Victor I. Cazares’s american (tele)visions takes place in a Wal-Mart that represents the United States (photo by Joan Marcus)

american (tele)visions

New York Theatre Workshop

79 East Fourth St. between Second & Third Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through October 16, $65-$75

www.nytw.org

Sitting at home watching television, you can always change the channel if you’re not enjoying a program; the same is not true when sitting in a dark theater experiencing a live play. I would have liked having a remote during Victor I. Cazares’s american (tele)visions, making its world premiere at New York Theatre Workshop through October 16.

The hundred-minute nonlinear play explores a family of illegal Mexican immigrants unable to attain the American dream. Their home base is Wal-Mart, where they are tempted by the ogre of “perpetual consumption.” When young daughter Erica (Bianca “b” Norwood), who is awaiting the rapture, admits, “I want to not want . . . to not want. I want. I don’t want to want,” it is like blasphemy.

Erica’s mother, Maria Ximena (Elia Monte-Brown), who ran away with a trucker named Stanley, explains, “We don’t watch television together anymore. And we stopped shopping together even when we were together. Yes, we would all be in the same store . . . but in different aisles, worlds apart.”

Maria’s husband, Octavio (Raúl Castillo), arrived in America first, working hard to save money to bring over the rest of his family, but he is not on a path to success. When his dead son, Alejandro (Clew), begins filming him and asks him how work is, Octavio plainly replies, “It’s fine.” Alejandro says, “Dad, that isn’t good television, you have to tell me more — something juicy.” Ocatavio offers, “I cut my hand at work today. I’m severely depressed. And I can’t stop watching television. And I think about your mom, with that fucking truck driver. And I keep thinking about you. And how I miss you.”

Projections about in world premiere at New York Theatre Workshop (photo by Joan Marcus)

Erica’s best friend and next-door neighbor is Jeremy (Ryan J. Haddad), a young gay man who spends a lot of time choosing which Barbie doll to add to his collection. Erica has promised to get him one, but she can’t afford it, so it is languishing in “Layaway Land.” Jeremy complains, “That’s no way to treat a goddess.”

Meanwhile, it is becoming apparent that Alejandro and his best friend, Jesse (Clew), were closer than just buddies, as evidenced by a VHS tape they made of themselves — a tape that Octavio wanted to destroy but the eject button on the VCR was broken and the remote control was out of batteries, overt metaphors for the father’s deteriorating life.

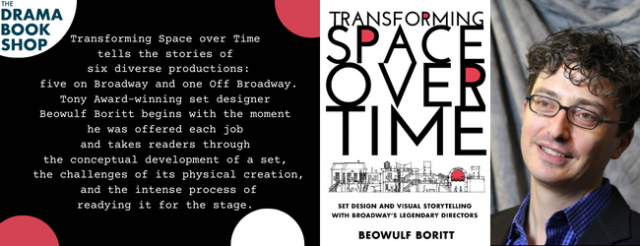

Directed by Rubén Polendo (remnant), american (tele)visions features a complex set by Bretta Gerecke that features two large rusted boxes on top of one another on either side of the stage, evoking the sculpture of Richard Serra. The boxes, on which live and prerecorded video is sometimes projected, are occasionally opened by various characters to reveal Octavio’s man cave, the Barbie section of Wal-Mart, the front of Stanley’s truck, and [.] The two angled side walls also serve as screens, showing a barrage of consumer items or the characters making confessions, which also happens in the back.

The initial wonder of the set fades, especially if you’re not near the center of the audience; various projected images and the interiors of the boxes are not fully visible to much of the audience, which was annoying. In addition, the use of the projections and boxes, as well as the dialogue and plot, grow repetitive and disappointing, as it seems like they could have done so much more with them. (The technology design is by Theater Mitu, a copresenter of the production.)

Cazares (Pinching Pennies with Penny Marshall, Ramses contra los monstruos) throws in a kitchen sink’s worth of issues, from illegal immigration, religious faith, and capitalism to queer culture, disabilities, infidelity, depression, and workplace safety, but it’s too much all at once. We watch television series because of the characters; every week the plots change, but it’s the regulars who keep us coming back, season after season. In american (tele)visions, the characters are just not compelling enough; I found myself wanting to appreciate and care about them, but they remain stagnant. And the vast array of plot points were dizzying.

By the time Maria emerged in a bizarre costume (by Mondo Guerra) as Wal-Martina, I had had enough. “Look, if they don’t like it, they can change the channel,” Maria had said earlier. But that choice was not open to me.