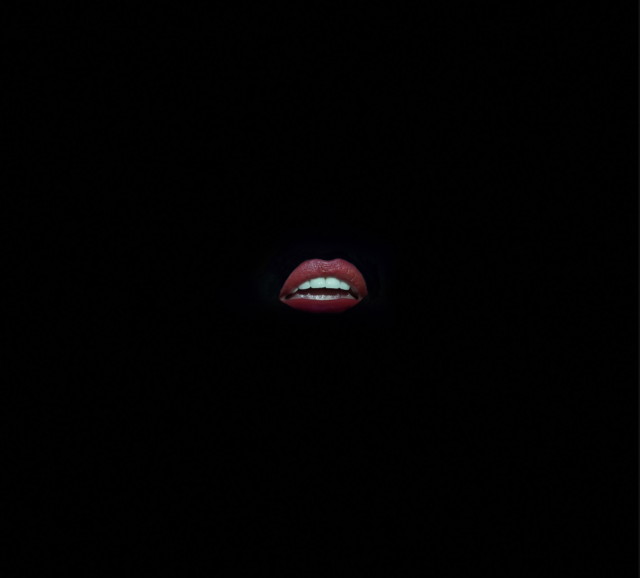

Sarah Street’s mouth is the star of the first of three short Beckett plays at Irish Rep (photo by Carol Rosegg)

BECKETT BRIEFS: FROM THE CRADLE TO THE GRAVE

Irish Repertory Theatre, Francis J. Greenburger Mainstage

132 West Twenty-Second St. between Sixth & Seventh Aves.

Wednesday – Sunday through March 9, $60-$125

212-727-2737

irishrep.org

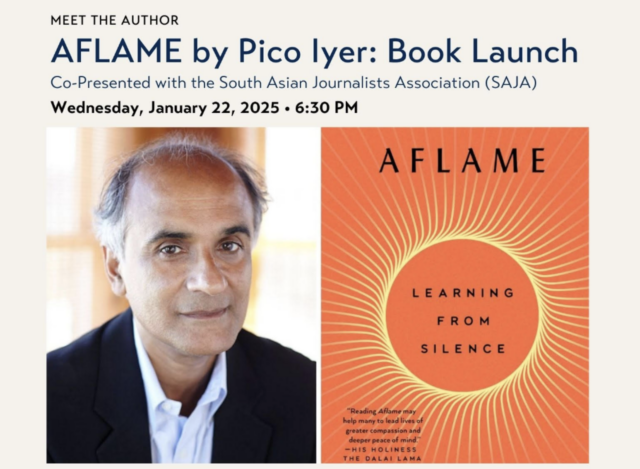

Why is the Irish Rep presenting Beckett Briefs: From the Cradle to the Grave, three short works by Samuel Beckett, now? “Because he’s Irish, and he knows things,” Irish Rep artistic director Charlotte Moore and producing director Ciarán O’Reilly explain in a program note.

The Dublin-born playwright died in Paris in 1989 at the age of eighty-three, during the Irish Rep’s second season, in which they staged Chris O’Neill and Vincent O’Neill’s one-man Endworks, based on more than a dozen Beckett plays. The company has since performed Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape in 1998, Endgame in 2005 and 2023, A Mind-Bending Evening of Beckett in 2013 featuring Act without Words, Play, and Breath, and Bill Irwin’s solo show On Beckett in 2018, 2020, and 2024.

In his unique, existential writings, Beckett displayed a flair for knowing things, although it is usually not easy to parse out exactly what he means, a significant part of the joy of experiencing his plays, which also include the full-length All That Fall, Happy Days, and Waiting for Godot. Theater itself is a regular subject; his scripts have extremely detailed instructions of nearly every movement, costume, and prop, and the narratives are often about the art of storytelling.

Such is the case with Beckett Briefs, a trio of tales about life, death, and the afterlife in which the narrative style drives the work.

First up is Not I, Beckett’s 1972 monologue that has been performed by Beckett muse Billie Whitelaw, Jessica Tandy, Julianne Moore, Lisa Dwan, and British comedian Jess Thom, who incorporated her copralalia (cursing) form of Tourette’s syndrome into her delivery of the nonstop barrage of text. The play generally runs between nine and fifteen minutes; it is not a race, but the actor is expected to go through the 2,268 words as fast as possible. “I am not unduly concerned with intelligibility. I hope the piece may work on the nerves of the audience, not its intellect,” Beckett wrote in a 1972 letter to Tandy prior to the play’s world premiere at Lincoln Center.

A hole has been cut in a black curtain more than eight feet above the stage, so the only thing we can see is a mouth peeking through, in this case belonging to Irish Rep regular Sarah Street. Her teeth are sparkling white and her red lipstick thick and emotive — resembling the famous movie poster for The Rocky Horror Picture Show — as she speeds through Beckett’s wildly unpredictable verbiage, barely stopping to breathe. Known as Mouth, the character has been mostly speechless since her parents died when she was an infant, but now, at the age of seventy, words start pouring out of her.

The audience is not meant to understand every plot detail as she relates stories involving shopping in a supermarket, going to court, sitting on a mound in Croker’s Acres, and searching for cowslips in a field, bringing up such concepts as shame, torment, sin, pleasure, and guilt. The protagonist has suffered an unnamed trauma that has led to her becoming an outcast from society and virtually unable to communicate with others. In many ways, she is as surprised at what she’s saying as we are at what we are hearing. For example:

“imagine! . . . whole body like gone . . . just the mouth . . . lips . . . cheeks . . . jaws . . . never . . . what? . . . tongue? . . . yes . . . lips . . . cheeks . . . jaws . . . tongue . . . never still a second . . . mouth on fire . . . stream of words . . . in her ear . . . practically in her ear . . . not catching the half . . . not the quarter . . . no idea what she’s saying . . . imagine! . . no idea what she’s saying! . . and can’t stop . . . no stopping it . . . she who but a moment before . . . but a moment! . . could not make a sound . . . no sound of any kind . . . now can’t stop . . . imagine! . . can’t stop the stream . . . and the whole brain begging . . . something begging in the brain . . . begging the mouth to stop . . . pause a moment . . . if only for a moment . . . and no response . . . as if it hadn’t heard . . . or couldn’t . . . couldn’t pause a second . . . like maddened . . . all that together . . . straining to hear . . . piece it together . . . and the brain . . . raving away on its own . . . trying to make sense of it . . . or make it stop . . .”

O’Reilly, the director of all three parts of Beckett Briefs, has excised the second character, known as the Auditor, who in some renderings stands off to the side of the stage, hidden in the shadows. (In Thom’s case, the Auditor served as ASL translator.) So the focus is completely on the mouth in a dazzling performance by Street, a celebration of language and a potent reminder that life is to be lived, not merely watched or listened to, that there is more to our existence, even beyond theater.

Sarah Street, Roger Dominic Casey, and Kate Forbes examine their love triangle in Beckett’s Play (photo by Carol Rosegg)

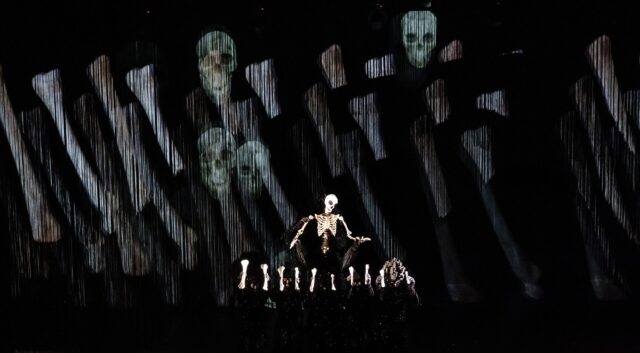

In Endgame, a married couple named Nell and Nagg live in garbage cans. In Play, the middle section of Beckett Briefs, three people find themselves in urns in the afterlife, only their heads and the outlines of the vessels visible. A man (Roger Dominic Casey) appears to be doomed for eternity to be trapped between his wife (Kate Forbes) and his mistress (Street). They look straight ahead “undeviatingly,” the script says, and speak only when a spotlight shines on them.

Their initial exchange sets the stage of this forever love triangle.

W1: I said to him, Give her up. I swore by all I held most sacred —

W2: One morning as I was sitting stitching by the open window she burst in and flew at me. Give him up, she screamed, he’s mine. Her photographs were kind to her. Seeing her now for the first time full length in the flesh I understood why he preferred me.

M: We were not long together when she smelled the rat. Give up that whore, she said, or I’ll cut my throat — [Hiccup.] pardon — so help me God. I knew she could have no proof. So I told her I did not know what she was talking about.

W2: What are you talking about? I said, stitching away. Someone yours? Give up whom? I smell you off him, she screamed, he stinks of bitch.

W1: Though I had him dogged for months by a first-rate man, no shadow of proof was forthcoming. And there was no denying that he continued as . . . assiduous as ever. This, and his horror of the merely Platonic thing, made me sometimes wonder if I were not accusing him unjustly. Yes.

M: What have you to complain of? I said. Have I been neglecting you? How could we be together in the way we are if there were someone else? Loving her as I did, with all my heart, I could not but feel sorry for her.

It’s a tour de force for Casey (Aristocrats, CasablancaBox), Forbes (A Touch of the Poet, Rubicon), and Street (Molly Sweeney, Belfast Girls) as well as lighting designer Michael Gottlieb and sound designers M. Florian Staab and Ryan Rumery, who must be in perfect sync and not miss a beat as the spotlight switches from face to face in the snap of a finger, sometimes illuminating all three characters at the same time. Occasionally the light grows dim, signaling the actors to slow down. As with Not I, it is not a race, but it leaves the audience breathless, as if we had just finished running laps.

Everything slows down in the finale, Krapp’s Last Tape, but that doesn’t mean it is any easier to decipher. The set, by Irish Rep genius Charlie Corcoran, is a dark, messy room with overstuffed shelves, a desk with an old-fashioned reel-to-reel tape player and several canisters on it, and a light fixture with a single bulb dangling overhead. The unkempt, disheveled Krapp (F. Murray Abraham) shuffles around the floor, struggles to open one of the drawers in the front, and takes out a banana, which he fondles before eating it, tossing the peel to his right. Beckett, a vaudeville fan, does indeed have Krapp slip on it. Krapp, occasionally letting out tired grunts of woe, then opens the second drawer, takes out another banana, peels it, and puts it in his mouth, being more careful this time with the peel. However, he decides not to eat the banana, instead putting it in his pocket.

An aging man (F. Murray Abraham) looks back at his younger self in Krapp’s Last Tape (photo by Carol Rosegg)

He goes in the back and returns with a large ledger that he looks through, reading out loud, “Box . . . thrree . . spool five. Spool! Spooool!” He finds the box he needs, starts playing the recording, then sweeps everything else off the desk and onto the floor. He has chosen to listen to a memory of his thirty-ninth birthday, his young self explaining, “Thirty-nine today, sound as a bell, apart from my old weakness, and intellectually I have now every reason to suspect at the . . . crest of the wave — or thereabouts. Celebrated the awful occasion, as in recent years, quietly at the Winehouse. Not a soul. Sat before the fire with closed eyes, separating the grain from the husks. Jotted down a few notes, on the back of an envelope. Good to be back in my den, in my old rags. Have just eaten I regret to say three bananas and only with difficulty refrained from a fourth. Fatal things for a man with my condition. Cut’em out! The new light above my table is a great improvement. With all this darkness round me I feel less alone. In a way. I love to get up and move about in it, then back here to . . . me. Krapp.”

It doesn’t appear that much has changed over the last three decades, Krapp still alone, still eating bananas, still surrounded by darkness. As the tape continues, Krapp scampers off to take a few gulps from a bottle of liquor, looks up the meaning of “viduity,” sings, and recalls a romantic evening on a lake. But the tape does not provide him with happiness; he barks out, “Just been listening to that stupid bastard I took myself for thirty years ago, hard to believe I was ever as bad as that. Thank God that’s all done with anyway.”

The autobiographical, poetic Krapp’s Last Tape was written in 1958 for Patrick Magee and has also been performed by Harold Pinter, Brian Dennehy, Michael Gambon, and, primarily, John Hurt, who brought it to the 2011 BAM Next Wave Festival. Oscar and Obie winner and Emmy and Grammy nominee Abraham (Good for Otto, It’s Only a Play), who is eighty-five, fully inhabits the role of a man long past the crest of the wave. The desk is near the front of the stage, so close to the audience that you can practically reach out and touch him, although you’re probably inclined to stay away from such a dour, sad, disheveled person.

All three plays, which total about seventy-five minutes, deal with time, memory, and the futility of language, as each character faces issues with communication yet delivers masterful articulation. Expertly directed by O’Reilly (Endgame, The Emperor Jones), Beckett Briefs is a vastly entertaining evening that immerses you in the unique, engaging, complex, and minimalistic worlds the playwright is renowned for, enigmatic works that are worth revisiting over and over again, offering new and fascinating insights as viewers age and understand them in ever-changing, profound ways.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]