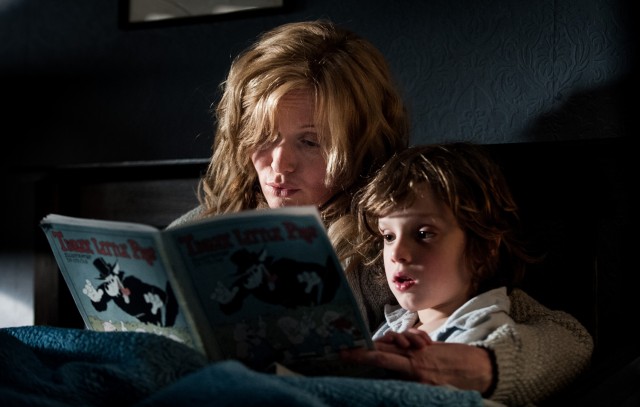

A man and his son plant a dead tree they hope will grow in Andrei Tarkovsky’s final film, The Sacrifice

THE SACRIFICE (OFFRET) (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1986)

Quad Cinema

34 West 13th St. between Fifth & Sixth Aves.

Opens Friday, October 27

212-255-2243

www.quadcinema.com

Andrei Tarkovsky’s final film, The Sacrifice, completed shortly before his death in 1986 of cancer at the age of fifty-four, serves as a glorious microcosm of his career, exploring art, faith, ritual, devotion, and humanity in uniquely cinematic ways. Made in Sweden, the film has many Bergmanesque qualities: Bergman’s longtime cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, shot the film; the production designer is Anna Asp, who won an Oscar for her work on Fanny and Alexander; Bergman’s son Daniel served as a camera assistant; and the star is Erland Josephson, who appeared in ten Bergman films as well as Tarkovsky’s previous feature, the Italy-set Nostalghia. Josephson plays Alexander, a retired professor and former actor living in the country with his wife, the cold Adelaide (Susan Fleetwood), his stepdaughter, Marta (Filippa Franzén), and young son, Little Man (Tommy Kjellqvist), who cannot speak after a recent throat operation. It is Alexander’s birthday, and the family doctor, Victor (Sven Wollter), has come to visit, along with the odd local postman, Otto (Allan Edwall), who explains, “I collect incidents. Things that are unexplainable but true.” Also on hand are the two maids, Maria (Guðrún Gísladóttir), who Otto believes is a witch, and Julia (Valérie Mairesse). Alexander states early on that he has no relationship with God, but when a nuclear holocaust threatens, he suddenly gets down on the floor and prays, offering to sacrifice whatever it takes in order for him to survive, leading to a chaotic conclusion that is part slapstick, part utter desperation.

Andrei Tarkovsky’s final film, The Sacrifice, completed shortly before his death in 1986 of cancer at the age of fifty-four, serves as a glorious microcosm of his career, exploring art, faith, ritual, devotion, and humanity in uniquely cinematic ways. Made in Sweden, the film has many Bergmanesque qualities: Bergman’s longtime cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, shot the film; the production designer is Anna Asp, who won an Oscar for her work on Fanny and Alexander; Bergman’s son Daniel served as a camera assistant; and the star is Erland Josephson, who appeared in ten Bergman films as well as Tarkovsky’s previous feature, the Italy-set Nostalghia. Josephson plays Alexander, a retired professor and former actor living in the country with his wife, the cold Adelaide (Susan Fleetwood), his stepdaughter, Marta (Filippa Franzén), and young son, Little Man (Tommy Kjellqvist), who cannot speak after a recent throat operation. It is Alexander’s birthday, and the family doctor, Victor (Sven Wollter), has come to visit, along with the odd local postman, Otto (Allan Edwall), who explains, “I collect incidents. Things that are unexplainable but true.” Also on hand are the two maids, Maria (Guðrún Gísladóttir), who Otto believes is a witch, and Julia (Valérie Mairesse). Alexander states early on that he has no relationship with God, but when a nuclear holocaust threatens, he suddenly gets down on the floor and prays, offering to sacrifice whatever it takes in order for him to survive, leading to a chaotic conclusion that is part slapstick, part utter desperation.

Although it has a more focused, direct narrative than most of Tarkovsky’s other works, The Sacrifice is far from a conventional story. Tarkovsky has written that it “is a parable. The significant events it contains can be interpreted in more than one way. . . . A great many producers eschew auteur films because they see cinema not as art but as a means of making money: the celluloid strip becomes a commodity. In that sense The Sacrifice is, amongst other things, a repudiation of commercial cinema. My film is not intended to support or refute particular ideas, or to make a case for this or that way of life. What I wanted was to pose questions and demonstrate problems that go to the very heart of our lives, and thus to bring the audience back to the dormant, parched sources of our existence. Pictures, visual images, are far better able to achieve that end than any words.” The film is filled with gorgeous visual images, beautiful shots of vast landscapes, of open doorways in stark interiors, of mirrors and windows, of Alexander and Little Man planting a dead tree by the edge of the ocean, and spoken language is often kept to a minimum, saved for philosophical discussions of God, Nietzsche, and home. Several scenes are filmed in long, continuous shots, lasting from six minutes to more than nine, heightening both the reality and the surrealism of the tale, which includes black-and-white memories, floating characters, and actors staring directly into the camera. Although Christianity plays a key role in the film — Tarkovsky considered himself a religious man, and the opening credits are shown over a close-up of Leonardo da Vinci’s “Adoration of the Magi” — the redemption that Alexander is after is a profoundly spiritual and, critically, a most human one as he searches for truth and hope amid potential annihilation. Winner of three awards at the Cannes Film Festival (among many other honors), The Sacrifice opens at the Quad on October 27 in a new 4K restoration made from the original camera negative.

We love Jimmy Stewart; we really do. Who doesn’t? But a few years ago we had the audacity to claim that Jim Parsons’s performance as Elwood P. Dowd in the 2012 Broadway revival of

We love Jimmy Stewart; we really do. Who doesn’t? But a few years ago we had the audacity to claim that Jim Parsons’s performance as Elwood P. Dowd in the 2012 Broadway revival of

FIAF’s CinéSalon series “Cinematographer Caroline Champetier: Shaping the Light” continues the celebration of the career of the César-winning French director of photography October 24 with two of her best films, Anne Fontaine’s Les Innocentes and Léos Carax’s Holy Motors, each of which will be followed by a Q&A and wine and beer reception with Champetier. Inspired by a true story, Les Innocentes is a haunting tale of a French WWII Red Cross doctor, Mathilde Beaulieu (Lou de Laâge), who is secretly summoned by Sister Maria (Agata Buzek) to help a nun give birth in a remote Polish convent. She soon discovers that several of the Benedictine nuns are pregnant, the result of brutal rapes by Soviet soldiers. The Mother Superior (Agata Kulesza) doesn’t want any outsiders to know what happened, out of both shame and fear, but the babies, and the nuns themselves, may not survive without obstetric care. Mathilde, a Communist, is stationed at a mobile surgical hospital in Warsaw, where she primarily assists Samuel (Vincent Macaigne), a Jewish doctor tending to wounded soldiers after the war, in December 1945; she gets into trouble with Samuel when she refuses to even hint at where she is disappearing to. As the due dates for the multiple births draw close, so does the danger surrounding Mathilde and the nuns.

FIAF’s CinéSalon series “Cinematographer Caroline Champetier: Shaping the Light” continues the celebration of the career of the César-winning French director of photography October 24 with two of her best films, Anne Fontaine’s Les Innocentes and Léos Carax’s Holy Motors, each of which will be followed by a Q&A and wine and beer reception with Champetier. Inspired by a true story, Les Innocentes is a haunting tale of a French WWII Red Cross doctor, Mathilde Beaulieu (Lou de Laâge), who is secretly summoned by Sister Maria (Agata Buzek) to help a nun give birth in a remote Polish convent. She soon discovers that several of the Benedictine nuns are pregnant, the result of brutal rapes by Soviet soldiers. The Mother Superior (Agata Kulesza) doesn’t want any outsiders to know what happened, out of both shame and fear, but the babies, and the nuns themselves, may not survive without obstetric care. Mathilde, a Communist, is stationed at a mobile surgical hospital in Warsaw, where she primarily assists Samuel (Vincent Macaigne), a Jewish doctor tending to wounded soldiers after the war, in December 1945; she gets into trouble with Samuel when she refuses to even hint at where she is disappearing to. As the due dates for the multiple births draw close, so does the danger surrounding Mathilde and the nuns.