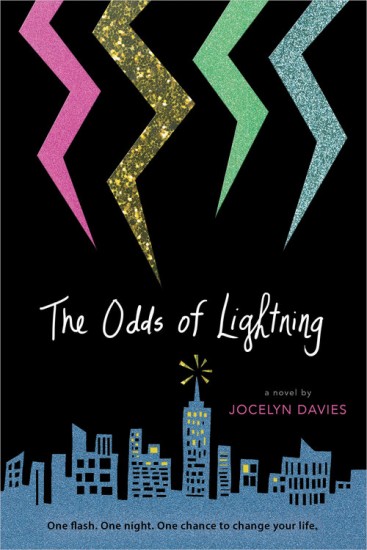

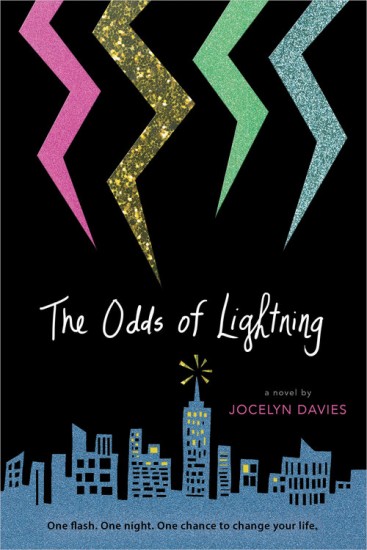

Jocelyn Davies will be at McNally Jackson on September 20 for launch party of her latest novel, THE ODDS OF LIGHTNING

McNally Jackson

52 Prince St. between Lafayette & Mulberry Sts.

Tuesday, September 20, free, 7:00

212-274-1160

www.mcnallyjackson.com

www.jocelyndavies.com

Children’s book editor and author Jocelyn Davies is one of the most upbeat, happy people you’re ever likely to meet. She’s always quick with a smile and a note of encouragement, sharing her positivity and funny sense of humor with all around her. I’ve had the privilege of being around her for several years now, working with her at HarperCollins Children’s Books, where she edits young adult novels in addition to having written the trilogy A Beautiful Dark, A Fractured Light, and A Radiant Sky. Her latest YA novel, The Odds of Lightning (Simon Pulse, September 20, $17.99), was just listed by BuzzFeed as number 6 on its list of “23 YA Books You Need to Read This Fall.” The story follows four high school friends who develop special powers when the roof they are standing on gets struck by lightning, but this is no mere update of the Fantastic Four; instead, their powers stem from common fears that are deep within them, and us. As she prepared for the September 20 book launch of The Odds of Lightning at McNally Jackson, Jocelyn took the time to answer some questions about writing and editing YA novels, facing one’s fears, and living it up in New York City, where she was born and raised.

twi-ny: You’ve never been struck by lightning yourself. Is it a particular fear of yours? Or maybe you have a special relationship with storms since you experienced a blizzard in Central Park when you were still in utero?

Jocelyn Davies: Ha! Maybe I do! Or maybe I have a special relationship to Central Park, since many scenes in the book take place there!

I’ve never been struck by lightning — but one time, I almost was! When I was a teenager, I was hiking in Colorado when a storm rolled in very suddenly. It was pouring, and there was intense lightning and thunder, and we were up on a mountain, which is not a good place to be during a thunder and lightning storm. The group I was with basically flew down the mountain to base camp as quickly as we could, with lightning flashing all around us. Memory and imagination may have intensified the experience in retrospect, but I remember dodging actual lightning bolts (just like the kids in The Odds of Lightning when they’re riding their Citi Bikes across town).

twi-ny: Yikes!

jd: I guess the appeal of lightning is that it has this sort of mythical, rare quality. It’s beautiful but dangerous, is a pretty regular occurrence in nature, but it’s rarer to be struck. There’s something magical about it, which made it the perfect catalyst to kick-start the adventure in this book. It takes place on a literal “dark and stormy night.”

twi-ny: About seven years ago, I was electrocuted in a thunderstorm at an outdoor concert, and the shock actually led to some psychological benefits, although no superpowers, like the four main characters in the book receive. If you could choose any superpower for yourself, what would it be?

jd: I want to hear more about these psychological benefits! I’ve given this a lot of thought, and right now I would want the ability to teleport anywhere in the blink of an eye. I could visit my friends across the country whenever I wanted, travel to all the places on my international bucket list — even the really far places like Australia and Japan — as easily as walking down the block, avoid the subway rush hour commute, and I’d never be late!

twi-ny: I’m not sure even teleportation could help you avoid a New York City rush hour. The superpowers the protagonists get focus on important problems that most teenagers go through, primarily involving self-identity and trying to find one’s place in the world. Do you relate to any one character more than the others? I’m thinking it might actually be Juliet.

jd: Well, I did study theater in high school and college, like Juliet (and Lu). But on some level I’ve been a bit of all four of the main characters, at various points in my life, and I have this hunch that a lot of readers might feel that way too. I think most people go through phases where they question who they are, hold back from going for what they really want, fear getting hurt, and feel invisible. Tiny, Lu, Nathaniel, and Will’s stories are specific to their unique characters, but they also have a somewhat universal quality.

twi-ny: What was your biggest fear in high school? What is it now?

jd: I remember feeling like everything was always changing, that you couldn’t really trust or rely on anything, that even if things were going great one day, the rug could be pulled out from you the next. In the book, Tiny loves this line from The Great Gatsby about “the unreality of reality,” and the rock of the world being founded securely on a fairy’s wing. And that’s how I felt a lot of the time, that tectonic plates were always shifting beneath me, that nothing would ever stay the way it was — and that was scary. I probably relate to Tiny more now — that feeling of wanting to be heard and understood.

twi-ny: That never does go away, does it. With the stormpocalypse approaching, the high school students decide to have a blowout party, even with the SATs scheduled for the next day. Early on, you ask the question, “If it were the end of the world, would you stay at home?” What would you do if you knew that the end of the world was coming?

jd: I’d definitely spend it with my family and friends! And maybe go skydiving or cliff jumping. I would not stay at home — I’d be having one last adventure.

twi-ny: That might be a bit too adventurous for me. During the day, you’re an editor at HarperCollins Children’s Books, for whom you’ve previously written a YA trilogy. Is it hard to balance the two very different skills, writing and editing?

jd: I’ve learned a lot about the process of crafting a novel from working with so many talented writers and editors over the years. I learn new skills and lessons all the time while editing other writers’ books, and I’ve learned things from my own editors that I pass on to writers I work with. It’s a pretty symbiotic relationship. Writing and editing are two very different parts of the brain — you can’t really use both at the same time. Writing is boundless — you do a lot of experimenting, letting your imagination run wild, trying new things and seeing what works. Editing is about reining in, taking all that raw material and helping shape it into a story with a beginning, middle, and end, consistent characters, satisfying emotional arc, logical world rules. But at the end of the day, they’re both working toward the same end goal.

Things are looking up for YA author Jocelyn Davies with release of THE ODDS OF LIGHTNING

twi-ny: If you ever have free time to read something for yourself, what types of genres do you turn to? Or are you pretty much wrapped up in YA all the time?

jd: Sometimes I feel like I eat, sleep, and breathe YA. At any given time, I’m immersed in the world of what I’m writing, am reading a submission or a work-in-progress manuscript, and am reading a recently released YA novel. When I go on vacation and I’m looking for something to take me out of the YA world for a little bit, I gravitate toward literary fiction, humorous essays, and, lately, a good page-turning literary thriller.

twi-ny: You were born and raised in New York, and you currently live in Brooklyn and work in Manhattan. New York City is like a character unto itself in The Odds of Lightning. What are some of your favorite parts of the city?

jd: A lot of them — like Central Park, and the American Museum of Natural History — are featured in the book. Ice skating at Wollman Rink in the middle of Central Park makes you feel like a character in a New York City romantic comedy. I love the rich historic feel of the Upper West Side, the West Village, brownstone Brooklyn — places where stories were taking place long before I was born. Driving across the Brooklyn Bridge in a taxi with the windows down fills me with love for New York, every time. It always makes me feel like I’m home.

twi-ny: The launch party for The Odds of Lightning is taking place September 20 at McNally Jackson. What’s on the agenda?

jd: I’ll be having a conversation with children’s book buyer Cristin Stickles, reading from The Odds of Lightning, signing books — and maybe there will be some fun surprises!

![Vanda Vieira-Schmidt Weltrettungsprojekt [World Rescue Project] consists of more than thirty thousand drawings (photo by Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio)](https://twi-ny.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/the-keeper-2-e1474394670620.jpg)

Sandrine Bonnaire won the César for Most Promising Actress in her film debut, Maurice Pialat’s À nos amours, and she has more than fulfilled that promise in her still-vibrant thirty-plus-year career. Bonnaire stars as fifteen-year-old Suzanne, who suddenly becomes sexually promiscuous one summer. “‘Don’t you think one can die of love?’” she asks, rehearsing for a camp play. “‘You told me you loved me. What kind of a world is this?’” As Suzanne flits about from lover to lover, her family begins to notice a change in her and is not very happy about it. Her mother (Evelyne Ker) and father (Pialat) are on the verge of a breakup, and her creepy brother, Robert (Dominique Besnehard), doesn’t really get any of it; all three seem emotionally stunted, able only to express their feelings about Suzanne’s behavior by striking her physically. Suzanne is a decidedly contemporary Western European ingénue; the film casts no aspersions on her and does not judge her actions, even if her mother and Robert do. Bonnaire was around the same age as her character when she made the film, which contains significant nudity and bed scenes if not graphic depictions of sex; the film would likely have been wildly controversial if made in Hollywood with a fifteen-year-old American actress. Suzanne’s father, a furrier who has left his wife for another woman, is sad that she has lost one of her dimples, a sign of her maturing; when she was a baby, he wanted to protect her from kidnapping, but now he knows and accepts that he no longer has control over her life. Suzanne enjoys the sex she is having but is obviously seeking something more; but Pialat, the director of the film and who also plays the fictional father, never delves too deeply into her psyche, refusing to provide any easy answers or simplistic resolutions for this complex coming-of-age story.

Sandrine Bonnaire won the César for Most Promising Actress in her film debut, Maurice Pialat’s À nos amours, and she has more than fulfilled that promise in her still-vibrant thirty-plus-year career. Bonnaire stars as fifteen-year-old Suzanne, who suddenly becomes sexually promiscuous one summer. “‘Don’t you think one can die of love?’” she asks, rehearsing for a camp play. “‘You told me you loved me. What kind of a world is this?’” As Suzanne flits about from lover to lover, her family begins to notice a change in her and is not very happy about it. Her mother (Evelyne Ker) and father (Pialat) are on the verge of a breakup, and her creepy brother, Robert (Dominique Besnehard), doesn’t really get any of it; all three seem emotionally stunted, able only to express their feelings about Suzanne’s behavior by striking her physically. Suzanne is a decidedly contemporary Western European ingénue; the film casts no aspersions on her and does not judge her actions, even if her mother and Robert do. Bonnaire was around the same age as her character when she made the film, which contains significant nudity and bed scenes if not graphic depictions of sex; the film would likely have been wildly controversial if made in Hollywood with a fifteen-year-old American actress. Suzanne’s father, a furrier who has left his wife for another woman, is sad that she has lost one of her dimples, a sign of her maturing; when she was a baby, he wanted to protect her from kidnapping, but now he knows and accepts that he no longer has control over her life. Suzanne enjoys the sex she is having but is obviously seeking something more; but Pialat, the director of the film and who also plays the fictional father, never delves too deeply into her psyche, refusing to provide any easy answers or simplistic resolutions for this complex coming-of-age story.

Nominated for the Palme d’Or and a Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, My Night at Maud’s, Éric Rohmer’s fourth entry in his Six Moral Tales series (falling between La Collectionneuse and Claire’s Knee) continues the French director’s fascinating exploration of love, marriage, and tangled relationships. Three years removed from playing the romantic racecar driver Jean-Louis in Claude Lelouch’s A Man and a Woman, Jean-Louis Trintignant again stars as a man named Jean-Louis, this time a single thirty-four-year-old Michelin engineer living a relatively solitary life in the French suburb of Clermont. A devout Catholic, he is developing an obsession with a fellow churchgoer, the blonde, beautiful Françoise (Marie-Christine Barrault), about whom he knows practically nothing. After bumping into an old school friend, Vidal (Antoine Vitez), the two men delve into deep discussions of religion, Marxism, Pascal, mathematics, Jansenism, and women. Vidal then invites Jean-Louis to the home of his girlfriend, Maud (Françoise Fabian), a divorced single mother with open thoughts about sexuality, responsibility, and morality that intrigue Jean-Louis, for whom respectability and appearance are so important. The conversation turns to such topics as hypocrisy, grace, infidelity, and principles, but Maud eventually tires of such talk. “Dialectic does nothing for me,” she says shortly after explaining that she always sleeps in the nude. Later, when Jean-Louis and Maud are alone, she tells him, “You’re both a shamefaced Christian and a shamefaced Don Juan.” Soon a clearly conflicted Jean-Louis is involved in several love triangles that are far beyond his understanding, so he again seeks solace in church. My Night at Maud’s is a classic French tale, with characters spouting off philosophically while smoking cigarettes, drinking wine and other cocktails, and getting naked. Shot in black-and-white by Néstor Almendros, the film roams from midnight mass to a single woman’s bed and back to church, as Jean-Louis, played with expert concern by Trintignant, is forced to examine his own deep desires and how they relate to his spirituality. Fabian (Belle de Jour, The Letter) is outstanding as Maud, whose freedom titillates and confuses Jean-Louis. My Night at Maud’s, which is being shown September 17-18 and 24-25 as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s Six Moral Tales series, is one of Rohmer’s best, most accomplished works despite its haughty intellectualism.

Nominated for the Palme d’Or and a Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, My Night at Maud’s, Éric Rohmer’s fourth entry in his Six Moral Tales series (falling between La Collectionneuse and Claire’s Knee) continues the French director’s fascinating exploration of love, marriage, and tangled relationships. Three years removed from playing the romantic racecar driver Jean-Louis in Claude Lelouch’s A Man and a Woman, Jean-Louis Trintignant again stars as a man named Jean-Louis, this time a single thirty-four-year-old Michelin engineer living a relatively solitary life in the French suburb of Clermont. A devout Catholic, he is developing an obsession with a fellow churchgoer, the blonde, beautiful Françoise (Marie-Christine Barrault), about whom he knows practically nothing. After bumping into an old school friend, Vidal (Antoine Vitez), the two men delve into deep discussions of religion, Marxism, Pascal, mathematics, Jansenism, and women. Vidal then invites Jean-Louis to the home of his girlfriend, Maud (Françoise Fabian), a divorced single mother with open thoughts about sexuality, responsibility, and morality that intrigue Jean-Louis, for whom respectability and appearance are so important. The conversation turns to such topics as hypocrisy, grace, infidelity, and principles, but Maud eventually tires of such talk. “Dialectic does nothing for me,” she says shortly after explaining that she always sleeps in the nude. Later, when Jean-Louis and Maud are alone, she tells him, “You’re both a shamefaced Christian and a shamefaced Don Juan.” Soon a clearly conflicted Jean-Louis is involved in several love triangles that are far beyond his understanding, so he again seeks solace in church. My Night at Maud’s is a classic French tale, with characters spouting off philosophically while smoking cigarettes, drinking wine and other cocktails, and getting naked. Shot in black-and-white by Néstor Almendros, the film roams from midnight mass to a single woman’s bed and back to church, as Jean-Louis, played with expert concern by Trintignant, is forced to examine his own deep desires and how they relate to his spirituality. Fabian (Belle de Jour, The Letter) is outstanding as Maud, whose freedom titillates and confuses Jean-Louis. My Night at Maud’s, which is being shown September 17-18 and 24-25 as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s Six Moral Tales series, is one of Rohmer’s best, most accomplished works despite its haughty intellectualism.