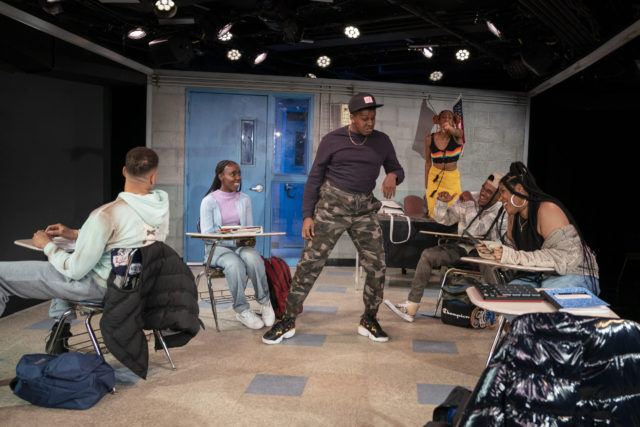

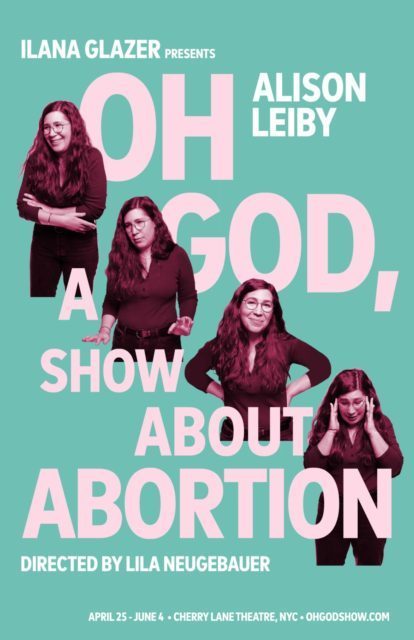

Alison Leiby shares her the details of her own abortion in comic routine at the Cherry Lane (photo by Mindy Tucker)

OH GOD, A SHOW ABOUT ABORTION

Cherry Lane Theatre

38 Commerce St.

Through June August 26, $37-$61

www.cherrylanetheatre.org

Nearly every night, the opening lines of Alison Leiby’s Oh God, a Show About Abortion change as the debate over abortion rages even hotter since May 2, when the draft opinion in which the Supreme Court appears to be ready to overturn Roe v. Wade was leaked. The day I attended, West Virginia senator Joe Manchin had announced that he would not vote for a bill to codify abortion rights, so he made it into the beginning of Leiby’s show, and not favorably.

Extended through August 26 at the Cherry Lane, Oh God is really more of a themed comedy monologue than a one-person show. For seventy-five minutes, Leiby, who has written for such series as The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel and The Opposition with Jordan Klepper, uses her recent abortion to talk about her career, her relationships with men and her family, and the need for reproductive freedom in America.

“Welcome to what my dad calls my ‘special show,’” she says. “My parents are very supportive. My mom texted me, ‘kill it tonight!’ and I’m like, I already did, that’s why the show exists.”

On an empty stage save for a mic stand, a stool, and a glass of water, the classic stand-up set, Leiby talks about “all of the unprotected sex I have had,” getting pregnant while on the road in Missouri, deciding not to keep the baby, and going to Planned Parenthood in New York City to have the procedure done. “So I had an abortion three years ago. I’m still trying to lose the no baby weight,” she explains.

She also notes, “I was thirty-five years old. I thought my eggs were just Fabergé at this point: feminine, but decorative. But this positive test brought into light all of the intense anxieties I have been feeling as a woman for years.” Many of those anxieties stem from her mother. “When I was thirty, she told me, ‘The best time in your life is when you’re married and you don’t have kids.’ I am her only child.”

Leiby uses the central narrative as the impetus to make tangential one-liners that perhaps are meant as comic relief from the main topic, but too many miss the mark or feel unnecessary, including digressions about Oreo flavors, Michael Jordan, Al Gore, Ashanti, and falafel. For comparison, in March, I saw Alex Edelman’s hysterical Just for Us, about his infiltration of a white supremacist meeting in Queens, and that was more theater than stand-up, with relevant detours about dating and family that were insightful and pushed the story forward, not one-off jokes; when he described certain events, you could see it in your mind, even though it was also an empty stage. And although Oh God credits the immensely talented Lila Neugebauer (Morning Sun, The Wolves) as director, her contributions are not clearly visible.

But the Brooklyn-based Leiby does have a lot to say about birth control, Barbie dolls, sex education in schools, period trackers, reproductive ads, doctors, Richard Gere, Jennifer Aniston, drunk sex, and womanhood in the twenty-first century. A story about receiving a nerve shot for her back is both very funny and representative of our patriarchal society. “The medical community has abandoned women,” she declares. She also delves into how “the culture seems to pit women who are mothers against women who aren’t all the time. TV shows, magazines, influencers all perpetuate this fake divide between mothers and non-mothers so we are left fighting about that while men go to space in their cock rockets? Fuck. That.”

But amid all the sociopolitical controversies and the gender gap, perhaps the most important question she asks is “If I’m not a mother, then who am I?” It’s a matter of personal choice, one that is as fraught today as it ever was, in myriad ways.

Oh God, a Show About Abortion is presented by Ilana Glazer (Broad City, The Afterparty), who, on May 22 at 7:00, will join Leiby for a conversation about the production in Buttenwieser Hall at the 92nd St. Y; in-person tickets are $30-$35, or you can watch the livestream for $20.