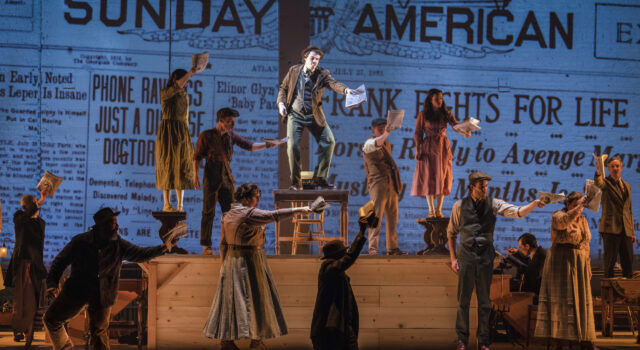

Lucille (Micaela Diamond) and Leo Frank (Ben Platt) fight for justice in Parade (photo by Joan Marcus)

PARADE

Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre

242 West 45th St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through August 6, $84-$288

paradebroadway.com

At intermission of the first Broadway revival of Parade, based on a true story of anti-Semitism, racism, and a terrible miscarriage of justice, several colleagues and I asked the same question: “Why is this a musical?” We found out in the far superior second act.

The show, directed by Harold Prince, with music and lyrics by Jason Robert Brown and a book by Oscar and Pulitzer Prize winner Alfred Uhry (Driving Miss Daisy), debuted at the Vivian Beaumont in 1998, running for thirty-nine previews and eighty-four regular performances, earning nine Tony nominations and winning for Best Book and Best Original Score. It is now playing at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre, in a version directed by Tony winner Michael Arden that transferred from Encores! at City Center and uses the 2007 Donmar Warehouse production, which included a few different songs from the original.

Parade begins with a prologue set in Marietta, Georgia, in 1862, as a young Confederate soldier (Charlie Webb) sings goodbye to his love and prepares to fight “for these old hills behind me / these old red hills of home. . . . in the land where honor lives and breathes.” The action then shifts to Atlanta in 1913, where the soldier (Howard McGillin), who lost a leg in the Civil War, is determined to help the South rise again, “honor” be damned.

It’s Confederate Memorial Day, and Lucille Frank (Micaela Diamond) wants to go on a picnic with her husband, Leo (Ben Platt), but he instead decides to go to work at the National Pencil Company, her father’s factory where Leo is superintendent. Thirteen-year-old Mary Phagan (Erin Rose Doyle) arrives to collect her pay and is later found murdered in the basement. The police arrest Leo for the crime, but he doesn’t take them very seriously, since he is innocent — but when power-hungry district attorney Hugh Dorsey (Paul Alexander Nolan) starts building a strong case against him, constructed on a series of lies, Leo suddenly faces reality as Lucille seeks to uncover the truth and reveal the conspiracy to railroad her husband.

Mary Phagan (Erin Rose Doyle) enjoys one final moment of life with Frankie Epps (Jake Pedersen) in based-on-fact musical (photo by Joan Marcus)

Among those participating in the frame-up led by Dorsey are National Pencil night watchman Newt Lee (Eddie Cooper), janitor Jim Conley (Alex Joseph Grayson), and Frank family maid Minnie McKnight (Danielle Lee Greaves), all of whom are Black and manipulated because of the color of their skin; Governor Jack Slaton (Sean Allan Krill), who is more concerned with his upcoming reelection campaign than the fate of one perhaps innocent man; Mary’s friend Frankie Epps (Jake Pedersen), who wants to see the murderer “burn in the ragin’ fires of hell forevermore”; right-wing newspaper editor and publisher Tom Watson (Manoel Felciano), who calls out, “Who’s gonna stop the Jew from killin’? Who’s gonna swing that hammer?”; Judge Roan (McGillin), who’d rather be fishing than in court; and Britt Craig (Jay Armstrong Johnson), an ambitious reporter who declares, “Take this superstitious city / Add one little Jew from Brooklyn / Plus a college education and a mousy little wife / And big news! Real big news! / That poor sucker saved my life!” Mary’s distraught mother (Kelli Barrett) is the only one considering forgiveness.

The focus of the show shifts dramatically after intermission, during which Leo remains onstage, in his jail cell, contemplating his fate; while the first act was all over the place, squeezing in too much information alongside oversized production numbers, the second act zeroes in on the touching relationship between Lucille and Leo as they desperately try to prove his innocence. It’s a beautiful, romantic love story, highlighted by a prison picnic Lucille brings to Leo in which she first chastises him for not accepting her assistance. “Do it alone, Leo — do it all by yourself. / You’re the only one who matters after all. / Do it alone, Leo — why should it bother me? / I’m just good for standing in the shadows / And staring at the walls, Leo,” she sings. Later they duet on “This Is Not Over Yet,” as Leo proclaims, “Hail the resurrection of / the south’s least fav’rite son! / It means I made a vow for better! / Two is better than one! / It means the journey ahead might get shorter. / I might reach the end of my rope! / But suddenly, loud as a mortar, there is hope!”

Parade features archival projections throughout (photo by Joan Marcus)

Dane Laffrey’s set is centered by a large wooden platform on which most of the action takes place, evoking a gallows as well as a coffin. There are scattered chairs and pews on either side, where many of the characters sit when they’re not in the scene, which can get confusing, especially for actors who play multiple roles. Susan Hilferty’s period costumes put us right in the 1910s, while Sven Ortel’s projections feature archival photographs of the real people and locations involved in the story, along with newspaper articles and a memorial plaque, a constant, and effective, reminder that this really happened — along with a final shot providing one last shock. Lauren Yalango-Grant and Christopher Cree Grant’s choreography thankfully calms down in the second half. Heather Gilbert’s lighting and Jon Weston’s sound maintains the dark mood surrounding the events. Music director and conductor Tom Murray handles three-time Tony winner Brown’s (The Last Five Years, Mr. Saturday Night) compelling score with a rousing touch, while director Michael Arden (Spring Awakening, Once on This Island) ably navigates through Uhry’s (Driving Miss Daisy, The Last Night of Ballyhoo) busy book. (Notably, Atlanta native Uhry’s great-uncle owned the National Pencil Company at the time of the killing.)

Tony winner Platt (Dear Evan Hansen, The Book of Mormon) and Diamond (The Cher Show, A Play Is a Poem) are wonderful together, portraying a Jewish couple in the Deep South facing bigotry; Platt captures Leo’s unrealistic belief that justice will triumph in the end, while Diamond embodies Lucille’s growth as she confronts what is happening in her beloved hometown. Grayson (Into the Woods, Girl from the North Country) brings down the house with “Feel the Rain Fall,” although, in 2023, it teeters on the edge of appropriation. Courtnee Carter (Once on This Island, Sing Street) as Angela and Douglas Lyons (Chicken & Biscuits, Beautiful) as Riley provide necessary perspective in their duet, “A Rumblin’ and a Rollin’,” in which they assert, “I can tell you this, as a matter of fact, / that the local hotels wouldn’t be so packed / if a little black girl had gotten attacked.” Also providing strong support are Cooper (Assassins, The Cradle Will Rock), Tony nominee Krill (Jagged Little Pill, Honeymoon in Vegas), and Greaves (Hairspray, Rent).

The final projection as the musical ends is a potent reminder that this country still has a long way to go when it comes to entrenched racism, misogyny, and anti-Semitism, in states such as Georgia and too many others that appear determined to continue a legacy of bigotry and hatred, although there is hope with such political stalwarts as Georgia senator Raphael Warnock, the reverend who tells us, before the show starts, to silence our cellphones but, implicitly, not our voices.