Pastor Freeman says goodbye to Brother Righttocomplain’ in Jordan E. Cooper’s Ain’t No Mo’ (photo by Joan Marcus)

AIN’T NO MO’

The Public Theater, LuEsther Hall

425 Lafayette St. by Astor Pl.

Tuesday – Sunday through May 5

212-967-7555

www.publictheater.org

The Public Theater is currently presenting two very different new plays that tackle America’s shameful legacy of slavery and systemic racism head-on, incorporating uncomfortable humor into angry works that pull no punches. Actor and playwright Jordan E. Cooper’s Ain’t No Mo’ consists of a series of hit-or-miss comic vignettes — mostly the former — built around the premise that the United States of America is sending all the black people in the country back to Africa on free flights. The stairway leading up to LuEsther Hall is lined with stenciled signs that announce, “Welcome to African-American Airlines . . . where if you broke & black we got yo back! . . . Fasten your seatbelts, it’s going to be a fast & furious ride.” It is indeed a fast and furious ride, performed by the talented cast of Marchánt Davis, Fedna Jacquet, Crystal Lucas-Perry, Ebony Marshall-Oliver, Simone Recasner, Hermon Whaley Jr., and Cooper like they are on a live variety show.

“Real Baby Mamas of the South Side” is one of several wild vignettes in play at the Public Theater (photo by Joan Marcus)

The first scene takes place on November 4, 2008, the night that Barack Obama was elected the first black president of the nation. Pastor Freeman is delivering a fiery eulogy for the dear departed Brother Righttocomplain’, declaring that with a black man in the White House, black people can no longer criticize and blame society for any woes they experience. “Because the president is a n-gga there ain’t no mo’ discrimination, ain’t no mo’ holleration, ain’t gone be NO more haterration in this dancerie, do you hear me what I say? I say it ain’t no mo’,” he preaches to his devoted flock. He demands that the audience shout out, “The president is my n-gga,” but none of the white people in the theater take him up on it. In the next scene, “reparations flight” stewardess Peaches (played in fab drag by Cooper) explains on the phone, “Well, bitch, I don’t know what to tell you ’cause if you stay here, you only got two choices for guaranteed housing and that’s either a cell or a coffin. After this flight, there will be no more black folk left in this country, and I know ya’ll don’t wanna be the only ones left behind because them muthafuckas will try to put you in a museum or make you do watermelon shows at SeaWorld and shit. Hurry up or I will give your seat to some of the Latinos on stand-by.”

Peaches (playwright Jordan E. Cooper) helps all the African Americans leave the country in Ain’t No Mo’ (photo by Joan Marcus)

Other scenes in the two-hour intermissionless play are set in an abortion clinic where millions of black women are terrified of bringing a son into this dangerous racist world, a television reality show in which a white woman is transitioning into becoming black, and a mansion where a wealthy black family is keeping a black slave in the basement, hiding not only him but also their own identities. Kudos are due Kimie Nishikawa’s goofy, imaginative sets, Montana Levi Blanco’s flashy costumes, and Cookie Jordan’s hysterical hair, wig, and makeup design. Cooper gets right to the point when a woman at the clinic tells a reporter, “The problem is we’re racing against a people who have never had to compete, and people who have never had to compete are fearful of competition and they will annihilate any being that challenges their birth-given promise of a victory.” As wildly funny, if occasionally over the top and too scattershot, as Ain’t No Mo’ can be, it’s also a bitter pill to swallow. At the end of the show, a large American flag unfurls from above and the cast stands in front of it, arms folded, staring accusingly at the audience; there are no smiles or bows, but there is raucous applause from the seats.

Dawn (Zoë Winters) tries to help Leo (Daveed Diggs) through a traumatic event in Suzan-Lori Parks’s White Noise (photo by Joan Marcus)

WHITE NOISE

The Public Theater, Anspacher Theater

425 Lafayette St. by Astor Pl.

Tuesday – Sunday through May 5

212-967-7555

www.publictheater.org

Suzan-Lori Parks’s White Noise explores many of the same themes as Ain’t No Mo’, but the Pulitzer Prize winner does so in a far more controlled environment, a compelling and surprising work that will hit you in the gut even as it makes you laugh. Directed by Public Theater head Oskar Eustis, White Noise begins with a long monologue beautifully delivered by Daveed Diggs as Leo, sitting in a red chair, discussing his inability to sleep, which began at the age of five when a woman in a church basement told him, “Leo, I know you know how the sun shines up above. But do you also know that, one day, the sun is going to die? You know that, don’t you? One day the sun is going to die, and everything in the whole world is gonna go all black.” He explains that he is going to tell us about “me and Dawn and Misha and Ralph” (a sly reference to Christopher Durang’s Chekhov takeoff Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike as well as Paul Mazursky’s 1969 romantic comedy Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice?), four friends who went to college together and now, in their thirties, are trying to settle down and figure out what to do with their lives.

Four college friends go bowling in world premiere at the Public (photo by Joan Marcus)

Leo is a self-described “fractured and angry and edgy black visual artist” who has been unable to create and has recently been brutalized by the police while out on a walk because of his insomnia. “I thought they were going to shoot me. I thought, I’m going to be one of those guys that they shoot,” he says. He is living with Dawn (Zoë Winters), a white social justice lawyer on an important, sensitive case involving a teenager. Leo used to be with Misha (Sheria Irving), a black woman who hosts an internet call-in show titled Ask a Black and is now living with Ralph (Thomas Sadoski), Dawn’s previous lover, a white teacher from a wealthy family who is up for a prestigious tenured position at his college. The four talk about life, love, careers, their brief band, and more while bowling, a sport the men lettered in at school. But Leo shocks them when he announces he has an outrageous, completely controversial forty-day plan to protect himself from the racist powers that be. “Should They stop me next time, I will have something to say. Something that would give Them pause. Make Them think. Make Them leave me be. Make Them leave me the fuck alone,” he tells his friends, who think he is nuts, and even more so when Ralph agrees to take part in it. “Like the brother said, ‘Nothing can be changed until it’s faced,’” Leo says, quoting James Baldwin. “The pain and rage need to get worked out of my system. I’ll take myself to the lowest place and know for ever after that if I can bear it, then I can bear anything. And my mind will be free.”

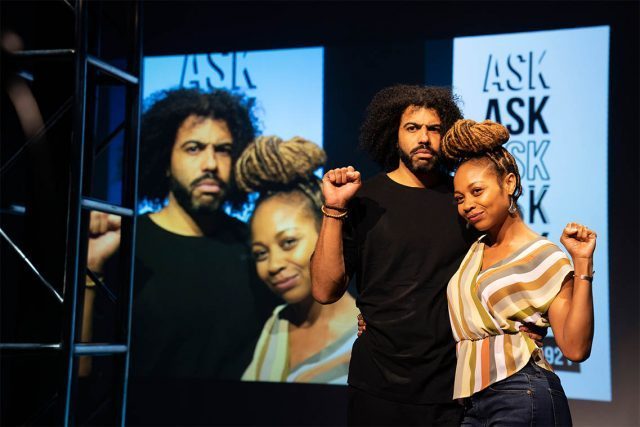

Leo (Daveed Diggs) and Misha (Sheria Irving) fight the power in White Noise (photo by Joan Marcus)

White Noise is superbly presented by Eustis (Julius Caesar, Compulsion), who directs with a sharp understanding of the complex material. Clint Ramos’s set is centered by a bowling lane where the characters roll their balls that disappear under the audience and then return to the back of the stage. Is it too simplistic to suggest that balls of multiple colors knocking down white pins is a metaphor? It’s also dramatic and entertaining, the sound of the ball hitting the lane and rolling out of sight echoing through the theater. (The cool sound design is by Dan Moses Schreier.) Diggs (Hamilton, Blindspotting), Winters (An Octoroon, Love and Information), Sadoski (Other Desert Cities, reasons to be pretty), and Irving (Crowndation, While I Yet Live) are a bright, youthful ensemble who skillfully navigate plot twists that shake their characters’ foundations. Parks’s (Topdog/Underdog, Fucking A) potent dialogue, well-drawn characters, and daring situations make the play’s three hours and fifteen minutes pass gracefully. Some of the scene changes are accompanied by music from Parks’s band, which has played at the Public and other venues. (In addition, Parks, the institution’s first Master Writer Chair, is performing the free Watch Me Work in the lobby mezzanine on select Mondays at 5:00, a “play with an action and dialogue” that is “also a meta-theatrical free writing class.”) White Noise and Ain’t No Mo’ are a bold one-two punch, the former from a playwright at the top of her craft, the latter from a fearless up-and-comer filled with promise.