Mia Chung’s Ball in the Air (photo by Joan Marcus)

In Mia Chung’s Ball in the Air, Ena (Mia Katigbak) walks onto the stage playing with a kids’ paddle ball, bouncing a little red ball against a wooden paddle, the two held together tenuously by a thin rubber band. She displays a childlike desire to succeed at the game shortly before describing a horrible accident she was involved in. She worries about feeling confused as different stories merge together in her mind. “Time is no guarantee,” she says. “These moments — when someone sees red when you see blue — well, it can be a stunner. It can seem as if something has vanished. In an instant.”

Glenn Kubota is the only male in the cast, portraying Taki in Naomi Iizuka’s Japanese Folk Song. The Scotch- and cigar-loving, jazz-hating Taki details how he nearly died in every decade from his teens to his seventies — “I must be pretty tough,” he acknowledges. “And lucky. I must be lucky.” — before telling a version of the Japanese ghost story “Yuki-onna,” which was famously retold in Masaki Kobayashi’s classic film Kwaidan. Taki is straightforward and practical even as he ventures into the realm of the fantastic.

Carla (Rita Wolf) is a voice from the past discussing the history of cancer among the women in her family in Jaclyn Backhaus’s Black Market Caviar. The piece is structured as a video the character made on December 31, 2019, offering advice to a descendant watching decades later. “Time is moving more quickly than I’d like,” she says. Carla is sitting behind a translucent curtain; we watch her on a video monitor at the corner of the stage. Ena, Taki, and the documentarian all sit in chairs front and center, evoking Waters’s direction of Lucas Hnath’s Dana H., in which Deirdre Connell performs the play sitting down (and lip-syncing the dialogue). Leonie Z. stands at a podium, delivering a fiery lecture to students who have already canceled her. (The spare scenic design is by dots.)

Leonie Z. (Natsuko Ohama) fights back in Sam Chanse’s Disturbance Specialist (photo by Joan Marcus)

Commissioned and produced by NAATCO, Out of Time is a play for the ages. Inspired by Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s Mitten wir im Leben sind/Bach6Cellosuiten, a piece choreographed for older dancers (including De Keersmaeker herself, who is in her early sixties), Waters (Big Love, The Thin Place) gives agency to each of the actors, and each of the characters, who look back at their lives in personal ways that are poignant and gripping, especially amid a rise in anti-Asian hate crimes and during a pandemic in which nursing home deaths related to Covid-19 were seen by many as the cost of doing business as a society.

The basic conceit of the play itself is a bold act of resistance, proving that actors over sixty are fully able to present long monologues and inhabit complex characters who are a lot more than elderly grandparents ready to be put out to pasture. Each of these characters is imbued with an inner strength and purpose even as they recognize their approaching fate — and we know the same is in store for the rest of us.

“Think about death, but remember life: our long lineage,” Carla says. “Because of you, our mother, our grandmother, I am here. Today. Today I am alive. I revel in all of it.” The titular “disturbance specialist” in Leonie Z.’s lecture is a volcano mouse “that flourishes, revels, in ruined environments.” The canceled author sternly proclaims, “And in all this, what you have to tell me is that I’m not welcome. I, Leonie Z., am not welcome here, that I should go home. Delete my account. Shut up and erase myself. Roll over and quietly die?” In Out of Time, none of those are acceptable options.