A Jewish family in Paris faces anti-Semitism in Joshua Harmon epic (photo by Matthew Murphy)

PRAYER FOR THE FRENCH REPUBLIC

Manhattan Theatre Club

MTC at New York City Center – Stage I

131 West 55th St. between Sixth & Seventh Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through March 27, $99

212-581-1212

www.manhattantheatreclub.com

“Why do they hate us?” a Jewish character asks near the end of Joshua Harmon’s extraordinary Prayer for the French Republic, which opened tonight at MTC at New York City Center – Stage I for a limited run (now extended through March 27). The playwright’s characters answer the question without being preachy or, perhaps even more important, preaching to the choir. In this three-hour multigenerational time-traveling epic, Harmon explores the centuries-old scourge of anti-Semitism with exquisite skill through the experiences of one family.

The play goes back and forth between 1944–46 and 2016–17, narrated by Patrick Salomon (Richard Topol), part of a long line of Salomons who have been in France for more than a thousand years. In his fifties, Patrick is part stage manager from Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, part Woody Allen from Annie Hall, watching and interacting with characters from the past and present.

In 2016, Molly (Molly Ranson), a twenty-year-old college student from America, has come to visit her distant cousins in Paris while studying abroad in Nantes. She arrives on a day when Daniel Benhamou (Yair Ben-Dor), the twenty-six-year-old son, comes home beaten and bloodied after an anti-Semitic attack. His mother, Marcelle Salomon Benhamou (Betsy Aidem), wants to call the police and take Daniel to the hospital, but he refuses. His father, Charles Benhamou (Jeff Seymour) — both parents are successful doctors — is calmer, carefully checking his son’s injuries.

Elodie (Francis Benhamou), Daniel’s brilliant manic-depressive older sister, is incensed that Marcelle blames Daniel’s thrashing on his unwillingness to cover his yarmulke. Elodie doesn’t think Jews should have to hide who they are, while Marcelle is more fearful of the consequences. “You put a huge target on your back!” Marcelle shouts. “Oh, so Daniel’s asking for it now? Is that seriously your argument? He’s asking for it?” Elodie asserts.

The play uses that as a jumping-off point, with scenes marked by full-throated disagreements, quiet allusions, and an astonishing amount of smoothly integrated analysis of Israel, religious and secular Jews, and Judaism in France through the ages, encompassing such events as the People’s Crusade in 1096, the Valentine’s Day massacre of 1349 in Strasbourg, and the 1960s postcolonial exodus of Algerian Jews to France. Set pieces incorporate discussions of Israeli and American Jews and the mass shootings at Charlie Hebdo, the Bataclan theater, and a kosher supermarket in Paris. The characters are troubled by the rise of Marine Le Pen and the National Front in France while considering the fate of the family’s last piano store, a legacy that goes back to 1855.

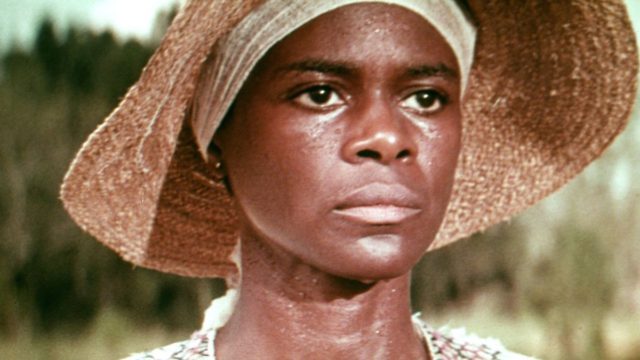

Irma (Nancy Robinette) and Adolphe Salomon (Kenneth Tigar) wonder where their children and grandchildren are in 1944 Paris (photo by Matthew Murphy)

The play is deeply rooted in history, presented in both monologues and flashbacks, particularly to the mid-1940s, when Marcelle’s great-grandparents, the elderly Irma Salomon (Nancy Robinette) and her husband, Adolphe (Kenneth Tigar), are living in Paris despite the occupation, not about to evacuate their home or give up the life they’ve built together. They worry every minute about the fate of their children, Jacqueline, Robert, and Lucien (Ari Brand), and their grandchildren, including Lucien’s son, Pierre Salomon (Peyton Lusk); Jacqueline escaped to Cuba, but Robert and Lucien are missing.

As Irma and Adolphe, who runs the piano business, sit at the dinner table, Patrick wonders about his great-grandparents. “What were they like, as people?” he asks. “What did they talk about? I have to imagine it was hard not to talk about their children, their grandchildren. . . .” Irma responds as if Patrick is right there with them: “We don’t talk about our children that much.” Adolphe then regales his wife with a beautiful fairy tale in which every member of their family is happy, healthy, and safe, an unlikely fantasy.

Over the course of three hours (with two intermissions), Patrick, the son of a Catholic mother and nonreligious Jewish father, wanders between eras, sharing what details he knows, singing at the Salomon piano that his sister Marcelle inherited, and occasionally participating in the modern-day moments, highlighted by a Passover Seder that turns ugly fast.

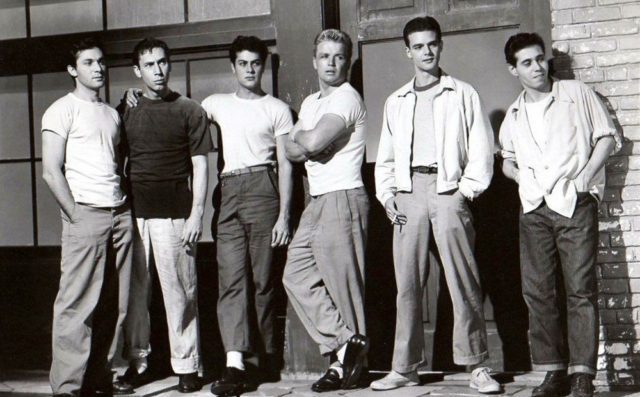

Molly (Molly Ranson), Charles (Jeff Seymour), and Daniel (Yair Ben-Dor) make sufganiyot together in world premiere play from MTC (photo by Matthew Murphy)

Terrorism and fear are perpetually on their minds. In an early exchange, Molly, who represents the current battle over BDS and other Israel-related issues on American college campuses, and Marcelle, who represents, well, one of my mother’s best friends, get into it.

Molly: My parents didn’t want me to come to France at all, but . . .

Marcelle: Why not?

Molly: Just cause of all the, you know. The terrorism.

Marcelle: There’s terrorism everywhere.

Molly: That’s what I said, but they were scared.

Marcelle: Aren’t you from New York? What’s to be scared?

Molly: I agree.

Marcelle: The whole world has terrorism now. There’s nowhere to hide. Either you live in the world, or you live in a cave. Personally, I don’t want to be a caveman.

Charles, whose family escaped Algeria when it became too dangerous, admits, “I’m scared, Marcelle. You lay everything out, you lay it out so rationally, and I hear every word you’re saying, but, I’m scared. We are Jews. We are Jews. The only reason we’re still on this planet is because we learned to get out of dangerous situations before they got the better of us. Something is happening in the world, and it’s happening in our country too — I can feel it.” When he says “our country too,” it’s impossible not to think about how it’s happening in America today, with brutal assaults on Jews from Pittsburgh, Boise, and New York City to Colleyville, St. Petersburg, and Poway.

Francis Benhamou brings down the house in a dazzling monologue when Elodie, in a bar with Molly, rants and rages about American Judaism and misperceptions about Israel. “American Jews . . . feel pretty free,” she explains in a verbal barrage. “So when it comes to Israel, they either despise it, or they’re slavishly devoted to it because they have a deep-seated understanding in their bones that there has never been a country on Earth that hasn’t eventually at some point turned on its Jews, and even in America, that fate awaits them too. Then you have the American Jew who hates Israel or is highly critical of Israel and I would argue part of why they feel able to be so critical of Israel is because they feel so safe in America, because they’ve convinced themselves that they can stay in America forever and maybe that’s true now but if history is our guide and history must always be our guide then you have to ask, so you feel safe today but will that be the case a hundred years from now? Or ten?” It’s a discussion I know I’ve had many times with friends and relatives, and Harmon nails it.

Narrator Patrick Salomon (Richard Topol) goes back and forth in time in Prayer for the French Republic (photo by Matthew Murphy)

Takeshi Kata’s elegant set rotates between the Benhamous’ lovely home and the Salomons’ less-fashionable wartime apartment. Tony, Drama Desk, and Obie–winning director David Cromer, who mounted a groundbreaking adaptation of Our Town on Broadway in 2009 (as well as helming The Band’s Visit, The Sound Inside, Tribes, and many other well-regarded shows), seamlessly integrates the two eras, which are often onstage together, one in the background of the other like a ghost, with superb lighting by Amith Chandrashaker and sound by Lee Kinney and Daniel Kluger.

The cast is uniformly outstanding, with Topol’s (Anatomy of a Suicide, The Normal Heart) naturally calm, likable demeanor alleviating some of the palpable tension until there’s no stopping it; Topol previously starred as Lemml, the immigrant stage manager and narrator, in Paula Vogel’s Tony-nominated Indecent, about the making of Sholem Asch’s controversial 1907 Yiddish play, God of Vengeance. Ranson imbues Molly with an inner strength and confidence that has her going toe-to-toe with her cousins, who have a tendency to be loud and forceful; Ranson similarly portrayed Melody, Liam’s (Michael Zegen) shiksa goddess, in Harmon’s Bad Jews, which also dealt with the Holocaust and family legacy. Ranson and Ben-Dor have an immediate chemistry as they balance fighting and flirtation.

Even Daniel’s fondness for Bob Dylan is no mere affectation, as the Nobel- and Pulitzer-winning troubadour famously went from being Jewish to a born-again Christian and back to Jewish during his fabled career; his 1983 album, Infidels, features several songs about Israel.

But it’s Harmon’s (Significant Other, Admissions) impeccable dialogue and razor-sharp characterizations that take center stage. Every word, every action rings true and hits home; he gets the Jewish American experience just right, even if this is a Parisian family (that speaks English without the hint of a French accent). I’ve been involved in these arguments and know these people well; I’m planning on memorizing a bunch of lines in time for this year’s Seders.