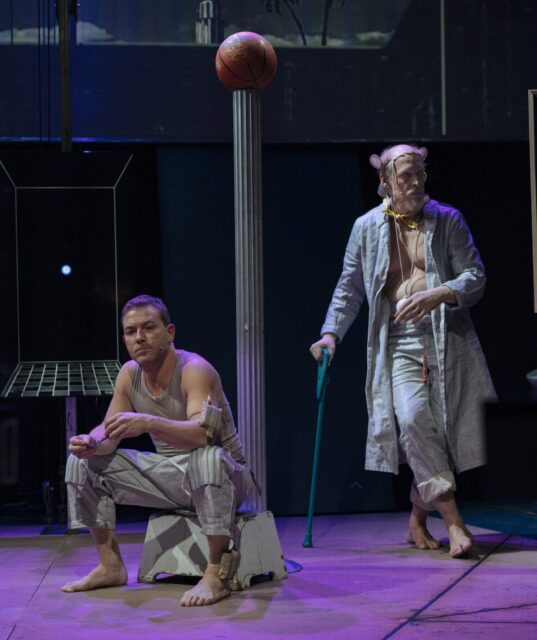

Naomi Lorrain and Toby Onwumere both play characters named Jordan in Ife Olujobi’s new play at the Public (photo by Joan Marcus)

JORDANS

LuEsther Hall, the Public Theater

425 Lafayette St. at Astor Pl.

Tuesday – Sunday through May 19, $65-$170

publictheater.org

“A reckoning is coming and the likes of you will be crushed by the likes of me!” the enslaved James tells his owner, Thomas Jefferson, in Sally & Tom, one of three current shows with ties to the Public Theater that deal with race and gender discrimination — and a coming reckoning.

At the Public’s LuEsther Hall, Ife Olujobi’s Jordans is set at a modern-day photo studio called Atlas, where some heavy lifting has to be done. The small company is run by the white, domineering Hailey (Kate Walsh), whose staff consists of the white Emma (Brontë England-Nelson), Fletcher (Brian Muller), Tyler (Matthew Russell), Ryan (Ryan Spahn), and Maggie (Meg Steedle) as well as a Black woman named Jordan (Naomi Lorrain), who they all treat, well, like an enslaved woman. While the others bandy about ridiculous ideas regarding Atlas’s future, Jordan has coffee purposefully spilled on her, is told to clean up vomit and human waste, gets garbage thrown at her, and is essentially ignored when she’s not being harassed.

When a photographer (Spahn) is snapping pictures during a photo shoot, he calls out to the model (England-Nelson), “Tell me, who is this woman? What does she want?” It’s a question no one asks Jordan.

Concerned that the company is becoming “vibeless” because their personnel lacks diversity, Hailey hires a Black man also named Jordan (Toby Onwumere) as their first director of culture. When 1.Jordan, as he’s referred to in the script, arrives for his first day, he asks Jordan, “What’s a brotha need to know?” And she tells him: “Well . . . the way I see it is, I work in an office owned by an evil succubus, staffed by little L-train demons, and I spend all day trying not to fall into their death traps. Sometimes it feels kinda like a video game: me running around, dodging flying objects, trying to save my lives for future battles. But then I remember this is my actual life, and I only have one. So.”

Hailey enters and runs her hands over 1.Jordan’s body as if she were evaluating a slave she has just purchased. Maggie demands to know where he is from — and she does not mean where he was born and raised, which happens to be in America. Fletcher, Emma, Tyler, and Ryan bombard him with questions about why his father was not around and was such a deadbeat. The stereotypes keep coming, but 1.Jordan stands firm, even as Hailey asserts to him when they are alone, “I am the owner of this studio.” He has been hired to be the (Black)face of the company and to do whatever he is told. Did I mention that 1.Jordan’s last name is Savage?

Outside the office, the two Jordans disagree on how to “play the game.” Jordan advises 1.Jordan to keep his head down, follow the rules, and not to show off his accomplishments. “You have to let them think that they own you,” she says. But 1.Jordan is determined to be a success on his terms, not theirs, arguing, “I want the freedom to do what I want without having to beg.”

Soon the Jordans become interchangeable, their roles and responsibilities merging and veering off in strange ways, each seeing the white world they inhabit from a new viewpoint. “Who are you?” Jordan asks. 1.Jordan replies, “Who am I?!” Meanwhile, the racist clichés ramp up even more.

Ife Olujobi’s Jordans is set at a modern-day branding studio (photo by Joan Marcus)

In her 2021 pandemic book No Play, in which Olujobi interviewed hundreds of theater people about the state of the industry as impacted by current events — I was among the participants — she asks in the chapter “the end of all things as we understand them”: “In the context of the racial and social justice movements reinvigorated by last year’s uprisings in response to the police killings of Black people, and in the simplest and most literal terms possible, what does ‘doing the work’ mean to you?”

Jordans — the title instantly makes one think of Michael Jordan’s heavily marketed and branded sneakers — is about doing the work, no matter your race or gender. Olujobi, in her first off-Broadway play, and director Whitney White (Jaja’s African Hair Braiding, On Sugarland) don’t back away from harsh language and brutal situations to make their points about where we have to go as a nation, when to take action, and when to sit back and listen. At a talkback after Donja R. Love’s Soft in 2022, White, who directed the show, told the audience that white people were not allowed to take part in the discussion. It was a sobering experience that has remained with me.

Lorrain (Daphne, La Race) and Onwumere (Macbeth, The Liar) are superb as the two Jordans, who get under each other’s skin both literally and figuratively. In an intimate and potent sex scene, only Lorrain’s vulva is exposed, not for titillation, but to declare that power and success do not require a penis. Walsh (If I Forget, Dusk Rings a Bell) excels as Hailey, who represents white leaders of all kinds.

The narrative has a series of confusing moments, and it’s too long at 140 minutes (with intermission); the scene with influencer Kyle Price (Russell) feels particularly extraneous, draining the story of its thrust. But the finale makes a powerful statement that won’t be easy to forget.

Sally Hemings (Sheria Irving) and Thomas Jefferson (Gabriel Ebert) pause at a dance in Suzan-Lori Parks’s new play at the Public (photo by Joan Marcus)

SALLY & TOM

Martinson Hall, the Public Theater

425 Lafayette St. at Astor Pl.

Tuesday – Sunday through June 2, $65-$170

publictheater.org

Pulitzer Prize winner Suzan-Lori Parks pulls no punches in her sharp and clever Sally & Tom, continuing at the Public’s Martinson Hall through June 2. It’s a meta-tale about different kinds of enslavement, from the start of America to the present day.

An independent, diverse theater troupe called Good Company is rehearsing its latest socially conscious play, The Pursuit of Happiness, the follow-up to Patriarchy on Parade and Listen Up, Whitey, Cause It’s All Your Fault. It’s set in Monticello, Virginia, in 1790, at the plantation home of Thomas Jefferson, who is in the midst of a sexual “relationship” with Sally Hemings, one of his slaves; he first started having sex with her when she was fourteen and he was forty-four. The show-within-the-show is written by Luce (Sheria Irving), a Black woman who plays Sally; her partner, the white Mike (Gabriel Ebert), is the director and portrays Tom. Dramaturg and choreographer Ginger (Kate Nowlin) is Patsy, one of Tom’s daughters; stage manager and dance captain Scout (Sun Mee Chomet) is Polly, Tom’s other daughter; publicist and fight director Maggie (Kristolyn Lloyd) is Mary, Sally’s sister; music, sound, and lighting designer Devon (Leland Fowler) is Nathan, Mary’s husband; Kwame (Alano Miller), who is looking to break out into film, is James, Sally’s older brother; and set and costume designer Geoff (Daniel Petzold) plays multiple small roles.

The opening scene between Sally and Tom sets the stage.

Tom: Miss Hemings?

Sally: Mr. Jefferson?

Tom: What do you see?

Sally: I see the future, Mr. Jefferson.

Tom: And it’s a fine future, is it not?

Sally: God willing, Mr. Jefferson.

Tom: Do you think we will make it?

Sally: Meaning you and I?

Tom: Meaning you and I, of course, and, meaning our entire Nation as well. Do you think we’ll make it?

Sally: God willing, Mr. Jefferson. God and Man willing. And Woman too.

While Tom is keeping his relationship with Sally secret, Mike and Luce do not hide theirs, although Luce is suspicious of Mike’s ex. Art imitates life as what happens in the play is mimicked by what is occurring to the company members. When Luce points out, “This is not a love story,” she might be talking about not only Sally and Tom but her and Mike. When unseen producer Teddy demands that a key speech by Kwame, aka K-Dubb, be cut and threatens to pull his funding, the company has some important decisions to make that evoke choices that Sally and Tom are facing. Jefferson admits to owning six hundred enslaved people, including Sally and her family, while Luce declares, “Teddy don’t own me.” And just as the company was depending on the money promised by Teddy, Sally and James are quick to prod Tom of his vow to eventually free them. “We build our castle on a foundation of your promises,” Sally tells Tom.

“Handing me a book while you keep me on a leash,” James says to Tom. “Do you want me to remind myself of how kind you are? Kinder than other Masters, hoping that I will rejoice every day that you keep me enslaved? Let me proclaim my Liberty: You are not on the Throne! I stand with all Enslaved People who rise up and revolt! I say ‘Yes’ to the Revolutions that explode and that will continue to explode all over this country. I condemn the ‘breeding farms’ not more than a day’s ride from here. I acknowledge all the Horrors and the Revolutions that you dare not think on, and that we dare not speak of in your presence. What would we do if we were to wake up out of our ‘tranquility’? The wrongs done upon us would be avenged. And the world order would be upended!”

As Tom decides whether he should go to New York City at the behest of the president and who he will bring with him, Luce and Mike have to reconsider the future of the play, and their partnership.

Sally & Tom is about a small theater company putting on historical drama (photo by Joan Marcus)

Presented in association with the Guthrie Theater, Sally & Tom might not be top-shelf Parks — that illustrious group includes Topdog/Underdog, Father Comes Home from the Wars (Parts 1, 2 & 3), In the Blood and Fucking A, and Porgy and Bess — but it’s yet another splendidly conceived work from one of America’s finest playwrights. Parks and director Steve H. Broadnax III (Sunset Baby, The Hot Wing King) breathe new life into a familiar topic, which has previously been explored in film and opera as well as television, music, and literature.

Irving (Romeo and Juliet, Parks’s White Noise) and Tony winner Ebert (Matilda, Pass Over) are terrific as the real couple from the past and the fictional contemporary characters, their lives becoming practically interchangeable on Riccardo Hernández’s set, which contains Monticello-style pillars, the actors dressed in Rodrigo Muñoz’s period costumes. The score was written by Parks with Dan Moses Schreier; Parks, an accomplished musician, composed and played the songs for her intimate 2022–23 Plays for the Plague Year, and on April 29 she appeared at Joe’s Pub with her band, Sula & the Joyful Noise.

“You will be ashamed that you were proud to father a country where some are free and others are enslaved! Where some have plenty and others only have the dream of plenty!” Kwame proclaims to Tom. “All them pretty words you write, Mr. Jefferson, they’re all lies! You’ll soon be ashamed by the lies that this country was built on, Mr. Jefferson! Ashamed by the lies on which we were founded, and on which we were fed, and on which we grew fat!”

As Jordans and Sally & Tom reveal, those lies are still with us, more than two hundred and thirty years later.

Shaina Taub wrote the book, music, and lyrics and stars in Suffs on Broadway (photo by Joan Marcus)

SUFFS

Music Box Theatre

239 West 45th St. between Broadway & Eighth Aves.

Wednesday – Sunday through January 5, $69 – $279

suffsmusical.com

The reckoning forges ahead at Suffs, Shaina Taub’s hit musical that began at the Public’s Newman Theater in 2022 and has now transferred to the Music Box on Broadway in a rearranged and improved version.

Most Americans are familiar with such names as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, but Taub focuses on the next generation of women who fought for the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in the second decade of the twentieth century: Alice Paul (Taub), Inez Milholland (Hannah Cruz), Doris Stevens (Nadia Dandashi), Lucy Burns (Ally Bonino), and Ruza Wenclawska (Kim Blanck).

The musical focuses on generational conflict and disagreements about strategy that have characterized all sorts of progressive movements in the United States; an older, more sedate crowd wants to work within the system, while young radicals want to bust it open with outright aggression.

In Suffs, the youngsters decide to take on the powerful National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), led by Carrie Chapman Catt (Jenn Colella) and Mollie Hay (Jaygee Macapugay), a group that does not want to ruffle any feathers. While Carrie sings, “Let mother vote / We raised you after all / Won’t you thank the lady you have loved since you were small? / We reared you, cheered you, helped you when you fell / With your blessing, we could help America as well,” Alice declares, “I don’t want to have to compromise / I don’t want to have to beg for crumbs / from a country that doesn’t care what I say / I don’t want to follow in old footsteps / I don’t want to be a meek little pawn in the games they play / I want to march in the street / I want to hold up a sign / with millions of women with passion like mine / I want to shout it out loud / in the wide open light.”

While Carrie is content to set up pleasant meetings with President Woodrow Wilson (Grace McLean) that are either nonproductive or canceled, Alice has no patience, demanding that action happen immediately. After seeing Ruza give a rousing speech at a workers rally, Alice asks her to join their movement. “Look, I want no part of your polite little suffragette parlor games,” Ruza says. Alice responds, “Well, that’s perfect, because when we take on a tyrant, we burn him down.”

One of the most troubling aspect of the fight for twentieth-century women’s suffrage is its relationship with Black-led racial justice and civil rights movements. Suffs does not ignore the issue and instead makes it a major plot point. When Black journalist and activist Ida B. Wells’s (Nikki M. James) offers to bring her group to join the march, Alice initially rejects her, fearing that southern white donors will pull their funding, but Ida won’t take no for an answer.

“I’m not only here for the march,” Ida tells Alice and the others. “My club has also come to agitate for laws against lynching; my people cannot vote if they are hanging from trees.” She also proclaims in the showstopper “Wait My Turn”: “You want me to wait my turn? / To simply put my sex before my race / Oh! Why don’t I leave my skin at home and powder up my face? / Guess who always waits her turn? / Who always ends up in the back? / Us lucky ones born both female and black.”

Despite the march’s surprising success, the suffragists still have their work cut out for them if they are going to convince the powers that be that women deserve the right to vote.

Inez Milholland (Hannah Cruz) leads the charge for women’s right to vote in Suffs (photo by Joan Marcus)

Taub’s (Twelfth Night, As You Like It) lively score, with wonderful orchestrations by Michael Starobin, and sharp lyrics keep the show moving at a fast pace, matching Alice’s determination to break down political malaise by getting things done ASAP. Tony nominee Leigh Silverman (Merry Me, Grand Horizons) directs with a stately hand that never lets the energy slow down.

Taub fully embodies Alice, a fierce, driven fighter you would want on your side no matter the issue. Tony nominee Colella (Come from Away, Urban Cowboy) is a terrific foil as Carrie; their battles are reminiscent of those between Gloria Steinem and Phyllis Schlafly over the ERA in the 1970s — which Alice also was a part of. Tony winner James (The Book of Mormon, A Bright Room Called Day) brings down the house with “Wait My Turn,” and, in their Broadway debuts, Bonino is lovable as Lucy, Blanck (Octet, Alice by Heart) is a force as Ruza, Cruz rides high as Inez, Dandashi is sweet as the nerdy Doris, and Tsilala Brock adds a sly touch as Dudley Malone, President Wilson’s chief of staff.

As in Jordans and Sally & Tom, Taub’s Suffs explores various aspects of race- and gender-based discrimination, and each offers a very different conclusion.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]