Matthew Barney, “Khu: Djed,” brush and ink, gold leaf, iron, and lapis lazuli on black paper in polyethylene frame, 2011 (copyright Matthew Barney / courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels)

Morgan Library & Museum

225 Madison Ave. at 36th St.

Daily through September 8, $12-$18 (free Fridays from 7:00 to 9:00)

212-685-0008

www.themorgan.org

www.drawingrestraint.net

No, the banner outside the Morgan Library proclaiming that its Matthew Barney exhibition ends September 2 is not a restraint to stop drawing visitors to the show, which actually closes September 8. For the first-ever museum retrospective of his drawings, the California-born multidisciplinary artist chose two very specific venues, both of which had to be libraries: the Morgan first, followed by the Bibliothèque nationale de France. For “Subliming Vessel: The Drawings of Matthew Barney,” the Park Slope-based former college quarterback and premed student combines pieces from the institutions’ holdings with his own works and research paraphernalia to lend new insight into his creative process and influences. Since the late 1980s, Barney has been making drawings that relate to his films, installations, and live performance events, the works serving not only as rehearsals or storyboards but also acting as part of the central focus of the narrative as well as continuing into the aftermath. “I would describe a system that I’ve always visualized as an inverted pyramid, where the narrative is at the widest point, at the top of the structure,” Barney tells artist Isabelle Dervaux in an interview in the exhibition catalog. “The narrative in most projects is film-based, video-based, in some projects performance-based, but it’s the most developed aspect of the project. From there a process of distillation happens. Sculpture comes next in the sense that sculpture often tries to articulate a relationship in the narrative between characters or between places. Drawing is at the bottom of this structure and is the most distilled aspect of it. In that way it’s one of the more rewarding — possible the most rewarding part of the process, to get down to the purest form, the most distilled form of the narrative.”

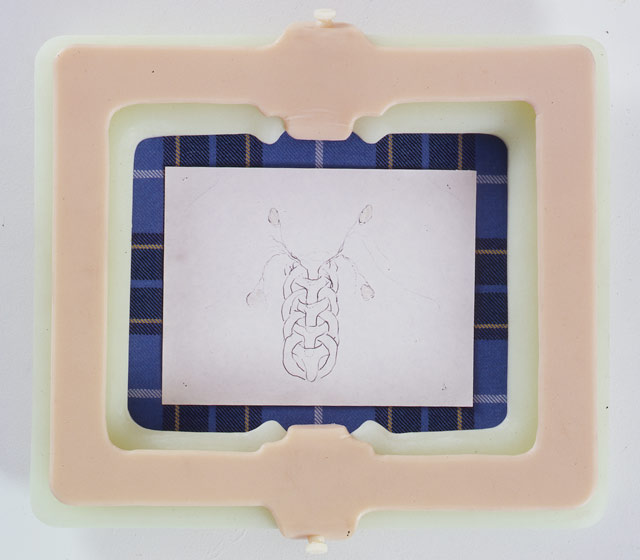

Matthew Barney, “Cremaster 4: Manx Manual,” graphite, lacquer, and petroleum jelly on paper in cast epoxy, prosthetic plastic, and Manx tartan, 1994-95 (copyright Matthew Barney / courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels)

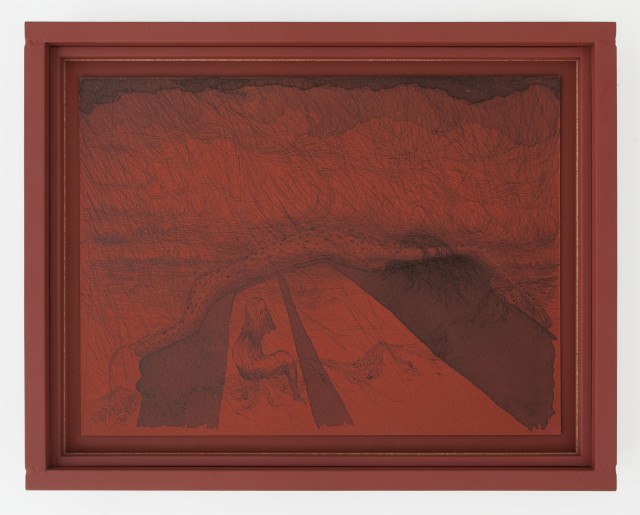

Hanging on the walls are fully realized ink and pencil drawings, several incorporating one of Barney’s signature materials, petroleum jelly, in self-lubricating plastic frames, that relate to such ambitious projects as the five-part Cremaster Cycle film series, which explores the ascending and descending muscle that determines gender; his Drawing Restraint performances, in which he creates art while limiting his physical mobility, one of which was recently held at the Morgan (the result of which can be seen in the Clare Eddy Thaw Gallery); the OTTOshaft trilogy, in which Barney uses Oakland Raiders center Jim Otto, who wore number 00, as the impetus for an exploration of athletic endurance that also involves Harry Houdini and the Hubris Pill; De Lama Lâmina (“From Mud, a Blade”), a collaboration with musician Arto Lindsay about environmental activist Julia Butterfly Hill; and River of Fundament, inspired by Norman Mailer’s Ancient Evening, which delves into the Egyptian belief of the soul’s death and rebirth as experienced by a 1967 Chrysler Crown Imperial. Barney’s most accomplished drawings are those done in red, comprising the “River Rouge” series, while his pieces on black are the most mysterious, the details visible from only certain angles.

Matthew Barney, “River Rouge: Crown Victoria,” ink on paper in painted steel frame, 2011 (copyright Matthew Barney / Courtesy Gladstone Gallery)

The show also includes vitrines filled with objects chosen specifically by Barney from his own collection as well as the Morgan’s that relate to his work, from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass to a Diane Arbus photo of Mailer, from a third-century papyrus copy of the Egyptian Book of the Dead to a page from a thirteenth-century book depicting sailors on the back of a whale, from the Goya drawing “Locura (Madness)” to Joseph Smith’s The Book of Mormon. In addition to adding insight into Barney’s ever-evolving narrative, they reveal his endless fascination with the human body. “The first pieces I made of Vaseline were about wanting to moisten something,” he told Gerald Matt in a 2008 interview. (The quote is included in the wall text for the 1991 drawing “Delay of Game [manual] C.”) “I was thinking of all things that I was making at the time as literally extensions of my body somehow, and I wanted these objects to feel like they had just come out of me or could be put into me.” In many ways, that gets to the heart of Barney’s intense creative process and intriguing, confusing, highly abstract, and extremely stylized output. While Barney might often physically restrain himself, the worlds he has brought to life, which have oozed out of him and into him, on paper, on film, and in live performance, seem to have no limits.