Nina (Moses Ingram) and her father, Kenyatta (Russell Hornsby), meet for the first time in years in Sunset Baby (photo by Marc J. Franklin)

SUNSET BABY

The Pershing Square Signature Center

The Romulus Linney Courtyard Theatre

480 West 42nd St. between Tenth & Eleventh Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through March 10, $49-$119

212-244-7529

signaturetheatre.org

“History is bullshit. Only thing matters is the present. The past don’t do a damn thing but keep you chokin’ on bad memories,” Damon (J. Alphonse Nicholson) says in Steve H. Broadnax III’s blistering revival of Dominique Morisseau’s Sunset Baby at the Signature.

Family legacy is at the heart of the play, which debuted in 2013 from the LAByrinth Theater Company. It’s the early 2000s in East New York, where Nina (Moses Ingram), teaming up with Damon, dresses up like a street hooker to sell drugs and steal from people. Nina’s mother, 1960s radical civil rights activist Ashanti X, has died, leaving behind a stack of love letters she wrote but never sent to Nina’s father, Kenyatta Shakur (Russell Hornsby), while he was in prison. Academics, publishing companies, and the press are after the letters and are willing to pay good money for them, but then Kenyatta shows up at his daughter’s doorstep, claiming he just wants to read them.

Nina, who was named after singer, composer, and activist Nina Simone, doesn’t trust this man, whom she considers a stranger; they haven’t seen each other in decades since he left. But Damon, always on the lookout for a deal, is interested in hearing what Kenyatta has to offer.

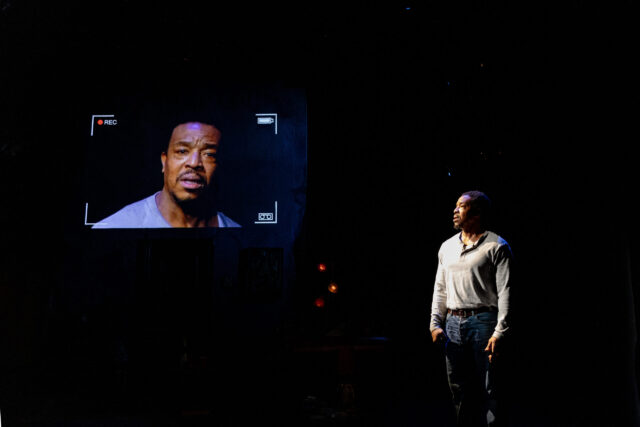

Several times during the play, Kenyatta stands alone, making a camcorder video that is projected on three screens. (The stark projections are by Katherine Freer.) In the first one, he essentially introduces the topics that the story will touch on. He says, “Fatherhood. Complex. Complicated. An abstract concept. Not clearly definable. Stages. For sure there are stages. Levels of its affectiveness. Affectionless. Manhood. Confusion. Preparedness. Lack of preparation. Funding. Resources. Instructions. No instructions. Child support. Life being run by child support. Drama. Suffocation. Lots of suffocation. Guilt. Lots of guilt. Incompetency. Freedom. Freedom lost. Freedom never acquired. Fear. Lots of fear. Decades and decades of fear. Lifetime of fear. Lifetime of fear. Fear. Fear.”

Damon praises Kenyatta’s activist past and sees the two of them as somewhat similar, telling him, “The fuck-the-government, disrupt capitalism, develop-our-own-economy type shit. I’m with it. Believe in that cause myself. My line of work is a little different, but same principles.”

Damon has a son of his own with another woman; the relationship is one of potential abandonment, echoing Kenyatta’s abandonment of Nina. “When a man wants to spend time with his child, shouldn’t be not a goddamn thing that gets in his way,” she tells Damon. She dreams of saving enough money to leave New York City for Europe, and Damon seems ready to go anywhere with her, thinking they are an inseparable Bonnie and Clyde. But nothing for Nina has ever been easy.

Nina (Moses Ingram) and Damon (J. Alphonse Nicholson) make plans for a better life in Signature revival (photo by Marc J. Franklin)

Sunset Baby recalls Suzan-Lori Parks’s 2001 Pulitzer Prize–winning Topdog/Underdog, in which two brothers contemplate their fate in their cramped, tiny apartment in a rooming house, one a petty thief, the other a bluesman portraying Abraham Lincoln at an arcade, both holding on to a small inheritance their mother left them. Nina lives in a tiny, cluttered studio apartment with decaying walls and the bathroom down the hall; however, where Arnulfo Maldonado’s set for the recent Broadway revival of Topdog/Underdog was claustrophobic, penning the characters in like a kind of prison, Wilson Chin’s set for Sunset Baby is more open, suggesting that Nina may be able to escape and seize the freedom she so desires. Emilio Sosa’s costumes delineate Nina from the two men in her life; Kenyatta and Damon wear ordinary, everyday jeans, shirts, and jackets, while Nina puts on glittery and shiny red and blue tight-fitting outfits, fancy boots, and any of a number of long wigs, only occasionally relaxing on her couch without all the glitz of the street.

Songs by Simone, who died in 2003 at the age of seventy, are scattered throughout the show, including “Love Me or Leave Me” (“My baby don’t care for shows / My baby don’t care for clothes / My baby just cares for me”), “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood” (“I’m just a soul whose intentions are good / Oh, Lord, please, don’t let me be misunderstood”), and “Feeling Good” (“Stars when you shine, you know how I feel / Scent of the pine, you know how I feel / Oh, freedom is mine / And I know how I feel”), the tunes moving from the background to the foreground, lifting through the theater, courtesy of co–sound designers Curtis Craig and Jimmy “J. Keys” Keys.

Kenyatta (Russell Hornsby) tries to explain himself in a series of videos in Dominique Morisseau revival (photo by Marc J. Franklin)

Broadnax III (Thoughts of a Colored Man, The Hot Wing King) lets Morisseau’s (Skeleton Crew, Confederates) rhythmic, potent dialogue sing; words flow out of Nicholson (Paradise Blue, A Soldier’s Play) like music. Hornsby (King Hedley II, Fences) is convincing as the complicated Kenyatta, who always seems to be holding something back. And Emmy nominee Ingram (The Queen’s Gambit, The Tragedy of Macbeth), in her off-Broadway debut, is a powerhouse as Nina, a woman desperate to break free of the legacy that weighs her down.

In a program note, the Detroit-born Morisseau writes that when Sunset Baby debuted at the LAByrinth, it was only her second professionally produced play in New York City, her father was still alive, and she was “not yet a mother. Only a daughter.” But this revival has given her new insight into herself and activist movements, “that they are complex and most people can only understand the trauma from the side they are on, never from the assumed opposition.” She also points out, “My father believed in revolution so much that he espoused it on a daily. Our answering machine message would end with ‘long live the revolution.’ It took many years for me to understand what that meant to him. And then what it meant to me.”

That explanation lends underlying meaning to the relationship between parents and children when Nina declares to Damon, “I don’t need to be part of a revolution. I don’t want a movement or a cause. I don’t want a hustle or no fast money. I want a home. I want somewhere I can walk into my space and not have to look over my shoulder or hold my breath. I want some kids of my own. . . . I wanna sit in the horizon somewhere and watch the sun rise and set. I never even saw a fuckin’ sunset! I am not alive here. I am not alive in this chaos — you hear me? I do not want this shit no more.”

Nina just wants to be understood in a world that insists on defining her, but in Sunset Baby, Morisseau gives her voice and has it rise to the rafters and beyond.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]