LIVE IDEAS 2019

New York Live Arts

219 West 19th St.

May 8-12, $10-$20

newyorklivearts.org

New York Live Arts’ seventh annual Live Ideas humanities festival explores artificial intelligence with five days of art, dance, discussion, music, lectures, and more, asking the question “AI: Are You Brave Enough for the Brave New World?” Inaugurated in 2013, the festival previously focused on Dr. Oliver Sacks and James Baldwin; social, political, artistic, and environmental issues; a nonbinary future; and strengthening democracy. Among those participating in the 2019 edition are Bill T. Jones, Nick Hallett, Yuka C Honda, Scorpion Mouse, Kyle McDonald, Patricia Marx, and Eunsu Kang, delving into technological dreaming, coding, mental illness, drones, and the truth. Tickets for most events are between ten and twenty dollars; below are some of the highlights.

Wednesday, May 8

What Is AI?, keynote/performance with Nick Hallett, Meredith Broussard, Patricia Marx, Baba Israel, and Ragamuffin, $15, 6:00

Wednesday, May 8

through

Saturday, May 11

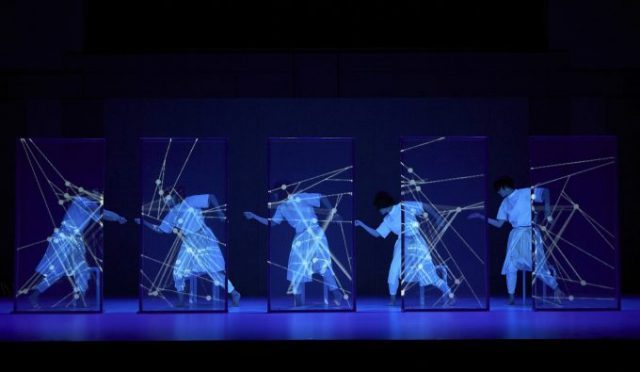

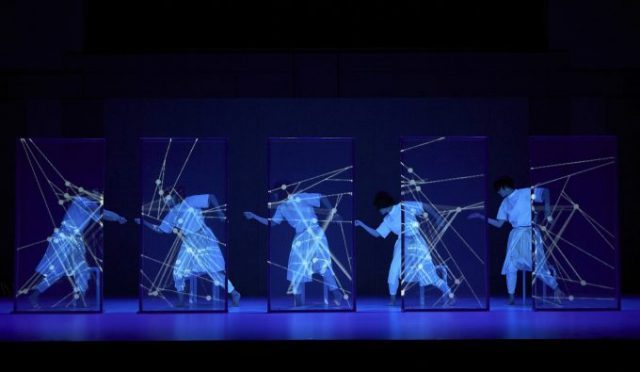

Rhizomatiks Research X ELEVENPLAY X Kyle McDonald: discrete figures, performed on stage designed for interactivity between performers, drones, and AI, $36-$45, 8:00

Thursday, May 9

Future of Work, panel discussion with Arun Sunderarajan, Matthew Putman, Carrie Gleason, Madeleine Clare Elish, and moderator Ritse Erumi, $20, 6:00

Rational Numbers: Music and AI, performance by Yuka C Honda and Angélica Negrón, $10, 9:00

Friday, May 10

Does Truth Need Defending?, panel discussion with Ambika Samarthya-Howard, Hilke Schellmann, Jeff Smith, and moderator Malika Saada Saar, $10, 6:00

Algorave: LiveCode.NYC, rave featuring AI experiments and live performances by Scorpion Mouse, CIBO + Ulysses Popple, Colonel Panix + nom de nom, ioxi + Zach Krall, and Codie, $10, 9:00

Rhizomatiks Research, ELEVENPLAY, and Kyle McDonald collaborate on interactive performance piece discrete figures (photo by Tomoya Takeshita )

Saturday, May 11

Symposium: AI x ART, including “Body, Movement, Language: AI Sketches” with Bill T. Jones, “Between Science & Speculation: Technological Dreaming” with Ani Liu, “AI in Performance: Making discrete figures” with Kyle McDonald, “Yes, AI CAN help you develop a new relationship with your audience” with Dr. Brett Ashley Crawford, “Livecoding Traversals through Sonic Spaces” with Jason Levine, “GANymedes: Art with AI” with Eunsu Kang, “Emergent Storytelling with Artificial Intelligence” with Rachel Ginsberg, and “Creating in the Age of AI” with Ani Liu, Dr. Brett Ashley Crawford, Eunsu Kang, Kyle McDonald, and Bill T. Jones, $15, 4:30

Sunday, May 12

Class: How to Question Technology, Or, What Would Neil Postman Say?, with Lance Strate, $15, 1:30

HACK-ART-THON: ACT LABS, “Breaking the Stigma Around Mental Illness,” prototype presentation, jury deliberation, and award ceremony, with Katy Gero & Anastasia Veron, Artyom Astafurov & Beth Graczyk, Jennifer Ding & Dominika Jezewska, Ishaan Jhaveri & Esther Manon Siddiquie, Keely Garfield & Cynthia Hua, Keira Heu-Jwyn Chang & Nia Laureano, Jared Katzman & Rachel Kunstadt, and Marco Berlot & Zeelie Brown, free with advance RSVP, 6:30