PHOENIX (Christian Petzold, 2014)

Film Society of Lincoln Center, Walter Reade Theater

165 West 65th St. between Eighth Ave. & Broadway

Saturday, December 1, 6:45 (introduced by director)

Sunday, December 9, 6:30

Festival runs November 30 – December 13

212-875-5610

www.filmlinc.org

www.ifcfilms.com

In conjunction with the release of Christian Petzold’s latest film, The State I Am In, the Film Society of Lincoln Center is presenting the two-week series “The State We Are In,” consisting many of the German filmmakers’ previous works, including early television movies, as well as films that influenced him. Screening on December 1 at 6:45 (introduced by Petzold) and December 9 at 6:30, 2014’s Phoenix is a mesmerizing noir set in 1945 Berlin, where an Auschwitz survivor tries to reestablish her identity, but going home turns into a strange, painful, and dangerous journey. Nina Hoss is riveting as Nelly Lenz, a nightclub singer who is the only member of her family to have made it out of the war alive. Reentering Germany from Switzerland, she seems like a ghost or a mummy, her face swathed in bandages after having been severely disfigured by a gunshot wound. Wealthy enough to afford special facial reconstruction surgery, she is offered the chance to look like anyone she wants; the doctor gently suggests an entirely new appearance would be best, but she defiantly demands her own face back. Cared for by a companion, Lene Winter (Nina Kunzendorf), a fellow Jew who helps Holocaust survivors and wants to move to Palestine with her, Nelly seems psychologically frozen, tentative and frightened of the future. Instead of looking forward, she decides to go back to her non-Jewish husband, Johnny (Ronald Zehrfeld), now called Johannes. He has disowned his past so thoroughly that he doesn’t recognize Nelly as his wife, returned from the concentration camp, instead believing her to be a survivor who resembles her just enough to enable him to cash in on Nelly’s inheritance. As he grooms her to walk and talk like Nelly, reminiscent of what Jimmy Stewart does to Kim Novak in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, she begins finding out things about him that are deeply troubling, including the nightmarish possibility that he might have been the one who betrayed her to the Nazis.

In conjunction with the release of Christian Petzold’s latest film, The State I Am In, the Film Society of Lincoln Center is presenting the two-week series “The State We Are In,” consisting many of the German filmmakers’ previous works, including early television movies, as well as films that influenced him. Screening on December 1 at 6:45 (introduced by Petzold) and December 9 at 6:30, 2014’s Phoenix is a mesmerizing noir set in 1945 Berlin, where an Auschwitz survivor tries to reestablish her identity, but going home turns into a strange, painful, and dangerous journey. Nina Hoss is riveting as Nelly Lenz, a nightclub singer who is the only member of her family to have made it out of the war alive. Reentering Germany from Switzerland, she seems like a ghost or a mummy, her face swathed in bandages after having been severely disfigured by a gunshot wound. Wealthy enough to afford special facial reconstruction surgery, she is offered the chance to look like anyone she wants; the doctor gently suggests an entirely new appearance would be best, but she defiantly demands her own face back. Cared for by a companion, Lene Winter (Nina Kunzendorf), a fellow Jew who helps Holocaust survivors and wants to move to Palestine with her, Nelly seems psychologically frozen, tentative and frightened of the future. Instead of looking forward, she decides to go back to her non-Jewish husband, Johnny (Ronald Zehrfeld), now called Johannes. He has disowned his past so thoroughly that he doesn’t recognize Nelly as his wife, returned from the concentration camp, instead believing her to be a survivor who resembles her just enough to enable him to cash in on Nelly’s inheritance. As he grooms her to walk and talk like Nelly, reminiscent of what Jimmy Stewart does to Kim Novak in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, she begins finding out things about him that are deeply troubling, including the nightmarish possibility that he might have been the one who betrayed her to the Nazis.

Tense and unnerving, Phoenix was inspired by Alexander Kluge’s An Experiment in Love, Hubert Monteilhet’s Return from the Ashes, Harun Farocki’s “Switched Women,” and oral histories from the Shoah Foundation. (Farocki, who passed away in July 2014, collaborated with Petzold on the screenplay.) Hoss and Zehrfeld, who previously worked together in Petzold’s gripping 2012 psychological thriller, Barbara, have an appropriately uneasy chemistry, keeping things off balance as former lovers who pursue an unusual courtship, he unwilling to acknowledge what’s right in front of him, she desperate to be recognized for who she was, and is. It’s a kind of eerie cat-and-mouse game, with more than a touch of Stockholm Syndrome, that intelligently examines a fascinating German amnesia about the war and its victims on a very personal scale. Kunzendorf (Scene of the Crime, Years of Love) is excellent as Lene, a forward-thinking woman who wants to start a new life with Nelly yet is unable to drag her away from her obsession with Johnny, while Zehrfeld (Finsterworld) has just the right amount of trepidation as Johnny pursues his selfish goal. But Hoss, in her sixth film with Petzold (Jerichow, Something to Remind Me), is simply extraordinary, her every movement utterly captivating, portraying complex emotions with remarkable skill. And the ending is simply brilliant, unforgettable. Once it gets past a few minor incongruities, Phoenix rises high, a spellbinding story of a twisted relationship in 1945 Germany that calls upon ancient myth, modern psychology, a nation’s guilt, and love and longing for the past to evoke universal themes — while posing some very difficult questions for everyone.

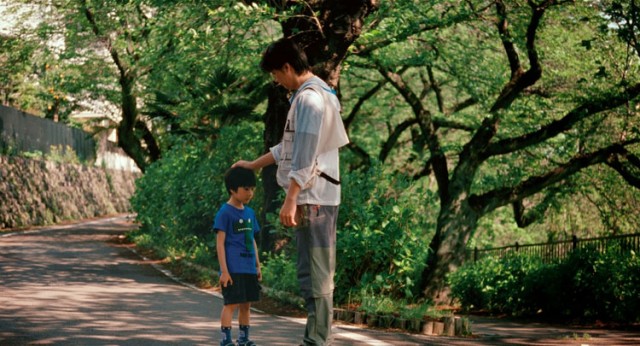

Andre (Ronald Zehrfeld) and Barbara (Nina Hoss) try to retain their humanity under difficult conditions in 1980 East Germany

BARBARA (Christian Petzold, 2012)

Film Society of Lincoln Center, Walter Reade Theater

Tuesday, December 11, 7:00, and Thursday, December 13, 9:00

www.adoptfilms.net

Christian Petzold’s Barbara is a gripping, eerily slow-paced psychological thriller that explores fear, paranoia, and responsibility. Nina Hoss, in her fifth film with writer-director Petzold, gives a subtly powerful performance as Barbara Wolff, an East German doctor who has been shipped off by the government to a country hospital run by Andre (Ronald Zehrfeld). It is 1980, and Barbara has done something to get on the GDR watch list, causing her to be under near-constant surveillance. She carefully looks around everywhere she goes, wondering if the woman on the bus, the man out for a smoke, or the person on the pay phone is working for the Stasi. She is most suspicious of Andre as he attempts to get close to her, asking her personal questions and trying to spend more and more time with her. Meanwhile, Barbara has secret meetings with various people, including her West German lover, Jörg (Mark Waschke), who wants to get her out of the east. But as much as Barbara wants to live a free and open life, she is also a dedicated doctor who has become attached to two patients: Stella (Jasna Fritzi Bauer), a pregnant woman who does not want to be sent back to a labor camp, and Mario (Jannik Schümann), who has suffered a potentially fatal head injury following a suicide attempt. Petzold (Something to Remind Me, Wolfsburg, Yella), inspired by the likes of Claude Chabrol, To Have and Have Not, and The French Connection, drapes Barbara in a compulsive feeling of paranoia and dread, creating a blanketing atmosphere of mystery and imminent danger in which one wrong move can result in capture, imprisonment, or worse. Wrapped in a cloak of suspicion, Barbara evokes for the viewer what living in 1980 East Germany might have been like. The complex relationship between Barbara and Andre is handled with great skill by Petzold, balancing their individual needs with their responsibilities to their profession and the state. Germany’s official submission for the 2012 Best Foreign Language Film, Barbara is a tense tale that examines the cold war in unique and fascinating ways. It is screening on December 11 at 7:00 and December 13 at 9:00 in “The State We Are In,” which features such other Petzold works as Pilots, Cuba Libre, The Sex Thief, Something to Remind Me, Ghosts, and Jerichow in addition to works he selected, including François Truffaut’s The Woman Next Door, Vincente Minnelli’s Some Came Running, Xavier Beauvois’s The Young Lieutenant, and John Berry’s He Ran All the Way with Jean Renoir’s A Day in the Country; Petzold will be on hand for several introductions and Q&As.

Christian Petzold’s Barbara is a gripping, eerily slow-paced psychological thriller that explores fear, paranoia, and responsibility. Nina Hoss, in her fifth film with writer-director Petzold, gives a subtly powerful performance as Barbara Wolff, an East German doctor who has been shipped off by the government to a country hospital run by Andre (Ronald Zehrfeld). It is 1980, and Barbara has done something to get on the GDR watch list, causing her to be under near-constant surveillance. She carefully looks around everywhere she goes, wondering if the woman on the bus, the man out for a smoke, or the person on the pay phone is working for the Stasi. She is most suspicious of Andre as he attempts to get close to her, asking her personal questions and trying to spend more and more time with her. Meanwhile, Barbara has secret meetings with various people, including her West German lover, Jörg (Mark Waschke), who wants to get her out of the east. But as much as Barbara wants to live a free and open life, she is also a dedicated doctor who has become attached to two patients: Stella (Jasna Fritzi Bauer), a pregnant woman who does not want to be sent back to a labor camp, and Mario (Jannik Schümann), who has suffered a potentially fatal head injury following a suicide attempt. Petzold (Something to Remind Me, Wolfsburg, Yella), inspired by the likes of Claude Chabrol, To Have and Have Not, and The French Connection, drapes Barbara in a compulsive feeling of paranoia and dread, creating a blanketing atmosphere of mystery and imminent danger in which one wrong move can result in capture, imprisonment, or worse. Wrapped in a cloak of suspicion, Barbara evokes for the viewer what living in 1980 East Germany might have been like. The complex relationship between Barbara and Andre is handled with great skill by Petzold, balancing their individual needs with their responsibilities to their profession and the state. Germany’s official submission for the 2012 Best Foreign Language Film, Barbara is a tense tale that examines the cold war in unique and fascinating ways. It is screening on December 11 at 7:00 and December 13 at 9:00 in “The State We Are In,” which features such other Petzold works as Pilots, Cuba Libre, The Sex Thief, Something to Remind Me, Ghosts, and Jerichow in addition to works he selected, including François Truffaut’s The Woman Next Door, Vincente Minnelli’s Some Came Running, Xavier Beauvois’s The Young Lieutenant, and John Berry’s He Ran All the Way with Jean Renoir’s A Day in the Country; Petzold will be on hand for several introductions and Q&As.

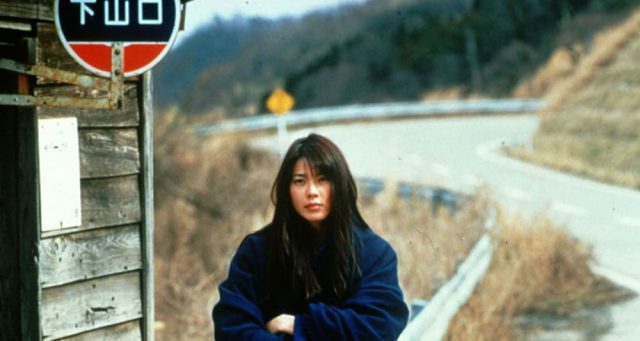

To celebrate the theatrical release of Japanese auteur Hirokazu Kore-eda’s latest work, Shoplifters, the Palme d’Or winner that opens November 23, the Film Society of Lincoln Center is presenting six of the master’s earlier tales, concentrating on his exquisite depiction of family life. Running November 19-22, the mini-festival provides a terrific entry into the oeuvre of Kore-eda, a visionary who tells a story like no one else. “Six by Kore-eda” begins with his first fiction film, Maborosi, which followed three documentaries (Lessons from a Calf, However . . . , August without Him). After Yumiko’s husband, Ikuo (Tadanobu Asano), mysteriously commits suicide, she (Makiko Esumi) gets remarried and moves to her new husband’s (Takashi Naitō) small seaside village home with her son (Gohki Kashima), where she begins to put her life back together. This stunning film is marvelously slow-paced, lingering on characters in the distance, down narrow alleys, across gorgeous horizons, with very little camera movement by cinematographer Masao Nakabori. Maborosi, the only one of his films he didn’t write — the screenplay is by Yoshihisa Ogita, based on the novel by Teru Miyamoto — is a stunning debut from one of the leading members of Japan’s fifth generation. It is screening at the Walter Reade Theater on November 19 at 6:30 and November 22 at 9:00

To celebrate the theatrical release of Japanese auteur Hirokazu Kore-eda’s latest work, Shoplifters, the Palme d’Or winner that opens November 23, the Film Society of Lincoln Center is presenting six of the master’s earlier tales, concentrating on his exquisite depiction of family life. Running November 19-22, the mini-festival provides a terrific entry into the oeuvre of Kore-eda, a visionary who tells a story like no one else. “Six by Kore-eda” begins with his first fiction film, Maborosi, which followed three documentaries (Lessons from a Calf, However . . . , August without Him). After Yumiko’s husband, Ikuo (Tadanobu Asano), mysteriously commits suicide, she (Makiko Esumi) gets remarried and moves to her new husband’s (Takashi Naitō) small seaside village home with her son (Gohki Kashima), where she begins to put her life back together. This stunning film is marvelously slow-paced, lingering on characters in the distance, down narrow alleys, across gorgeous horizons, with very little camera movement by cinematographer Masao Nakabori. Maborosi, the only one of his films he didn’t write — the screenplay is by Yoshihisa Ogita, based on the novel by Teru Miyamoto — is a stunning debut from one of the leading members of Japan’s fifth generation. It is screening at the Walter Reade Theater on November 19 at 6:30 and November 22 at 9:00