Paul Kos, “Sound of Ice Melting,” two twenty-five-pound blocks of ice, eight boom microphone stands, mixer, amplifier, two large speakers, and cables, 1970/2011 (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

Bronx Museum of the Arts

1040 Grand Concourse at 165th St.

Thursday – Sunday through September 8, free, 11:00 am – 6:00 (8:00 on Fridays)

718-681-6000

www.bronxmuseum.org

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, a group of West Coast artists developed an evolving brand of California Conceptualism that incorporated environmental concerns and social interaction into works that explored consumer culture and the changing political landscape with a wry sense of humor while redefining what art is and could be. Originally mounted as part of the Getty Foundation’s Pacific Standard Time series, “State of Mind: New California Art Circa 1970” continues at the Bronx Museum of the Arts through September 8, comprising approximately 150 paintings, drawings, photographs, video, performances, and installation from 60 artists. Curators Constance Lewallen and Karen Moss have arranged the splendidly designed exhibit into such thematic sections as “The Street,” “Public and Private Space,” “The Body and Performance,” “Language and Wordplay,” and “Feminism and Domestic Space,” offering an exciting, well-paced tour of a California avant-garde immersed in the counterculture revolution of the era.

Visitors are encouraged to walk through Barbara T. Smith’s “Field Piece” and trip the light fantastic (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

For “Hair Transplant,” Nancy Buchanan exchanged body hair with Robert Walker. For “California Map Project,” John Baldessari spelled out the name of the state using geographic formations. Visitors can walk into Bruce Nauman’s immersive “Yellow Room (Triangular)” and prance through Barbara T. Smith’s “Field Piece,” lighting up nine-foot-tall blades of grass made of translucent resin. For her “Sitting Still” series, Bonnie Sherk took a seat in public places as people passed her by. Lowell Darling offers visitors a diploma from the Fat City School of Finds Art. Allen Ruppersberg Sunset Boulevard “Al’s Grand Hotel” is partially re-created, a 1971 project in which people could actually rent rooms and become part of the art. One of the highlights of the exhibit is a trio of video monitors showing cutting-edge, experimental short films by Chris Burden, Paul McCarthy, and Nauman that subvert the traditional nature of the creative process. For “Sound of Ice Melting,” Paul Kos surrounds a block of ice with eight microphones, which make the ice a kind of celebrity with not a whole lot to say. Other artists featured in the show are William Wegman, Martha Rosler, Ed Ruscha, Lynn Hershman, David Hammons, Eleanor Antin, Terry Fox, Allan Kaprow, and Bas Jan Ader, who literally died for his art. Although State of Mind” is a snapshot of a very specific period in the history of twentieth-century American art, it also reveals how these conceptualists not only captured the zeitgeist of the times but opened a wide artistic path for the future. The Bronx Museum is open Thursday through Sundays, and admission is always free. This week’s First Fridays program features live performances and special screenings from participants in the “Bronx Calling” Second AIM Biennial, which consists of works by such emerging New York area artists as Allison Wall, Diana Shpungin, Alejandro Guzmán, Daniele Genadry, and Alan and Michael Fleming. The evening will include Katie Cercone’s ritual-based “Queen$ Domin8tin,” Alicia Grullon’s “Cold War Karaoke Night” in which the audience can reenact cold war speeches, and the Flemings’ “Objects and Extensions,” a dance piece in which the brothers integrate their bodies into the architecture of the museum.

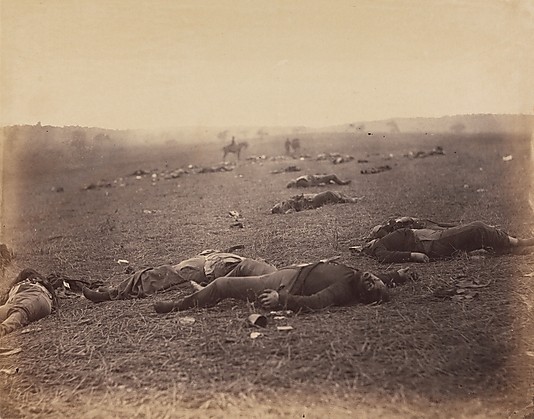

![Unknown, “[Captain Charles A. and Sergeant John M. Hawkins, Company E, ‘Tom Cobb Infantry,’ Thirty-eighth Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry],” ambrotype, 1861-62 (David Wynn Vaughan Collection)](https://twi-ny.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/photography-american-civil-war-e1377517263437.jpg)