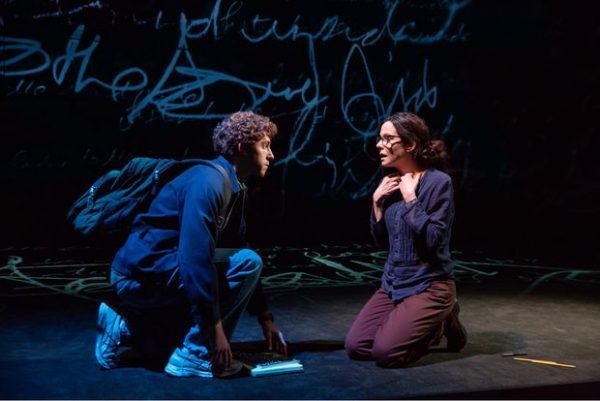

Mary Louise Parker and Will Hochman star in Adam Rapp’s The Sound Inside on Broadway (photo by Jeremy Daniel)

Studio 54

254 West 54th St.

Tuesday – Sunday through January 12, $49-$169

212-719-1300

soundinsidebroadway.com

www.lct.org

The Sound Inside is one of the most beautifully composed shows I have ever seen, an exquisitely rendered work that could have come only from the mind of an expert storyteller. Originally presented in 2018 at the Williamstown Theatre Festival and commissioned by Lincoln Center, it is written by novelist and playwright Adam Rapp, a Pulitzer Prize finalist who has authored such books as The Year of Endless Sorrows, Punkzilla, and Know Your Beholder and such plays as Red Light Winter, The Metal Children, and Blackbird, which he adapted into a 2007 film he also directed. In The Sound Inside, a luminous Mary Louise Parker stars as fifty-three-year-old Yale professor Bella Lee Baird. (Rapp has taught at the Yale School of Drama, and his mother’s maiden name is Baird.) Bella, who has written a mildly well received book, Billy Baird Runs through a Wall, alternates between telling her story in the first and third persons directly to the audience, as if narrating a novel, and participating in scenes with one of her students, the enigmatic and cynical Christopher Dunn (Will Hochman).

“A middle-aged professor of undergraduate creative writing at a prestigious Ivy League University stands before an audience of strangers,” Bella says to open the play. “She can’t quite see them but they’re out there. She can feel them — they’re as certain as old trees. Gently creaking in the heavy autumn air. Is this audience friendly, she wonders? Merciful? Are they easily distracted? Or will they hear this woman out? And what about her? Ironically, she often dissuades her students from describing a protagonist in too fine of detail. Readers only need a few telling clues.” Rapp and director David Cromer, who subtly transforms Studio 54 into an intimate classroom, follow that advice, offering only a few telling clues at a time as we excitedly hear this captivating woman out.

Christopher Dunn (Will Hochman) talks literature and more with his professor, Bella Lee Baird (Mary Louise Parker) (photo by Jeremy Daniel)

Christopher shows up at Bella’s office one day without an appointment. He has a supreme distaste for rules and regulations and eschews common decency. “Do me a favor. Next time you want to stop by without an appointment at least shoot me an email first,” she tells him. “Yeah, I don’t really do that,” he responds. They discuss Dostoyevsky, hipster baristas, and the book Christopher is writing. They strike up a friendship, but Christopher knows he is taking up a lot of her time. “I mean, if you get tired of me just say so and I can go like wander campus and get mentally prepared for the big football game coming up with Harvard this weekend,” he says. “Stockpile the coldcuts. Get my face painted. Do some steroids. Headbutt random campus bulletin boards, etcetera, etcetera.”

Bella, who’s dealing with stomach cancer and has no one else in her life, welcomes the offbeat Christopher into her daily existence. “I have no children and I’ve never been married,” she tells the audience. “Like many single, self-possessed women who’ve managed to find solid footing in the slippery foothills of higher education, I’ve been accused of being a lesbian. And a witch. And a maker of Bulgarian cheese. And a collector of cat calendars. Both my parents are dead. My father suffered a fatal heart attack at sixty-two and I’ll get to my mother in a minute. I have no brothers or sisters. I live in faculty housing. I don’t own property. I’m essentially a walking social security number with a coveted Ivy League professorship and a handful of moth-bitten sweaters.” As they grow closer, they both consider breaking down the barriers that make them each such lonely beings, committing to no one but themselves.

It’s impossible not to become instantly infatuated with Bella, so bewitchingly played by Tony, Obie, and Emmy winner Parker (Proof, Weeds). You want to just rush onstage and give her a giant hug to assure her everything will be all right, even if it won’t. Parker holds the audience in her hands, giving a tour-de-force lesson in acting. Hochman (Sweat, Dead Poets Society) is impressive in his Broadway debut, not intimidated in the least. Rapp celebrates literature without getting pedantic as he explores Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, Anne Tyler’s The Accidental Tourist, and James Salter’s Light Years. Alexander Woodward’s set features several rooms that move into the foreground and disappear into the background, superbly lit by Heather Gilbert, each one representing a different aspect of Bella’s life. Tony winner Cromer (The Band’s Visit, Our Town) keeps up a lively pace as the characters scrutinize what they are to each other.

The play refers several times to a framed photograph in Bella’s office of a “woman standing in the middle of a harvested cornfield. She’s in all black and tiny in the vast dead field,” she tells Christopher, who asks, “Is that you in the photograph? Of course it is.” But Bella says she has no idea who it is. The next time he visits her in her office, Christopher is mesmerized by the photo and asks, “Has she gotten smaller? . . . I have this weird feeling that if I come back tomorrow the field will be covered. With snow. Like twenty inches. But no footprints. The woman’s just there. As if the field imagined her.” Bella asks, “Do you think it would be a better image?” He replies, “Maybe not better. But somehow more inevitable.” It’s a fabulous moment in a fabulous play, and one that zeroes in on just who these two people are and what they want out of life.