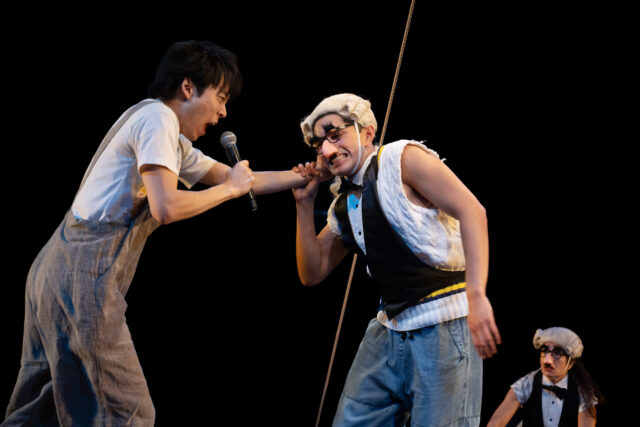

A fab cast sings and dances its way through exuberant production of The Comedy of Errors (photo by Peter Cooper)

PUBLIC THEATER MOBILE UNIT: THE COMEDY OF ERRORS

Multiple locations in all five boroughs

Through May 21, free (no RSVP necessary)

Shiva Theater, May 25 – June 11, free with RSVP

publictheater.org

Last Saturday, I did a Shakespeare doubleheader. In the afternoon, I saw the Public Theater’s Mobile Unit touring production of The Comedy of Errors, followed in the evening by NAATCO’s off-Broadway premiere of Hansol Jung’s Romeo and Juliet. The former turned out to be the most fun I’ve ever had at a Shakespeare play. The latter, by a writer whose previous show was wildly exhilarating and utterly unforgettable, started strong but couldn’t quite sustain it, ending up being not so much fun.

The Mobile Unit is now in its twelfth year of bringing free Shakespeare to all five boroughs, presenting works in prisons, shelters, and underserved community centers as well as city parks. On May 13, it pulled into the Richard Rodgers Amphitheater in Marcus Garvey Park, where part of the audience sat on the stage, on all four sides of a small, intimate square area where the action takes place; attendees could also sit in the regular seats, long concrete benches under the open sky.

Emmie Finckel’s spare set features a wooden platform and a bright yellow stepladder that serves several purposes. Lux Haac’s attractive, colorful costumes hang on racks at the back, where the actors perform quick changes. Music director and musician Jacinta Clusellas and guitarist Sara Ornelas sit on folding chairs, performing Julián Mesri’s Latin American–inspired score; Ornelas is fabulous as a troubadour and musical narrator, often wandering around the space and leading the cast in song. The lyrics, by Mesri and director and choreographer Rebecca Martínez, who collaborated on the adaptation, are in English and Spanish and are not necessarily translated word for word, but you will understand what is going on regardless of your primary tongue. As the troubadour explains, “I should mention that most of / this show will be performed in English / though it’s supposed to / take place in two states in Ancient Greece. / But don’t be surprised / if these actors switch their language.”

Trimmed down to a smooth-flowing ninety minutes, the show tells the story of a pair of twins, Dromio (Gían Pérez) and Antipholus (Joel Perez), who were separated at birth. In Ephesus, Dromio serves Antipholus, a wealthy man married to the devoted Adriana (Danaya Esperanza) but cheating on her with a lusty, demanding courtesan (Desireé Rodriguez). The other Dromio and Antipholus arrive in Ephesus and soon have everyone running around in circles as the mistaken identity slapstick ramps up.

Adriana (Danaya Esperanza) and Dromio (Gían Pérez) are all mixed up in The Comedy of Errors (photo by Peter Cooper)

Meanwhile, the merchant Egeon (Varín Ayala) is facing execution because he is from Syracuse, whose citizens are barred from Ephesus, per a decree from the Duchess Solina (Rodriguez); the goldsmith Angelo (Ayala) has made a fancy gold rope necklace for Antipholus but gives it to the wrong one; the Syracuse Dromio is confounded when Adriana’s kitchen maid claims to be his wife; the Syracuse Antipholus falls madly in love with Luciana (Keren Lugo), Adriana’s sister; and an abbess (Rodriguez) is determined to protect anyone who seeks sanctuary.

In case any or all of that is confusing, the troubadour clears things up in a series of songs that explain some, but not all, of the details, and the Public also provides everyone with a cheat sheet. Again, the troubadour: “In case you missed it / or took a little nap / Here’s what’s been happening / since we last had a chat / We’ll do our best / but we confess / this plot is really putting our skills to the test.”

It all comes together sensationally at the conclusion, as true identities are revealed, conflicts are resolved, and love wins out.

Martínez (Sancocho, Living and Breathing) fills the amphitheater with an infectious and supremely delightful exuberance. The terrific cast interacts with the audience, as if we are the townspeople of Ephesus. Gían Pérez (Sing Street) and Joel Perez (Sweet Charity, Fun Home) are hilarious as the two sets of twins, who switch hat colors to identify which brother they are at any given time. Esperanza (Mary Jane, for colored girls . . .) shines as the ever-confused, ultradramatic Adriana, Lugo (Privacy, At the Wedding) is lovely as Luciana and the duchess, Rodriguez is engaging as Emilia and the courtesan, and Ayala (The Merchant of Venice, The Taming of the Shrew) excels as Angelo, Egeon, and Dr. Pinch.

But Ornelas (A Ribbon About a Bomb, American Mariachi) all but steals the show, switching between leather and denim jackets as she portrays minor characters and plays her guitar with a huge smile on her face, words and music lifting into the air. Charles Coes’s sound design melds with the wind blowing through the trees and other people enjoying themselves in the park on a Saturday afternoon. There are no errors in this comedy.

The Mobile Unit continues on the road with stops at A.R.R.O.W. Field House and Corona Plaza in Queens and Johnny Hartman Plaza in Manhattan before heading home to the Shiva Theater at the Public for a free run May 25 through June 11.

Romeo (Major Curda) and Juliet (Dorcas Leung) have a tough time of it at Lynn F. Angelson Theater (photo by Julieta Cervantes)

ROMEO AND JULIET

Lynn F. Angelson Theater

136 East Thirteenth St. between Third & Fourth Aves.

Monday – Saturday through June 3, $40

naatco.org

In February, I called Hansol Jung’s Wolf Play at MCC “the most exhilarating hundred minutes you will spend in a theater right now.” Alas, her follow-up, a profoundly perplexing adaptation of Romeo and Juliet making its off-Broadway premiere at the Lynn F. Angelson Theater through June 3, is unable to decide whether it is a wacky farce or a serious drama, ending up as its own kind of comedy of errors.

The confusion starts as the audience enters the space, where a handmade sign says to pick one side; the stage is a circular platform cut in half by a muslin curtain. Every person stops to consider which of the two sides might be better, asking the usher and looking back and forth at the possibilities. I watched as one woman, after selecting one side, got up several times to question whether she had chosen correctly. In this case, assigned seating might have been better, or instead dividing the sections into “Montague” and “Capulet.”

The play, a collaboration between the National Asian American Theatre Company and the Oregon Shakespeare Festival’s Play On Shakespeare Project that debuted at Red Bank’s Two River Theater, begins with some funny slapstick as Daniel Liu fumbles with opening the curtains, which are tied by thick white rope to opposing scaffolds. Liu provides comic relief throughout the two-and-a-half-hour show, portraying multiple characters, including Lady Capulet in a white gown. (She’s later played by a coatrack.)

While a chorus delivers the prologue — “Two households, both alike in dignity / (In fair Verona, where we lay our scene), / From ancient grudge break to new mutiny, / Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean. / From forth the fatal loins of these two foes / A pair of star-cross’d lovers” — Capulet servants Sampson and Gregory engage in a conversation that makes sure we realize that this is not going to be a traditional production. “Gregory, I swear, man, we can’t be no one’s suckers,” Sampson says. “There’s some people I’d be happy to suck on,” Gregory responds. “Well, they can suck my cum and then succumb to my sword,” Sampson adds. The wordplay may be in the spirit of ribald Elizabethan theater, but it can feel like a pretty harsh divergence from the actual text. Jung and codirector Dustin Wills aren’t able to balance the juxtapositions as the story meanders; this adaptation assumes that the audience essentially knows what’s going to happen so necessary plot development can be skipped.

Juliet’s father has picked Count Paris (Rob Kellogg) to be her husband, but she has fallen head-over-heels for Romeo (Major Curda), scion of the Capulets’ sworn enemy, the Montagues. A swordfight between Romeo’s cousin, Mercutio (Jose Gamo), and Juliet’s cousin, Tybalt (Kellogg), lays the groundwork for more blood to follow, along with heartbreak and a classic finale that has never made complete sense.

But Jung (Wild Goose Dreams, Cardboard Piano, Human Resources) and Wills (Montag, Plano) get so caught up in theatrical hijinks — the actors climb the scaffold to operate spotlights, random props that had been tucked under the circular platform are suddenly crowding the stage, a soundboard spits out digital beats (the music is by Brian Quijada), the fourth wall is inconsistently broken — that it is hard for the audience to maintain focus and care about the characters. Junghyun Georgia Lee’s set also echoes NAATCO’s recent production of Edward Albee’s A Delicate Balance, in which rows of hundreds of glasses and books were visible underneath the stage but were not used in the play.

Peter (Daniel Liu), Potboy (Jose Gamo), and Servingman (Purva Bedi) engage in some silliness in Hansol Jung’s adaptation of Romeo and Juliet (photo by Julieta Cervantes)

The mood goes from an irreverent send-up with contemporary language to a serious interpretation using Shakespeare’s original words; it’s like Jung is unable to decide which way to go, much like the audience entering the theater. It’s a shame, because the show has its clever moments of inspiration. Mariko Ohigashi’s random costumes include Juliet’s sweatshirt that says “Abbondanza” on two lines, while Romeo’s T-shirt proclaims, “Count Your Fucking Rainbows”; Juliet wears cute and fluffy animal slippers; Friar Laurence (Purva Bedi) is dressed in oversized pants with suspenders; and Mercutio is styled like a boy band star. (However, the Groucho glasses are confounding.) Two trapdoors allow Romeo and Juliet to escape from everyone else. When things get tense, Romeo often strums a few notes on his guitar, which elicits laughter.

Even with a makeout scene, Leung (Miss Saigon, Snow in Midsummer) and Curda (KPOP!) never catch fire. Kellogg (Red Light Winter, Twelfth Night) is stalwart as Paris, Bedi (Dance Nation, India Pale Ale) is an adorable Friar Laurence, and Lee Huynh (War Horse, A Clockwork Orange) is fine as Capulet, but NAATCO cofounder Mia Katigbak (Awake and Sing, A Delicate Balance) seems to be in an alternate version of the play, Gamo (The Great Leap, The Heart of Robin Hood) overdoes it as Mercutio and Potboy, and Zion Jang is too goofy as Benvolio, while poor Liu’s (You Will Get Sick, GIRLS) shtick grows repetitive by the second act as he alternates between Lady Capulet and Peter and screams in agony a lot.

The play completely loses its already tenuous focus when Peter inexplicably insists that the musicians play “Purple Rain,” which is more than just head-scratchingly bizarre but downright annoying. It’s as if Jung and Wills were so phenomenally successful with Wolf Play that nobody wanted to just tell them no, that the Prince song makes no sense in the context of this Romeo and Juliet. Unfortunately, it’s all too representative of what ends up being a lost opportunity, a would-be comedy of too many errors.