Broadway stars Dee Dee Allen (Beth Leavel) and Barry Glickman (Brooks Ashmanskas) find a common cause after their Eleanor Roosevelt musical gets panned in The Prom (photo by Deen van Meer)

THE PROM

Longacre Theatre

220 West 48th St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through October 20, $49-$169

212-239-6200

theprommusical.com

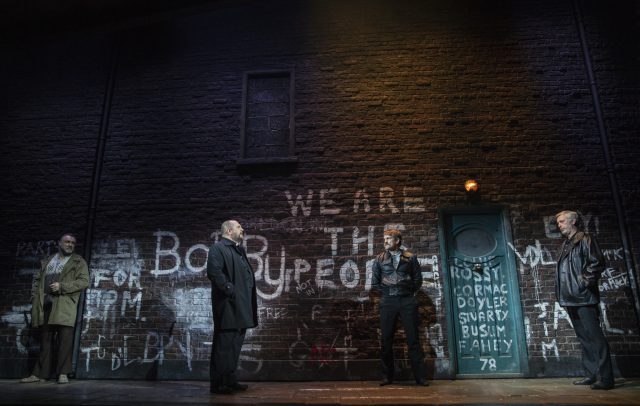

In 2012, Colorado baker Jack Phillips refused to make a wedding cake for a gay couple because of his religious beliefs, leading to a Supreme Court case and a battle with the Colorado Civil Rights Commission. In 2010, a Mississippi high school canceled its prom after being sued for barring a lesbian student from attending with her girlfriend. These two ripped-from-the-headlines situations have inspired a pair of shows currently running in the city that deal with issues of faith, prejudice, and LGBTQ rights in very different ways, both sparked by the struggle of gay couples to celebrate happy milestone events just like straight culture does. They also both explore the possibility of changing people’s minds, asking for tolerance of the intolerant. In The Prom, a musical comedy at the Longacre, the setup is theatrical: Great White Way veterans Dee Dee Allen (Beth Leavel) and Barry Glickman (Brooks Ashmanskas) are looking for a quick way to rebound from their instant flop Eleanor! — The Eleanor Roosevelt Musical by finding a cause they can support to get them some positive press attention. “People need to know it’s possible to change the world, whether you are a homely middle-aged first lady or a Broadway star,” Dee Dee, who played Eleanor, says. Barry adds, “The moment I first stepped into FDR’s shoes, and by shoes I mean wheelchair, I had an epiphany. I realized there is no difference between the president of the United States and a celebrity. We both have power. The power to change the world.”

They are joined by lesser-known minor actors Trent Oliver (Christopher Sieber) and Angie (Angie Schworer) and producer Sheldon Saperstein (Josh Lamon) and decide their best opportunity is to head to Edgewater, Indiana, where high school student Emma (Caitlin Kinnunen) is being harassed by the other students because Mrs. Greene (Courtenay Collins), the head of the PTA, has canceled the prom since Emma was going to go with another girl. Little does Mrs. Greene know that Emma is dating her daughter, Alyssa (Isabelle McCalla), who is understandably terrified of coming out to her mother. As this self-centered crackpot Justice League demands equal rights (“We’re all lesbians!”), Dee Dee unexpectedly falls for the soft-hearted, clear-sighted principal, Mr. Hawkins (Michael Potts), who takes the case to the state attorney’s office. He’s also none too happy when he begins thinking that the city folk might be in it only for the publicity, not the cause.

Angie (Angie Schworer) gets a leg up speaking with gay teen Emma Greene (Caitlin Kinnunen) (photo by Deen van Meer)

Directed and choreographed by Tony winner Casey Nicholaw (The Book of Mormon, Something Rotten!), The Prom features a book by Bob Martin and Chad Beguelin, with music by Matthew Sklar and lyrics by Beguielin, who have a blast skewering not only the concept of narcissistic celebrities but musical theater itself. It’s loaded with inside jokes; for example, when Barry says to Angie, “I thought you were in Chicago,” she replies, “I just quit. Twenty years in the chorus and they still wouldn’t let me play Roxie Hart.” Schworer played Go to Hell Kitty for three years in a tour of Chicago while also understudying the Hart role. At nearly two and a half hours, The Prom is too long and overly repetitive, and it’s pretty easy to see where it’s going as it uses a sledgehammer to bring home its sociological perspective.

Dee Dee Allen (Beth Leavel) seeks good publicity in Indiana fighting for an inclusive prom (photo by Deen van Meer)

Before leaving for Indiana, the five New Yorkers sing, “We’re gonna teach them to be more P.C. / the minute our group arrives. That’s right! Those / fist pumping / Bible thumping / Spam eating / cousin humping / cow tipping / shoulder slumping / tea bagging / Jesus jumping / losers and their inbred wives / They’ll learn compassion / and better fashion / once we at last start changing lives!” Mrs. Greene sticks to her guns, declaring, “You and your friends know nothing about us, about our town, about our people. And yet, you feel justified in telling us what to do.” It’s the privileged elitists against the deplorables, each side proclaiming that the other is the villain. The show inadvertently shoots itself in the foot by having a multiracial, color-blind cast at the school; if the town is so bigoted against gays and lesbians, it’s unlikely to be so accepting of blacks, Latinx, and Asians, so the homosexual fear/hatred feels like a plot device, which it is. Of course, the producers would have taken a different kind of hit if they had indeed hired only white actors to portray the children and adults of Edgewater. The Prom can be wacky and poignant, but it also can be preachy and predictable, whether to liberal theatergoers from the blue states or conservative tourists from red states. Nobody loses!

Della (Debra Jo Rupp) is a sweet baker who opts not to make a cake for a gay wedding in MTC production at City Center (photo © Joan Marcus, 2019)

THE CAKE

Manhattan Theatre Club

MTC at New York City Center – Stage I

Tuesday – Sunday through March 31, $89

212-581-1212

thecakeplay.com

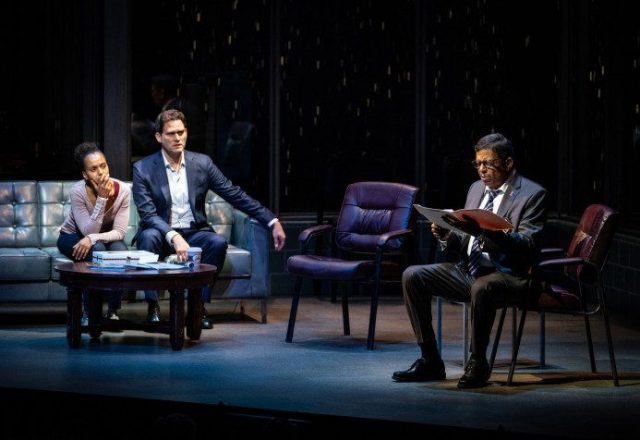

Meanwhile, Bekah Brunstetter’s The Cake, which opened this week at Manhattan Theatre Club’s Stage I at City Center, takes place in a small, tight-knit community in North Carolina, where the delightful Della (Debra Jo Rupp) runs a bakery specializing in extraordinary cakes for special occasions. Della, who is scheduled to be a contestant on The Great American Baking Show, is visited by Jen (Genevieve Angelson), the daughter of her late best friend, who has come to tell her that she is getting married and wants her to make the cake for the special event. But when Della finds out that Jen’s fiancée is Macy (Marinda Anderson), a black gluten-free Brooklynite, she changes her mind and claims that she is too busy to bake for her. While Macy is furious, Jen wants to give Della the benefit of the doubt.

When it seems that Della might be rethinking her decision (which is based on sexual orientation, not race, as Bella notes, “I don’t see color”), her husband, Tim (Dan Daily), demands that she not bake the cake because of their religion. “We know we can’t pick and choose the Bible, honey,” he explains. “That’s when the edges start to blur. Fabric starts to fray. We can be sad for her, though. We can love her, still.” Later, he says, “It’s — it’s just not natural.” Della responds, “Well, neither is confectioner’s sugar!” Tim: “You’re not making that cake.” Della: “I’ll make it if I want to.” Tim: “What’s that?” Della: “Nothing.” Tim and Della are quite a couple; she bakes delicious items that go in people’s mouths, while he, a plumber, fixes problems involving what comes out the other end.

Baker Della (Debra Jo Rupp) and plumber Tim (Dan Daily) discuss sex and religion in The Cake (photo © Joan Marcus, 2019)

Much like the Broadway elitists want to change the mind of Edgewater, Indiana, Macy feels that Jen can help Della avoid making the wrong choice. “You could change her,” Macy says. “Della? No thank you,” Jen replies. Macy: “But if you don’t push her to change, then they never will. “Jen: “They?” Macy: “All of them.” . . . Jen: All I ask is that you just try and be respectful of the people down here.” Macy: “I don’t respect these people.” Jen: “But I’m one of them.” Macy: “No you’re not.” Brunstetter, a writer and producer on the first three seasons of This Is Us who identifies as a straight white woman, was raised in a conservative North Carolina household; she loves and respects her family even though she disagrees with them on many social issues, and The Cake might her attempt to convince theatergoers who are not fond of bigots and homophobes to have more compassion and empathy for these down-home plain folk.

Della (Debra Jo Rupp) is happy for Jen (Genevieve Angelson) and Macy (Marinda Anderson) despite her religious beliefs in Bekah Brunstetter play (photo © Joan Marcus, 2019)

But it’s not that easy; no matter how cute and adorable Della is — and she’s portrayed wonderfully by Rupp, the mother on That ’70s Show and Linda on This Is Us; in fact, all four actors are terrific — it’s a lot for Brunstetter to ask of the audience. At the beginning of the play, which is engagingly directed by three-time Tony nominee Lynne Meadow (The Assembled Parties, The Tale of the Allergist’s Wife) and boasts an attractive set by John Lee Beatty that consists of ever-shifting ingredients, Della says, “See, what you have to do is really, truly follow the directions. That’s what people don’t understand.” She’s talking not only about baking but about her religion, following kitchen directions like she follows the Bible. Della also occasionally speaks with a disembodied voice from The Great American Baking Show, booming down from above as if God himself, judging if she’s worthy of being on the program. Each of the characters gets at least a little bit woke about something, resulting in a story that has tasty icing but too much fluff. “Ambivalence is just as evil as violence,” Macy argues after Della says she is not a political person, as if that excuses her from addressing the hot-button topics of the day. It’s also an excuse for Brunstetter to try to get us to accept her own family’s insensitivity to certain types of people. But being tolerant of the intolerant is not going to change things the way they need to be changed.