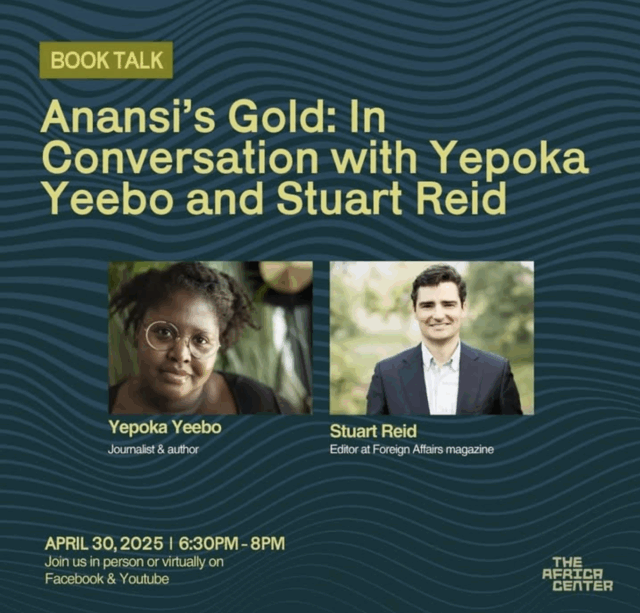

Lily Rabe and Billy Crudup star in Lincoln Center revival of Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts (photo by Jeremy Daniel)

GHOSTS

Lincoln Center Theater at the Mitzi E. Newhouse

150 West 65th St. between Broadway & Amsterdam Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through April 26, $98-$182.50

212-362-7600

www.lct.org

Lincoln Center Theater’s current revival of Ghosts, directed by three-time Tony winner Jack O’Brien from a new translation by Mark O’Rowe, begins with two actor/characters reading from the script, repeating lines with slight changes, as if rehearsing in front of the audience, before putting the pages away and starting the play proper. It’s an awkward start.

The play concludes, about 110 minutes later, with a painful, seemingly endless, overly melodramatic scene between a mother and her son, followed by the full cast returning their scripts to the center table. No, we did not just witness a dress rehearsal but a final presentation — one that seems to still need significant work.

In between is a clunky adaptation that is unable to capture the essence of Henrik Ibsen’s original 1881–82 morality tale, which has been seldom performed in New York, save for a Broadway run in 1982 and two versions at BAM, by Ingmar Bergman in 2003 and Richard Eyre in 2015.

The story unfolds on John Lee Beatty’s elegant dining room set. Painter Oswald Alving (Levon Hawke), the prodigal son, has returned home from Paris to his widowed mother, the businesslike Helena (Lily Rabe), who is in the process of signing over an orphanage to the church, represented by Pastor Manders (Billy Crudup). This man of the cloth has convinced Helena not to insure it because to do so would be evidence that she and the pastor “lack faith in God . . . in his divine protection.”

Oswald is attracted to the young maid, Regina (Ella Beatty), whose father, Jacob (Hamish Linklater), is a carpenter working for Mrs. Alving. Jacob’s goal is to open a classy boardinghouse for sailors on the mainland and have Regina join him there. Manders, who enjoys playing both sides against the middle, as if he knows things the others don’t and always has a secret up his sleeve, does not consider Jacob a man of the strongest character.

At one moment the pastor can praise someone, then tear them down in the next, as when he tells Helena, “Your impulses and desires have governed you all your life, Mrs. Alving. You’ve always resented authority and discipline, and as a result, you often rejected or ran away from things that were unpleasant to you. When being a wife became so, you abandoned your husband. When being a mother became so, you sent your son away to live with strangers … and as a result, you’ve become a stranger to him.”

A tragic event shifts the relationships as devastating facts explode all over.

Ghosts feels like a ghost of itself; while it has its moments, in the end nothing solid remains. The show merely dissipates into the air; failing to resonate today, it seems to get lost in the ether. The performances are uneven, and the conclusion is the final nail in the coffin.

Two couples face a possible apocalypse in Eric Bogosian’s Humpty Dumpty (photo by Matt Wells)

HUMPTY DUMPTY

The Chain Theatre

312 West Thirty-Sixth St. between Eighth & Ninth Aves., third floor

Wednesday – Sunday through May 3, $35

www.chaintheatre.org

Written in 2000 in the wake of the Y2K fears that life as we knew it on planet Earth would end, Eric Bogosian’s Humpty Dumpty is finally getting its New York City premiere, at the Chain Theatre; it’s easy to see what took so long.

Two couples have decided to take a break from their busy lives and head up to a vacation house in upstate New York, in the middle of nowhere. First to arrive are book editor Nicole (Christina Elise Perry) and her novelist husband, Max (Kirk Gostkowski); they are soon joined by Max’s best friend, successful screenwriter Troy (Gabriel Rysdahl), and his actress girlfriend, Spoon (Marie Dinolan). Occasionally stopping by is the property’s handyman, Nat (Brandon Hughes).

“No cable up here. And no fax machine anywhere. Cell phone barely works. And how do we do email?” Nicole complains. Max responds, “We don’t. That’s the point. For one week, we don’t do anything. No faxes. No email.”

They get a whole lot more than they bargained for when the power goes out for an extended period of time and the world outside threatens to turn into a battle zone they have no idea how to deal with, or with all the eggs that come their way.

Soon the five characters are at one another’s throats, but you’re not likely to care, as there’s nothing you’d rather do less than spend any time with these five annoying, self-absorbed nut cases. Because we have no affection for them in the first place, there’s no change in their development as the inexplicable and ever-more-confusing crisis worsens, just more of the same. And there’s not much director Ella Jane New can do on David Henderson’s cramped set.

When Max screams, “Troy, will you shut the fuck up!,” it’s too bad they all don’t listen.

Leonard Bernstein (Helen Schneider), waiter Michael (Victor Petersen), and Herbert von Karajan (Lucca Züchner) share an odd evening in Last Call (photo by Maria Baranova)

LAST CALL

New World Stages

340 West Fiftieth St. between Ninth & Tenth Aves.

Wednesday – Monday through May 4, $39-$159

lastcalltheplay.com

newworldstages.com

Peter Danish’s Last Call is a befuddling new play about an accidental meeting between a pair of giant maestros for the first time in decades. In 1988, American conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein (Helen Schneider) bumped into Austrian conductor Herbert von Karajan (Lucca Züchner) at the Blaue Bar in the Sacher Hotel. The eighty-year-old Karajan was in Vienna to conduct Brahms’s Symphony Number One “for the millionth time,” while the seventy-year-old Bernstein was there to receive “some silly award” — and attend his longtime colleague/rival’s concert. Within two years, they would both be dead.

Their fictionalized conversation was inspired by the recollections of the waiter who served them that night, named Michael (Victor Petersen) in the play, who shared the tale with Danish. Over the course of ninety slow-moving minutes, Bernstein, a Jew who composed such scores as On the Town, Wonderful Town, and West Side Story and conducted extensively with the New York Philharmonic and the Vienna Philharmonic, and Karajan, a onetime member of the Nazi Party who had long associations with the Berlin Philharmonic and London’s Philharmonia Orchestra, needle and praise each other relentlessly; Bernstein tells Michael that Karajan “is the second greatest conductor in the world,” while Karajan suggests that Bernstein, who has stopped conducting because of prostate issues, “could wear a diaper.”

Here’s a sample exchange regarding how Karajan has cut his intake to only one cigarette and one shot of whiskey a day:

Lenny: I find your restraint positively —

Herbert: Admirable? Impressive?

Lenny: Unbearable.

Herbert: It’s called discipline, Leonard! You should try it.

Lenny: Discipline? Oh, please! I speak six languages, play a dozen musical instruments, and have half the classical repertory committed to memory.

Herbert: Only half?

Lenny: Anyway, at this point in my life, I certainly don’t need a lecture about discipline! Look where all your discipline has gotten you! A half dozen strokes, crippling arthritis, bum kidneys!

That might very well be the best moment of the play, which otherwise grows laborious fast. Krajan and Michael occasionally speak in German, with the English translation projected onto a back wall, but it was very difficult to read from my seat. Turning the bar into a urinal — twice — made little sense, especially when the actors portraying the conductors stood way too close to the porcelain, which might be explained at least in part because those actors are both, inexplicably, women. Bernstein repeatedly refers to his fellow conductor as “von Karajan” when it should have been just “Karajan.” And director Gil Mehmert cannot get the actors and action in sync, failing to make the best use of Chris Barreca’s long, narrow set.

It should be last call for Last Call.

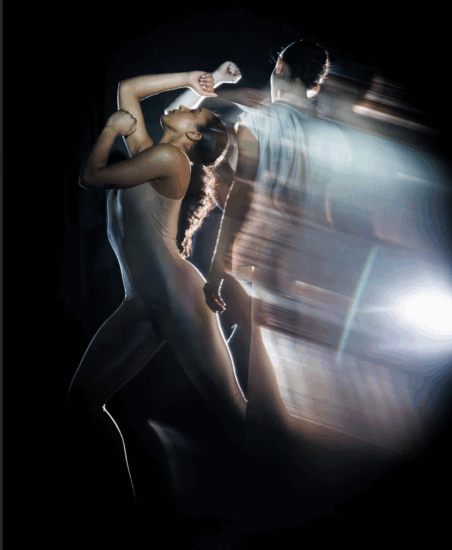

A cast of five tries to climb its way out of a deep hole in Redwood (photo by Matthew Murphy & Evan Zimmerman)

REDWOOD

Nederlander Theatre

208 West Forty-First St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through May 18, $99.75-$397

www.redwoodmusical.com

Idina Menzel’s heavily anticipated return to Broadway after a ten-year absence is a major disappointment, a vanity project that looks great but never achieves the necessary narrative flow.

Tony winner Menzel (Rent, Wicked) conceived of the show with Tony-nominated director Tina Landau (SpongeBob SquarePants, Superior Donuts), inspired by the true story of Julia Butterfly, the American activist who lived in a giant California redwood tree for more than two years in the late 1990s. Menzel stars as Jesse, a middle-aged woman in need of healing who is escaping her hectic life in New York City and an undisclosed tragedy and fleeing across the country. “I have to find somewhere else to be / where I’m no longer me,” she sings. “So I will drive down these broken lines / past the endless signs — keep on going —” And keep on going she does, with Menzel showing off her truly spectacular pipes, although it seems that Jesse’s wife, Mel (De’Adre Aziza), was left with no explanation, much like the audience at this point.

When she finally makes it to the Redwood Forest, she can’t stop annoying a pair of canopy botanists, Finn (Michael Park) and Becca (Khaila Wilcoxon), who are working there. Stilted explicative dialogue (Landau wrote the stultifying book, with lyrics by her and Kate Diaz) ensues, such as the following:

Jesse: Oh, well, um . . . wow, speaking of color . . . How did all these tree trunks become this . . . deep, deep black? Charcoal, onyx, jet, licorice —

Finn: Excuse me?

Jesse: Eigengraui! Bet you never heard of that color. Oh, it’s a game we play at work — who can think of the most synonyms for a particular descriptor. I always win. I’m better than a thesaurus.

Finn: The trees are black because they’ve been burned. Wildfires and prescribed fires. Did you know that redwoods are one of the most fire-resistant species in the world?

Becca: (To herself) And so it begins . . .

Finn: The bark on that tree is over a foot thick —

Becca: He’d lecture a rock if it listened.

Finn: (To Jesse) Yeah, it holds water, and protects the inner heartwood —

Jesse: Heartwood?

Finn: The wood at the center of the tree —

Jesse: The tree has a heart? Like a heart heart?

Finn: Except it’s dead.

Jesse: Dead?

Finn: The heartwood doesn’t carry water or nutrients anymore, but — it’s the strongest part of the tree.

Becca: This is part of the spiel he gives on his tours — you could sign up for one online in the spring — but right now, I’m so sorry, we really do have to get to work.

The plot goes back and forth between the past and the present, from Jesse and Mel’s first date to Jesse’s relationship with her son, Spencer (Zachary Noah Piser), attempting to explain how Jesse ended up in an off-limits tree in a California forest. References to Jewish sayings and prayers, such as Lo Tash’chit (“Do not destroy nature. You must feel for the trees as you do for humans.”) and Tikkun Olam (“repair the world”), bring the proceedings to a head-scratching halt. Plot holes grow so big that you can, well, fit a giant redwood through them.

However, the production can be spectacular, anchored by a huge tree in the center of Jason Ardizzone-West’s tilting set, surrounded by screens on which Hana S. Kim’s immersive projections transport the audience into the forest, all beautifully lit by Scott Zielinski. Mezzanine seating is suggested to take it all in, but even the visuals start to feel repetitive as the story becomes more and more stagnant. The fine cast, also hindered by Diaz’s overbearing score, can’t save the show, which is in need of big-time repairs.

BOOP! The Musical gets off to a great start before falling apart (photo by Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman)

BOOP! THE MUSICAL

Broadhurst Theatre

235 West Forty-Fourth St. between Broadway & Eighth Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through September 28, $58-$256

boopthemusical.com

BOOP! The Musical opens with a spectacular series of scenes in which Betty Boop (Jasmine Amy Rogers), the classic star of 1930s animated black-and-white shorts, is filming Betty Saves the Day, singing, “I may be one of Hollywood’s ‘It’ girls / But when there’s trouble afoot / This tiny tornado in spit and curls / Goes at it till the trouble’s kaput.” She works with her loyal director, Oscar Delacorte (Aubie Merrylees), and his assistant, Clarence (Ricky Schroeder), and enjoys spending time with her fellow cartoon characters Grampy (Stephen DeRosa), an eccentric Rube Goldberg–esque inventor, and his dog, Pudgy (a puppet operated by Phillip Huber).

When reporter Arnie Finkle (Colin Bradbury) asks her, “Who is the real Betty Boop?,” Betty suddenly begins examining her life. She tells Grampy, “It’s not something a girl like me has any right to complain about. I just . . . well, the attention is getting to be a little much. I’m not talking about men chasing me around a room with drool spilling out of their mouths. A good heavy frying pan takes care of them. I’m talking about being famous. People staring at me, taking my picture and wanting my autograph, or one of my shoes.” She adds, “I’ve played so many roles, I don’t know who I am anymore!”

Dreaming of spending one ordinary day as “Miss Nobody from Nowhere,” she sneaks into Grampy’s trans-dimensional tempus locus actuating electro-ambulator and finds herself at Comic Con 2025 in the Javits Center, where everything is in full color, including her. As she deals with the shock, she is helped by a kind man named Dwayne (Ainsley Melham) and superfan Trisha (Angelica Hale). Everyone breaks out into the roof-raising “In Color,” featuring dazzling costumes by Gregg Barnes, superb lighting by Philip S. Rosenberg and sound by Gareth Owen, fab projections by Finn Ross, and exciting choreography by two-time Tony winner Jerry Mitchell, who also directs. “It’s gonna lift you ten feet off the ground!” an attendee dressed as the Scarlet Witch proclaims, and that’s just how the audience feels as well, being lifted above David Rockwell’s terrific sets.

However, it all comes crashing down back to earth, and the rest of the show is a disappointing slog as the narrative falls apart and book writer Bob Martin, who cowrote Smash, decides the plot doesn’t have to make a bit of sense. Grampy propels himself and Pudgy into the color-future, where he reconnects with his lost love, Valentina (Faith Prince). Trisha brings Betty — now calling herself Betsy, not admitting she is the real Betty Boop — back to her house in Harlem, where she lives with her aunt Carol (Anastacia McCleskey) and her jazz-loving older brother, Dwayne. Carol is the campaign manager for the slimy Raymond Demarest (Erich Bergen), a mayoral candidate obsessed with sanitation. “When you think of solid waste, think Raymond Demarest” is one of his slogans.

Jokes repeat. Songs are unnecessary. Plot twists meander and confuse.

Yes, Max Fleischer’s original Betty Boop films might not have had the tightest scripts, but they had to fill seven minutes; the musical runs two and a half hours (with intermission) and, despite a lovely lead performance by Rogers in her Broadway debut, is unable to sustain itself, losing focus again and again, choosing style over substance, trying to stuff too much into a show that had tremendous potential.

Smash ends up being more of a dud on Broadway (photo by Matthew Murphy)

SMASH

Imperial Theatre

249 West 45th St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through January 4, $69-$321

smashbroadway.com

Is Smash a smash?

After seeing Smash on Broadway, I did some research on the 2012–13 series it is based on, which I had never watched. Created by Theresa Rebeck, who has written such plays as Seminar, Bernhardt/Hamlet, and I Need That, the NBC show offered a backstage look at the making of a musical based on Marilyn Monroe, called Bombshell, and featured a wide-ranging cast of theater performers, including Debra Messing, Christian Borle, Megan Hilty, Brian d’Arcy James, Jeremy Jordan, Leslie Odom Jr., Krysta Rodriguez, Will Chase, and Katharine McPhee. Rebeck got fired after the first season, and the program was canceled after the low-rated, problematic second season.

The criticisms about the Broadway musical that kept popping up in the reddit threads coalesced around major changes in the central plot, altering character motivations, keeping songs that were now irrelevant, and the inability to decide whether it is camp, a farce, or a more serious look at backstage shenanigans. Many fans also said they’d rather have seen Bombshell itself as a fully fledged Broadway musical instead of the current adaptation which they found undercooked and overwrought, in need of more tinkering and workshopping.

It wasn’t so much the content of the complaints that grabbed my attention as the general chaos they all alluded to and confirmed my thoughts that the Broadway Smash is a dud, a complete mess that is not ready for prime time on the Great White Way.

Robyn Hurder stars as Ivy Lynn, a Broadway fave who has been tapped to play Marilyn in Bombshell, which is being written by the married team of Tracy Morales (Krysta Rodriguez) and Jerry Stevens (John Behlmann) and directed and choreographed by Nigel Davies (Brooks Ashmanskas). Ivy Lynn’s longtime, loyal understudy is the extremely talented Karen Cartwright (Caroline Bowman), whose husband, Charlie (Casey Garvin), is playing Joe DiMaggio and likes to bring homemade cupcakes to the set; Nigel’s assistant, Chloe Zervoulian (Bella Coppola), is charged with trying to hold it all together; and producer Anita Molina Kuperman (Jacqueline B. Arnold) keeps her eyes on the budget, followed along by her social media assistant, Scott (Nicholas Matos).

It’s all thrown into disarray when Tracy and Jerry give Ivy Lynn a book on method acting by Susan Proctor (Kristine Nielsen), who Ivy Lynn hires as her coach; Susan, looking like a witch from The Crucible, convinces Ivy Lynn to remain in character 24/7 and whispers advice in ther ear, often contrary to what the director, cast, and crew are doing. As Ivy Lynn, who is popping pills Susan gave her, becomes more and more nasty and demanding, Karen spends more and more time in the limelight, along with Chloe, as they prepare for a critical dress rehearsal for investors and influencers.

The songs, by Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman, are repurposed from the TV series but often feel out of place here, with uninspiring orchestrations by Doug Besterman. The book, by Bob Martin and Rick Elice, lacks any kind of cohesion, as characters repeat themselves, relationships grow stale, subplots come and go, jokes about drinking and drugging are offensive, and, basically, most of what happens is hard to swallow, as Tony-winning director Susan Stroman has no chance of making any of it work and choreographer Joshua Bergasse can’t kick it into high gear.

No, Smash is no smash.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]