Park Avenue Armory

643 Park Ave. at 67th St.

November 29 – December 4, $35, 7:30

212-933-5812

www.armoryonpark.org

www.shenweidancearts.org

Since its founding ten years ago, Shen Wei Dance Arts has been touring around the world, in traditional venues as well as unique indoor and outdoor locations. Based in New York City, SWDA has performed at the Joyce and the Lincoln Center Festival while also staging site-specific pieces for Judson Memorial Church, the Guggenheim Rotunda, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Engelhard Court, and, last fall, a two-day marathon of Re-(Part III) in Duffy Square, Grand Central Terminal, several parks, outside the New York Public Library, at Columbia, and in the 42nd St. subway station. This week they return to the Park Avenue Armory, where in 2009 artistic director Shen Wei created Behind Resonance, an exciting, involving work set in and around Ernesto Neto’s massive “Anthropodino” sculptural installation. As part of its tenth anniversary celebration, SWDA will perform 2003’s Rite of Spring (with music by Igor Stravinsky), 2000’s Folding (set to music by John Tavener along with Tibetan Buddhist chants), and the new site-specific multimedia commission Undivided Divided (scored by Sō Percussion), created specifically for the armory’s Wade Thompson Drill Hall. All choreography is by Shen Wei and lighting by Jennifer Tipton, with ten lead dancers (Cecily Campbell, Sarah Lisette Chiesa, Evan Copeland, Andrew Cowan, James Healey, Kate Jewett, Cynthia Koppe, Sara Procopio, Joan Wadopian, and Brandon Whited) and nearly two dozen additional dancers (including Shen Wei). Shen Wei favors slow, precise movement and elegant nudity, resulting in intoxicating works that lure you in with their sheer beauty. She Wei’s performances are the first of a triple play of dance at the Park Avenue Armory, followed December 14-22 by STREB’s Kiss the Air and concluding December 29-31 with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s grand finale, a series of site-specific Events that will mark the last performances ever by the noted company.

Update: As he did with Behind Resonance two years ago, New York City-based dancer-choreographer Shen Wei again turns the Park Avenue Armory’s massive Wade Thompson Drill Hall into an intimate gathering that celebrates his unique movement language, presenting two repertory works and a new site-specific piece as part of Shen Wei Dance Arts’ tenth anniversary. The evening begins with a restaging of 2003’s Rite of Spring, set to Fazil Say’s version of Stravinsky’s 1913 ballet, in which as many as sixteen dancers make their way in and around a crooked chalked grid, running to the edges, moving in formation, pausing for long moments of inactivity, and rolling on the floor, their black and gray costumes streaked with white. That is followed by 2000’s Folding, in which the dancers first appear in long red skirts and odd head extensions (evoking Robert Wilson and Matthew Barney), gliding slowly across a white reflective surface, soon evolving into duets with the performers in black, their powdered bodies folding into each other, leading to a finale that recalls, of all things, Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

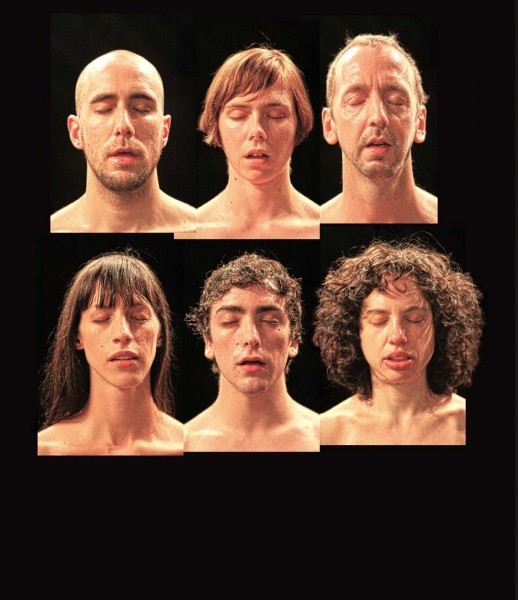

After a thirty-minute intermission in which the audience must leave the drill hall, everyone returns for the grand finale, the specially commissioned Undivided Divided, a whirlwind tour-de-force featuring thirty topless male and female dancers situated throughout the space, rolling around in paint on a long canvas, throwing themselves against the walls of a plexiglass box, climbing atop and inside a set of plastic cubes, performing intimate duets confined to a small rectangular area, amid other unique and unusual set-ups enhanced by visual projections on the floor. The audience can remain in their seats but are encouraged to remove their shoes and walk up and down pathways that allow them to come face-to-face with the dancers as they writhe about, some making eye contact, others lost in fantasy, like living sculptures in a museum. Undivided Divided is an exhilarating experience, seemingly for the dancers as much as for the crowd, an exuberant display of physicality that goes beyond mere sexuality and voyeurism, offering an energizing and thrillingly different relationship between audience and performer.