The Heath in the McKittrick Hotel

542 West 27th St. between Tenth & Eleventh Aves.

Daily through April 20, $45

212-904-1880

mckittrickhotel.com

www.voxmotus.co.uk

Emursive productions, the innovative team that has brought such successful immersive shows as Sleep No More and The Strange Undoing of Prudencia Hart to the McKittrick Hotel in Chelsea, has done it again with Vox Motus’s Flight, a very different, much more settled kind of presentation that melds art, theater, and literature into something wholly new. The gripping story, which unfolds over about sixty tense minutes, was adapted by Oliver Emanuel from Australian journalist Caroline Brothers’s 2012 debut novel, Hinterland. For those of you who like surprises and prefer not to know anything about a show before heading to the theater, that is all I am going to tell you, other than I highly recommend it for fans of experimental, unusual methods of storytelling — you can stop right here and go get tickets now. (Also, it is definitely not for kids; no one under fourteen will be admitted.) For those of you who need to know more, read on for further details, although I strongly suggest you don’t. The primary reason I am sharing more information is to sing the praises of the people behind this unusual adventure.

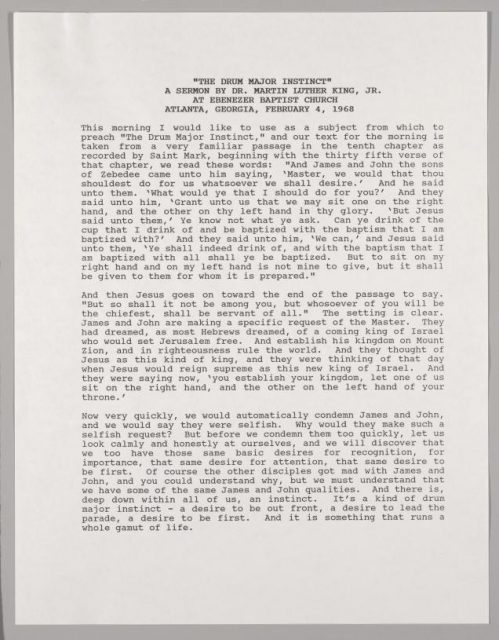

Vox Motus’s Flight can be experienced at the McKittrick Hotel through March 25 (photo by Beth Chalmers)

SPOILERS AHEAD! Entering the show takes place via a number of anteroom-type spaces: a special elevator, a coat check, a train car, and a dim, curtained space, from which theatergoers are led one-by-one into even darker private booths. Directed by Jamie Harrison and Candice Edmunds of Scottish theater company Vox Motus (The Infamous Brothers Davenport, Slick), Flight reveals itself in tiny dioramas that revolve past you on a carousel; the parade of scenarios of many shapes and sizes produces an effect similar to that of viewing graphic novel panels. The tale follows two young Afghan brothers, eight-year-old Kabir (voiced by Nalini Chertty) and fifteen-year-old Aryan (Farshid Rokey), as they flee their home country in search of freedom, a path that will take them across Europe as they encounter terrible danger, awful hardship, and moments of delight, with a third-person narrator (Emun Elliott) serving as guide. Each diorama, many of which feature the sun or the moon in the background, is designed by Harrison and Rebecca Hamilton, with tiny figures trapped in tiny rooms, forced to work on a farm, and in transit, always frightened that they will be caught. The dioramas are lit like movie sets by Simon Wilkinson, with a compelling score and sound design by Mark Melville. Part art installation, part immersive theater, Flight, the title of which refers to the brothers’ passage toward freedom as well as Kabir’s desire to fly through the air, is a timely look at what so many refugees must do to escape their violent country and find a new home, risking their life for a little bit of food and a place to sleep without fear. It’s a harrowing journey that is intelligently depicted by Vox Motus, avoiding treacly sentimentality and instead focusing on a simple narrative and the genuine peril the boys, and so many refugees and illegal immigrants around the world and in America, face on a daily basis. The production, which won a Herald Angel Award at the 2017 Edinburgh Fringe Festival, continues at the McKittrick Hotel through April 20. Don’t hesitate to get on board, while you still enjoy your own freedom.