Marc Antony (Elizabeth Marvel) bows down to Julius Caesar (Gregg Henry) in controversial Shakespeare in the Park staging (photo by Joan Marcus)

Central Park

Delacorte Theater

Through June 18, free, 8:00

shakespeareinthepark.org

In his October 14, 2016, opinion piece “Donald Trump is America’s Julius Caesar” for the Daily Caller, Moses Apostaticus wrote, “Every so often in history a man comes along who overthrows a corrupt elite and resets the political establishment. We live in such a time. In our time that man is Donald Trump.” Freelance writer Apostaticus came to praise Trump, not to bury him, explaining, “Trump’s similarities to Caesar are striking. . . . Like Caesar, Trump has become a lightning rod for the growing discontent of the American people.” In 1864, in a one-time-only benefit to raise funds for a statue of William Shakespeare to be placed in Central Park, the three Booth brothers staged the Bard’s 1599 tragedy, Julius Caesar. John Wilkes Booth wanted to play Brutus, but the meaty part went to Edwin; John played Marc Antony, while Junius portrayed Caius Cassius. John Wilkes Booth might not have gotten to stab the Roman leader onstage, but the following year he assassinated President Abraham Lincoln in Ford’s Theatre. Which brings us to Public Theater artistic director Oskar Eustis’s controversial Shakespeare in the Park version of Julius Caesar, which opened tonight at the Delacorte a day after Delta Airlines and Bank of America pulled their sponsorship of the beloved Public Theater summer series. Eustis has transformed Caesar into Trump: Gregg Henry, who portrayed Trump-like presidential contender Hollis Doyle on Scandal, wears a blue suit with an overlong red tie and is accompanied by his wife, Calpurnia (Tina Benko), who swats his hand away when he tries to hold it. Calpurnia looks and speaks like Melania but has Ivanka’s blond hair, while tribune Marullus (Natalie Woolams-Torres) resembles Trump aide Omarosa Manigault. This Caesar tweets from the bathtub, but his smart, strong right-hand woman, Marc Antony (Elizabeth Marvel), is no mere Kellyanne Conway in a track suit.

Brutus (Corey Stoll) and Cassius (John Douglas Thompson) conspire in Julius Caesar at the Delacorte (photo by Joan Marcus)

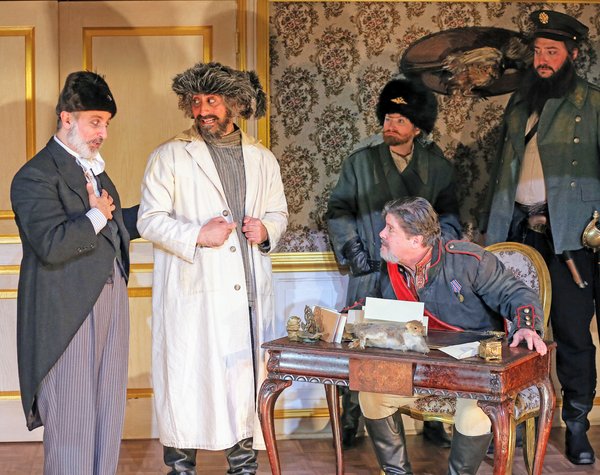

In some ways, the play recalls Orson Welles’s 1937 Mercury Theatre production, in which Caesar was based on Italian Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini ruling in modern-day Rome. Eustis sets his story in the Occupy world; before the show starts, the audience is invited up to the stage to add their views on the state of the country on a post-it and stick it onto a kind of anarchist wall. In the back of David Rockwell’s stage are three large depictions of the U.S. Capitol, a piece of the Constitution, and George Washington, along with two broken, movable sections of what could be a large crown or ancient architectural structure. The cast is dressed in contemporary clothing designed by Paul Tazewell. Caesar has just taunted the Roman rabble with the possibility he may accept their adulation and become emperor of Rome, leading a group of powerful senators — Marcus Brutus (Corey Stoll), Caius Cassius (John Douglas Thompson), Casca (Teagle F. Bougere), Decius Brutus (Eisa Davis), Cinna (Christopher Livingston), Metullus Cimber (Marjan Neshat), Trebonius (Motell Foster), and Ligarius (Chris Myers) — to bring him down in order to save the republic. So, about halfway through the intermissionless two-hour play, Caesar is brutally murdered, lying on his back as the killers wash their hands in a pool of his blood. It’s a horrifically difficult scene to watch, since Eustis is so clear that his Caesar represents Donald Trump. (A line of dialogue is even changed to include Fifth Ave., where Trump Tower is.) Like Kathy Griffin holding up an art piece of Trump’s bloodied head, Eustis has gone too far, past the bounds of thoughtful, provocative theater into a dangerous and extremely disconcerting realm. Staging such a blatant mock assassination of the president of the United States is completely unjustified and indefensible.

Brutus (Corey Stoll) addresses the people of Rome in Oskar Eustis’s adaptation of Shakespeare tragedy (photo by Joan Marcus)

Other than that, how was the play, Mrs. Lincoln? Well, in the first half, when Caesar is offstage, it is very good. The relationship between Brutus and Cassius is well developed by a calm, soft-spoken Stoll and a bold, dynamic Thompson. Nikki M. James is moving as Brutus’s concerned wife, Portia, and Nick Selting is engaging as Lucius, Brutus’s dedicated servant. Even the murder scene itself is splendidly choreographed, were it not for whom the victim represents. And once Caesar is dead, the play falls apart, and not only because of the Trump references. Marvel’s delivery of Marc Antony’s famous speech gets lost in a murmuring crowd that is dispersed throughout the Delacorte, Roman guards have been turned into evil, robotlike cops running rampant on protesters, and, for some reason, Brutus sleeps in an insipid yellow college dorm room. In a promotional statement before previews began on May 23, Eustis, who last directed Hamlet at the Delacorte in 2008, said, “Julius Caesar can be read as a warning parable to those who try to fight for democracy by undemocratic means. To fight the tyrant does not mean imitating him.” It also does not mean staging his assassination, even in the name of art.