THE CONGRESS (Ari Folman,, 2013) + WORLD OF TOMORROW (Don Hertzfeldt, 2015)

Museum of the Moving Image, Redstone Theater

35th Ave. at 36th St., Astoria

Friday, February 24, $9-$15, 7:00

movingimage.us

The Museum of the Moving Image’s ongoing “Science on Screen” series continues February 24 with an intriguing pair of films that offer unique insight into what might be next. The evening begins with the first episode of Don Hertzfeldt’s seventeen-minute Oscar-nominated animated short World of Tomorrow, a series that began in 2015 and deals with cloning, time travel, digital consciousness, and immortality, featuring stick figures amid bold colors; young Emily is voiced by Hertzfeld’s four-year-old niece, Winona Mae, whose dialogue was recorded while she was playing. “We mustn’t linger,” future Emily (Julia Pott) tells younger Emily. “It is easy to get lost in memories.”

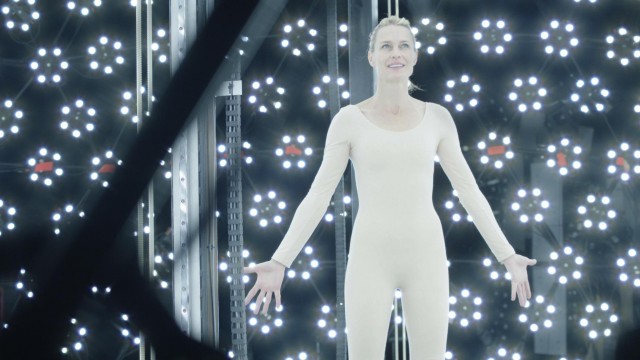

World of Tomorrow is followed by writer-director Ari Folman’s underrated 2013 live action/animated hybrid, The Congress, in which Folman imagines a sad but visually dazzling future. Inspired by Stanislaw Lem’s 1971 short novel The Futurological Congress, the film focuses on Robin Wright as a fictionalized version of herself, an idealistic actress about to turn forty-five who has let her career come second to raising her two children, daughter Sarah (Sami Gayle) and, primarily, son Aaron (Kodi Smit-McPhee), who is slowly losing the ability to see and hear. Wright’s longtime agent, Al (Harvey Keitel), has a last-chance opportunity for her: Jeff Green (Danny Huston), the head of Miramount, wants to scan her body and emotions so the studio can manipulate her digital likeness into any role while keeping her ageless. They don’t want the modern-day Robin Wright but the young, beautiful star of The Princess Bride, State of Grace, and Forrest Gump. The only catch is that in exchange for a substantial lump-sum payment, the real Wright will never be allowed to act again, in any capacity. With no other options, she reluctantly takes the deal. Twenty years later, invited to speak at the Futurological Congress, she enters a whole new realm, a fully animated world where men, women, and children live out their entertainment fantasies. Shocked by what she is experiencing, Wright meets up with Dylan Truliner (Jon Hamm), who has been animating her digital version for years, as a revolution threatens; meanwhile, Green has another offer for her, even more frightening than the first.

The Congress is a stunning examination of America’s obsession with celebrity culture and pharmaceutical release amid continuing technological advancements in which avatars can replace real people and computers can do all the work. The animated scenes, consisting of sixty thousand drawings made in eight countries, are mind-blowing, referencing the history of cartoons, from early Max Fleischer gems through Warner Bros. classics as well as nods to Disney, Pixar, Who’s Afraid of Roger Rabbit, and even Richard Linklater’s rotoscoped Waking Life; Folman also pays homage, directly and indirectly, to James Cameron and Stanley Kubrick. (The central part of the cartoon scenes were actually filmed live first, then animated based on the footage; be on the lookout for cameos by Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley, Frida Kahlo, and dozens of other familiar faces.)

Wright gives one of her best performances playing a modified version of herself, maintaining a calm, cool demeanor even as things threaten to completely break down around her. Paul Giamatti does a fine turn as her son’s concerned doctor, and Huston has a ball chewing the colorful scenery as the greedy, nasty studio head (as well as numerous other authority figures). The film also plays off itself in wonderful ways; the fictionalized Wright is at first against being scanned and used in science-fiction films, but the real Wright, of course, has agreed to be turned into a cartoon character in a science-fiction film. The story does get confusing in the second half, threatening to lose its thread as it goes all over the place, but Folman, whose previous film was the Oscar-nominated Waltz with Bashir, manages to bring it all together by the end, led by the stalwart Wright. Named Best European Animated Feature at the European Film Awards, The Congress is an eye-popping, soul-searching, hallucinogenic warning of what just might be awaiting all of us.