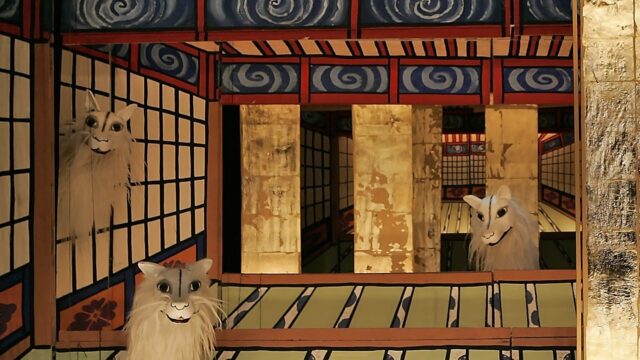

Basil Twist’s Dogugaeshi returns to Japan Society for a twentieth-anniversary encore presentation (photo © Richard Termine)

DOGUGAESHI

Japan Society

333 East 47th St. at First Ave.

September 11–19, $44-$58

212-715-1258

www.japansociety.org

basiltwist.com

Only seventy-five tickets are available to each of the twelve encore performances of Basil Twist’s Dogugaeshi at Japan Society; six shows are already sold out, so you better hurry if you want to see the special twentieth anniversary revival of the award-winning phenomenon.

Originally presented at Japan Society in 2004 in honor of the 150th anniversary of the US-Japan Treaty of Kanagawa, the sixty-minute work is part of the cultural institution’s fall 2024 series “Ningyo! A Parade of Puppetry.” Dogugaeshi (“doh-goo-guy-ih-shee”) follows the tradition of a stage mechanic developed in Japan’s Awa region using multiple painted fusuma screens and tableaux. “When I heard from several sources of a legendary eighty-eight-screen dogugaeshi, I knew that I had to do this piece with at least eighty-eight screens to bridge this all but vanished art form into the twenty-first century,” Twist, a third-generation puppeteer from San Francisco, explained in a statement.

Performed by four puppeteers including Twist, Dogugaeshi features video projections by Peter Flaherty, lighting by Andrew Hill, and sound by Greg Duffin; the score, composed by shamisen master Yumiko Tanaka, will be played live by Tanaka at the evening shows and by Yoko Reikano Kimura at the matinees. In the narrative, a white fox guides the audience through a tale of Japan’s past and present.

In the above 2014 Japan Society promotional video, Twist says that he sees Dogugaeshi, which has traveled around the globe, as a “sort of meditation into into into into into into this Japanese world. . . . The piece was created for this stage and so it really looks the best on this stage.”

“Ningyo! A Parade of Puppetry” continues October 3–5 with National Bunraku Theater, November 7–9 with “Shinnai Meets Puppetry: One Night in Winter & The Peony Lantern,” and December 12 and 13 with “The Benshi Tradition and the Silver Screen: A Japanese Puppetry Spin-off,” in which star movie talker Ichiro Kataoka and shamisen player Sumie Kaneko accompany screenings of two silent films, Daisuke Ito’s 1927 A Diary of Chuji’s Travels the first night and Shozo Makino’s 1910-17 Chushingura the second evening.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]