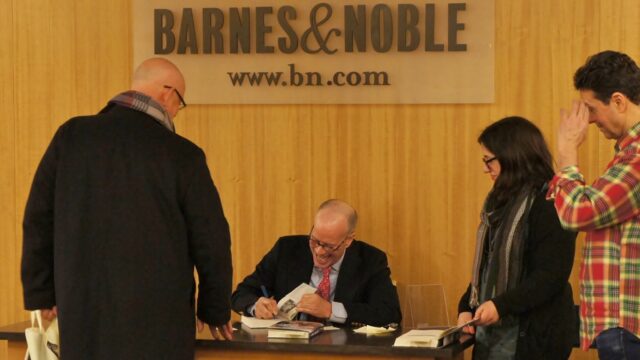

Andrew Scott reaches for dying hope in Vanya at the Lucille Lortel (photo by Julieta Cervantes)

VANYA

Lucille Lortel Theatre

121 Christopher St. between Bleecker & Hudson Sts.

Tuesday – Sunday through May 11

lortel.org/currently-playing

There are currently two extraordinary solo shows, one on Broadway, one off, based on classic literary works from the 1890s, and they could not be more different.

Both feature extremely talented and sexy award-winning actors from English-speaking countries overseas; in one, the performer creates a warm, intimate space, attempting to make individual eye contact with each of the 299 audience members, while in the other the star spends nearly the entire show looking directly into onstage cameras, although every one of the 1,025 audience members will feel the power and intelligence in that gaze.

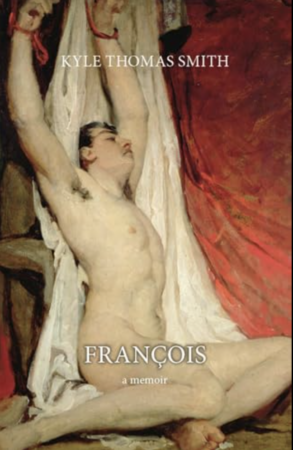

At the Lucille Lortel in the West Village, Dublin-born Andrew Scott, a three-time Emmy nominee and two-time Olivier winner who has portrayed Moriarty in Sherlock, the hot priest in Fleabag, the title character in Ripley, and Adam in Andrew Haigh’s well-received 2023 film, All of Us Strangers, is taking on all eight roles in Simon Stephens’s adaptation of Anton Chekhov’s 1899 Uncle Vanya, called simply Vanya.

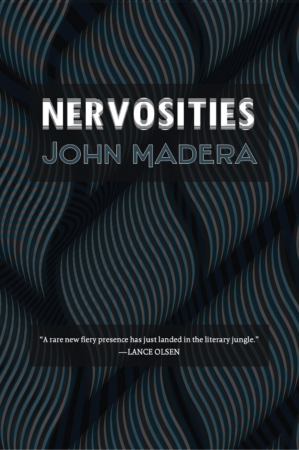

Meanwhile, Adelaide-born Sarah Snook, an Emmy and Olivier winner who is most well known as Siobhan “Shiv” Roy in Succession, plays all twenty-six parts in Kip Williams’s adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s 1890 novella, The Picture of Dorian Gray.

Under the whimsical direction of Sam Yates — who created the show with Scott, writer Stephens, and scenic designer Rosanna Vize — Scott, whose only previous New York stage appearance was in David Hare’s The Vertical Hour in 2006–7, employs only subtle shifts in his performance to indicate which character he is at any given moment, with slight vocal changes and the use of such objects as a tennis ball, sunglasses, a necklace, and a scarf. Vize’s attractive set includes a kitchen with a working sink, a door standing by itself in the center, a piano with a small Christmas tree on it, a glowing orb, a table with a lamp and bottle of booze, a large swing, and a curtained back wall that opens to reveal a mirror in which the audience can glimpse themselves, a way to combat the solitude of the solo performer and involve the audience even further.

It definitely helps to know the basics; as one colleague noted to me after the show, “I enjoyed it, but was it Uncle Vanya?” Over the years, the play has proved to be malleable, reshaped and reimagined into various time periods and locations and methods of storytelling. Tony winner Stephens, who has written such diverse presentations as The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, Heisenberg, and Blindness, sets his version in an undefined time and place, although it seems to be the latter part of the twentieth century, before cell phones and home computers; he has Anglicized the names, added nearly three dozen F-bombs, and references the 1994 Johnny Depp movie Don Juan de Marco.

Ivan (Ivan Petrovich “Vanya” Voynitsky) and his niece, Sonia (Sofya Alexandrovna), run the family estate owned by Alexander (Aleksandr Vladimirovich Serebryakov), Sonia’s father; a pompous film director, he was married to Anna, Ivan’s late sister and Sonia’s mother. Alexander has arrived with his much younger second wife, Helena (Yelena Andreevna), who is lusted after by Ivan and the local country doctor and environmentalist, Michael (Mikhail Lvovich Astrov). Ivan’s cranky, well-read, aging mother, Elizabeth (Maria Vasilevna Voynitskaya), lives at the estate, along with the old nurse Maureen (Marina Timofeevna) and Liam (Ilya Ilich “Waffles” Telegin), a poor landowner and family friend who has not gotten over his wife’s desertion with another man years before, opting to remain faithful to her until her utterly unlikely return.

Andrew Scott takes a swing and scores as eight characters in solo Uncle Vanya (photo by Julieta Cervantes)

The play opens with a conversation between Michael and Maureen that relates to all the characters:

Michael: How long have we known each other, Maureen?

Maureen: Oh my god, Jesus. Let me think. You came here for the first time, when was it, when Anna, Sonia’s mother, was sick? Then you had to come again the next year. That was two visits in two summers before . . . before she died. So that’s eleven years, is it?

Michael: Have I changed, do you think?

Maureen: Oh god yeah. You have. You used to be so handsome. And you were so young then, Michael, and now you’re old. And of course you drink more than you used to, Michael.

Michael: Yeah . . . Yeah I’ve worked myself to the bone. I’m on my feet all day. I never rest. And then you get home and you pray to God a patient isn’t going to call you out again. But they do, they always do. So in all the time I’ve known you, Maureen. In the last decade. I’ve not had a single day off. What do you expect me to do but get old? And then you look around you and all you can see are lunatics. The people here are lunatics, Maureen. Every single one of them. And when you surround

yourself with lunatics, after a while, you become a lunatic too. I’ve started growing my own carrots. Little tiny carrots. How did that happen? See, I’ve become a lunatic too. It’s not that I’m losing my mind. My brain is still largely in the right place. But my feelings are dull and dead. I don’t want anything. I don’t need anything. I don’t love anybody. Except you. I love you, Maureen.

Maureen: Are you sure you don’t want a drink?

Shortly after that, Ivan, who deeply resents Alexander, explains to Michael and Maureen that he hasn’t been sleeping well, “ever since Alexander and his new wife got here. They’ve knocked our lives completely out of kilter. I sleep really deeply at absolutely the wrong times of day. I’m eating all this weird food. From, like, Kabul. I’m drinking wine in the day. It’s not good for me, Doctor. It’s not good for me at all. Before they got here I didn’t have a moment to spare, did I, Maureen? I was working all the time. Me and Sonia were. Preparing the harvest. Managing the orders. Making deliveries. Now it’s just Sonia that’s doing everything, because all I do is eat, sleep, drink, repeat, eat, sleep, drink, repeat!”

But when Alexander reveals his plans for the estate and Ivan catches Michael with Helena, one of the most famous guns in the history of theater explodes.

Vanya is a unique and thrilling experience. Scott is absolutely magnetic; you won’t be able to take your eyes off him, just as it feels like he can’t take his eyes off you. There are odd moments; turning Alexander into a film director feels unnecessary, and a sex scene is both steamy and awkward, given that Scott is playing both roles.

But overall, the hundred-minute show is as wistful and funny as it is heart-wrenching and touching. The incorporation of the piano to recall Anna is haunting, and the swing evokes a more innocent childhood for Ivan, Scott, and the audience.

Early on, Elizabeth tells Ivan, “You’ve changed, Ivan. Sorry, Sonia, but it’s true. You’ve become cynical. I barely recognize you these days. You had a good soul. You used to be so clear in your convictions. They used to shine from you. . . . What’s odd, Ivan, is that it’s like you blame your misery on your convictions. Your convictions aren’t the problem. You’re the problem. You never put your convictions into practice. You could have gone out and done something. You never did.” Vanya responds, “Done something? Do you have any idea, Mother, how difficult it is to go out and ‘do something’ nowadays?” That’s an exchange everyone can relate to in 2025.

So is it Uncle Vanya?

In Andrew Scott’s capable hands, does it matter?

Sarah Snook portrays all the characters in unique staging of Oscar Wilde classic (photo by Marc Brenner)

THE PICTURE OF DORIAN GRAY

Music Box Theatre

239 West 45th St. between Broadway & Eighth Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through June 29, $74–$521

doriangrayplay.com

Sarah Snook is sensational in her New York stage debut, portraying all the characters in Kip Williams’s exciting solo adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s beloved homoerotic gothic horror morality tale, The Picture of Dorian Gray. For two hours without intermission, Snook, who won an Olivier for her performance in London, ambles across the stage, followed by several mobile cameras operated by Clew, Luka Kain, Natalie Rich, Benjamin Sheen, and Dara Woo, dressed in black, stopping behind and in front of several large screens hanging from the ceiling. A giant Snook is projected onto the screens, dominating the theater as she smiles, winks, and nods knowingly while the dark story unfolds.

The genius in the Sydney Theatre Company production is that the onstage Snook interacts with prerecorded versions of herself as the other characters; thus, the live Snook is seen having conversations with the others on the screens, sometimes several at a time, all aware that they are being looked at and reveling in that connection.

Artist Basil Hallward has painted a portrait of a beautiful young man named Dorian Gray. Showing the work to his aristocratic friend Lord Henry “Harry” Wotton, who wants it to be shown publicly at a prestigious event, Hallward declines, explaining, “I know you will laugh at me, but I really can’t exhibit it. I have put too much of myself into it. . . . Harry, every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter. The reason I will not exhibit this picture is that I am afraid that I have shown in it the secret of my own soul.”

Dorian arrives at the studio to continue to pose for Basil, who does not want Lord Wotton to corrupt his innocent young model and new friend. He tells Harry to stay away from him, offering, “He has a very bad influence over all his friends, with the single exception of myself.” Dorian asks, “Have you really a very bad influence, Lord Henry? As bad as Basil says?” Lord Wotton replies, “There is no such thing as a good influence, Mr. Gray. All influence is immoral.” Saying he is glad to have met Lord Wotton, Dorian admits, “I wonder shall I always be glad?”

Upon seeing the finished portrait, Dorian is blissful yet taken aback. “How sad it is! How sad it is! I shall grow old, and horrible, and dreadful. But this picture will remain always young. It will never be older than this particular day of June,” he declares. “If it were only the other way! If it were I who was to be always young, and the picture that was to grow old! For that — for that — I would give everything! Yes, there is nothing in the whole world I would not give! I would give my soul for that!”

And thus, the deal is done.

Sarah Snook briefly takes a seat in The Picture of Dorian Gray (photo by Marc Brenner)

Dorian is taken under the wing of Lord Wotton’s aunt, Lady Agatha, and meets such high-society types as the Duchess of Harley, parliamentarian Sir Thomas Burdon, the charming gentleman Mr. Erskine of Treadley, and the silent Mrs. Vandeleur, an old friend of Lady Agatha’s who decided she had “said everything that she had to say before she was thirty.” Among the others who enter Dorian’s kaleidoscopic world are his housekeeper, Mrs. Leaf; actress and puppeteer Sibyl Vane; Francis Osborne, the doorman; chemist Alan Campbell; Dorian’s friend Adrian Singleton; and Sybil’s younger brother, sailor James Vane.

Murder, suicide, and other forms of mayhem ensue as Dorian’s bloom of youth and beauty never seem to fade despite his depravities while the portrait depicts an ever older and more decrepit figure.

Marg Horwell’s set is mostly spare except for a few props that appear briefly, such as a long table, a puppet show, and an elegant couch with flowers; Horwell’s period costumes and the many wigs Snook wears are fanciful and ornate. The pinpoint precision of Nick Schlieper’s lighting, Clemence Williams’s sound and music, and David Bergman’s video makes it all feel real, especially one scene in which a group is seated at a long table; it is not immediately clear which Snook is the live one. Williams and Bergman also have fun using face filters as Snook cheekily poses for the camera.

The only time Snook is not looking directly into the camera is when she is in the nursery, admiring herself in a handheld mirror; in one corner is a collection of portraits based on paintings by such artists as Sebastiano del Piombo, Jean-Étienne Liotard, and Bronzino, but each now with Snook’s face.

Snook is remarkable as the narrator and all the characters, able to engage with an audience she never actually looks at, acting to be seen on a screen as if the audience is watching a morphing portrait. Despite our being well aware of the artificiality of it all, we fall for the gambit hook, line, and sinker, sucked into this technological marvel; it is a Dorian Gray made for 2025.

It is also an excellent companion piece to Andrew Scott’s Vanya. Just as multiple characters in Stephens’s Chekhov retelling discuss how much others have changed, that concept is key to Dorian Gray as well, and not just in how the man in the portrait deteriorates but Dorian does not. “It’s nigh on eighteen years since I met him. He hasn’t changed much since then. I have, though,” Violet acknowledges. “You are quite perfect, Dorian. Pray, don’t change,” Lord Wotton insists. And Dorian asks of himself, “Was it really true that one could never change?”

In addition, an elusive happiness hovers over Vanya. “I may not have my happiness, Ivan. But I’ve got my pride,” Liam says. Michael debates whether he is happy or not. Sonia asks Helena if she is happy and she answers no. And Alexander brags, “I’m the only happy one in this whole bloody house.” Meanwhile, Lord Wotton says, “Pleasure is Nature’s test, her sign of approval. When we are happy, we are always good, but when we are good, we are not always happy.” And Dorian admits, “I have never searched for happiness. Who wants happiness? I have searched for pleasure.”

In completely different ways, both shows offer pleasures galore, delivering a happiness that will stay with you long after you leave the theater.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]