Iranian auteur Jafar Panahi plays himself in gorgeously photographed and beautifully paced 3 Faces

3 FACES (SE ROKH) (Jafar Panahi, 2018)

IFC Center

323 Sixth Ave. at West Third St.

Opens Friday, March 8

212-924-7771

www.ifccenter.com

One of the most brilliant and revered storytellers in the world, Iranian auteur Jafar Panahi proves his genius yet again with his latest cinematic masterpiece, the tenderhearted yet subtly fierce road movie 3 Faces. The film, which made its US premiere this past fall at the New York Film Festival, won the Best Screenplay prize at Cannes, and screened in January as part of IFC’s inaugural Iranian Film Festival New York, is now back at IFC for a theatrical run beginning March 8. As with some of Panahi’s earlier works, 3 Faces walks the fine line between fiction and nonfiction while defending the art of filmmaking. Popular Iranian movie and television star Behnaz Jafari, playing herself, has received a video in which a teenage girl named Marziyeh (Marziyeh Rezaei), frustrated that her family will not let her study acting at the conservatory where she’s been accepted, commits suicide onscreen, disappointed that her many texts and phone calls to her hero, Jafari, went unanswered. Deeply upset by the video — which was inspired by a real event — Jafari, who claims to have received no such messages, enlists her friend and colleague, writer-director Panahi, also playing himself, to head into the treacherous mountains to try to find out more about Marziyeh and her friend Maedeh (Maedeh Erteghaei). They learn the girls are from a small village in the Turkish-speaking Azeri region in northwest Iran, and as they make their way through narrow, dangerous mountain roads, they encounter tiny, close-knit communities that still embrace old traditions and rituals and are not exactly looking to help them find out the truth.

One of the most brilliant and revered storytellers in the world, Iranian auteur Jafar Panahi proves his genius yet again with his latest cinematic masterpiece, the tenderhearted yet subtly fierce road movie 3 Faces. The film, which made its US premiere this past fall at the New York Film Festival, won the Best Screenplay prize at Cannes, and screened in January as part of IFC’s inaugural Iranian Film Festival New York, is now back at IFC for a theatrical run beginning March 8. As with some of Panahi’s earlier works, 3 Faces walks the fine line between fiction and nonfiction while defending the art of filmmaking. Popular Iranian movie and television star Behnaz Jafari, playing herself, has received a video in which a teenage girl named Marziyeh (Marziyeh Rezaei), frustrated that her family will not let her study acting at the conservatory where she’s been accepted, commits suicide onscreen, disappointed that her many texts and phone calls to her hero, Jafari, went unanswered. Deeply upset by the video — which was inspired by a real event — Jafari, who claims to have received no such messages, enlists her friend and colleague, writer-director Panahi, also playing himself, to head into the treacherous mountains to try to find out more about Marziyeh and her friend Maedeh (Maedeh Erteghaei). They learn the girls are from a small village in the Turkish-speaking Azeri region in northwest Iran, and as they make their way through narrow, dangerous mountain roads, they encounter tiny, close-knit communities that still embrace old traditions and rituals and are not exactly looking to help them find out the truth.

Iranian star Behnaz Jafari plays herself as she tries to solve a mystery in Jafar Panahi’s 3 Faces

Panahi (Offside, The Circle) — who is banned from writing and directing films in his native Iran, is not allowed to give interviews, and cannot leave the country — spends much of the time in his car, which not only works as a plot device but also was considered necessary in order for him to hide from local authorities who might turn him in to the government. He and Jafari stop in three villages, the birthplaces of his mother, father, and grandparents, for further safety. The title refers to three generations of women in Iranian cinema: Marziyeh, the young, aspiring artist; Jafari, the current star (coincidentally, when she goes to a café, the men inside are watching an episode from her television series); and Shahrzad, aka Kobra Saeedi, a late 1960s, early 1970s film icon who has essentially vanished from public view following the Islamic Revolution of 1978-79, banned from acting in Iran. (Although Shahrzad does not appear as herself in the film, she does read her poetry in voiceover.) 3 Faces is gorgeously photographed by Amin Jafari and beautifully edited by Mastaneh Mohajer, composed of many long takes with few cuts and little camera movement; early on there is a spectacular eleven-minute scene in which an emotionally tortured Jafari listens to Panahi next to her on the phone, gets out of the car, and walks around it, the camera glued to her the whole time in a riveting tour-de-force performance.

Behnaz Jafari and Jafar Panahi encounter culture clashes and more in unique and unusual road movie

3 Faces is Panahi’s fourth film since he was arrested and convicted in 2010 for “colluding with the intention to commit crimes against the country’s national security and propaganda against the Islamic Republic”; the other works are This Is Not a Film, Closed Curtain, and Taxi Tehran, all of which Panahi starred in and all of which take place primarily inside either a home or a vehicle. 3 Faces is the first one in which he spends at least some time outside, where it is more risky for him; in fact, whenever he leaves the car in 3 Faces, it is evident how tentative he is, especially when confronted by an angry man. The film also has a clear feminist bent, not only centering on the three generations of women, but also demonstrating the outdated notions of male dominance, as depicted by a stud bull with “golden balls” and one villager’s belief in the mystical power of circumcised foreskin and how he relates it to former macho star Behrouz Vossoughi, who appeared with Shahrzad in the 1973 film The Hateful Wolf and is still active today, living in California. Panahi, of course, will not be present for the opening at IFC, as his road has been blocked, leaving him a perilous path that he must navigate with great care.

Award-winning Haitian filmmaker Raoul Peck’s Fatal Assistance begins by posting remarkable numbers onscreen: In the wake of the devastating earthquake that hit his native country on January 12, 2010, there were 230,000 deaths, 300,000 wounded, and 1.5 million people homeless, with some 4,000 NGOs coming to Haiti to make use of a promised $11 billion in relief over a five-year period. But as Peck reveals, there is significant controversy over where the money is and how it’s being spent as the troubled Haitian people are still seeking proper health care and a place to live. “The line between intrusion, support, and aid is very fine,” says Jean-Max Bellerive, the Haitian prime minister at the time of the disaster, explaining that too many of the donors want to cherry-pick how their money is used. Bill Vastine, senior “debris” adviser for the Interim Commission for the Reconstruction of Haiti (CIRH), which was co-chaired by Bellerive and President Bill Clinton, responds, “The international community said they were gonna grant so many billions of dollars to Haiti. That didn’t mean we were gonna send so many billions of dollars to a bank account and let the Haitian government do with it as they will.” Somewhere in the middle is CIRH senior housing adviser Priscilla Phelps, who seems to be the only person who recognizes why the relief effort has turned into a disaster all its own; by the end of the film, she is struggling to hold back tears.

Award-winning Haitian filmmaker Raoul Peck’s Fatal Assistance begins by posting remarkable numbers onscreen: In the wake of the devastating earthquake that hit his native country on January 12, 2010, there were 230,000 deaths, 300,000 wounded, and 1.5 million people homeless, with some 4,000 NGOs coming to Haiti to make use of a promised $11 billion in relief over a five-year period. But as Peck reveals, there is significant controversy over where the money is and how it’s being spent as the troubled Haitian people are still seeking proper health care and a place to live. “The line between intrusion, support, and aid is very fine,” says Jean-Max Bellerive, the Haitian prime minister at the time of the disaster, explaining that too many of the donors want to cherry-pick how their money is used. Bill Vastine, senior “debris” adviser for the Interim Commission for the Reconstruction of Haiti (CIRH), which was co-chaired by Bellerive and President Bill Clinton, responds, “The international community said they were gonna grant so many billions of dollars to Haiti. That didn’t mean we were gonna send so many billions of dollars to a bank account and let the Haitian government do with it as they will.” Somewhere in the middle is CIRH senior housing adviser Priscilla Phelps, who seems to be the only person who recognizes why the relief effort has turned into a disaster all its own; by the end of the film, she is struggling to hold back tears.

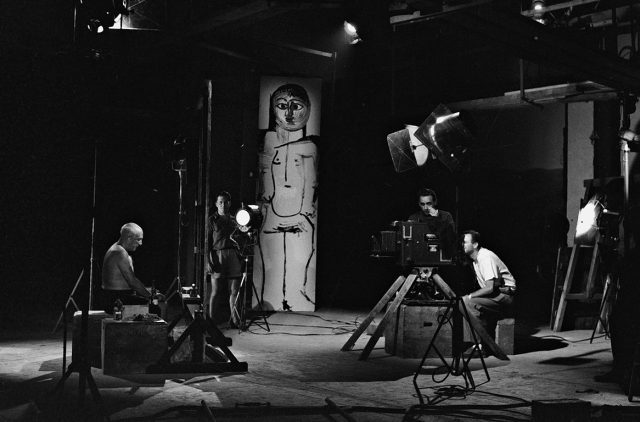

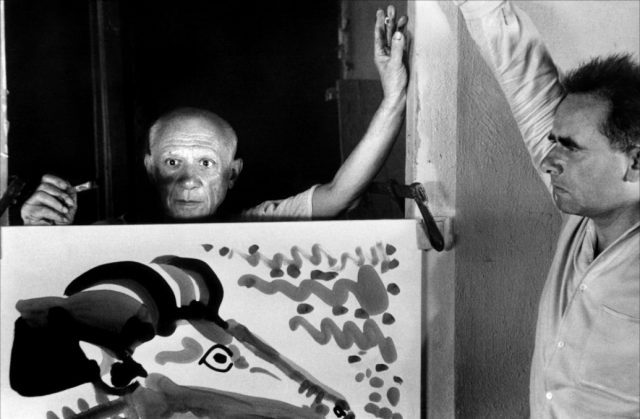

Suspense master Henri-Georges Clouzot’s The Mystery of Picasso, now playing at Film Forum in a beautiful 4K restoration from Milestone, is one of the most thrilling films ever made about art and the creative process. In the 1949 short Visit to Picasso, Belgian director Paul Haesaerts photographed Pablo Picasso painting on a glass plate. Picasso and his longtime friend Clouzot take that basic concept to the next level in The Mystery of Picasso, in which the Spanish artist uses inks that bleed through paper so Clouzot can shoot him from the other side; the works unfold like magic, evolving on camera seemingly without the genius present. “We’d give anything to have been in Rimbaud’s mind while he was writing ‘Le Bateau Ivre,’ or in Mozart’s while he was composing the Jupiter Symphony, to discover this secret mechanism that guides the creator in a perilous adventure,” Clouzot says at the beginning. “Thanks to God, what is impossible in poetry and music is attainable in painting. To find out what goes on in a painter’s head, you need to follow his hand. A painter’s adventure is an odd one!” It’s breathtaking as the pictures emerge, revealing Picasso’s remarkable command of line, altering images as he pleases with just a brushstroke or two.

Suspense master Henri-Georges Clouzot’s The Mystery of Picasso, now playing at Film Forum in a beautiful 4K restoration from Milestone, is one of the most thrilling films ever made about art and the creative process. In the 1949 short Visit to Picasso, Belgian director Paul Haesaerts photographed Pablo Picasso painting on a glass plate. Picasso and his longtime friend Clouzot take that basic concept to the next level in The Mystery of Picasso, in which the Spanish artist uses inks that bleed through paper so Clouzot can shoot him from the other side; the works unfold like magic, evolving on camera seemingly without the genius present. “We’d give anything to have been in Rimbaud’s mind while he was writing ‘Le Bateau Ivre,’ or in Mozart’s while he was composing the Jupiter Symphony, to discover this secret mechanism that guides the creator in a perilous adventure,” Clouzot says at the beginning. “Thanks to God, what is impossible in poetry and music is attainable in painting. To find out what goes on in a painter’s head, you need to follow his hand. A painter’s adventure is an odd one!” It’s breathtaking as the pictures emerge, revealing Picasso’s remarkable command of line, altering images as he pleases with just a brushstroke or two.