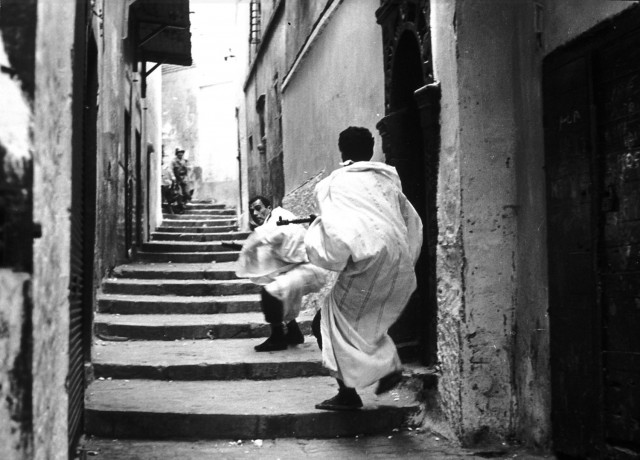

Documentary reveals how Elizabeth Streb and her Extreme Action Company (including Jackie Carlson, seen here) take dance to a whole new level

BORN TO FLY: ELIZABETH STREB vs. GRAVITY (Catherine Gund, 2014)

Film Society of Lincoln Center, Walter Reade Theater

165 West 65th St. between Eighth Ave. & Broadway

Sunday, February 1, 3:20

Festival runs January 30 – February 3

212-875-5050

www.filmlinc.com

www.borntoflymovie.com

Over the last several years, New Yorkers have gotten the chance to see Elizabeth Streb’s Extreme Action Company perform such dazzling works as Ascension at Gansevoort Plaza, Kiss the Air! at the Park Avenue Armory, and Human Fountain at World Financial Center Plaza as her team of gymnast-dancer-acrobats risk their physical well-being in daring feats of strength, stamina, durability, and grace. In addition, Streb herself walked down the outside wall of the Whitney as part of a tribute to one of her mentors, Trisha Brown. Now Catherine Gund takes viewers behind the scenes in the exhilarating documentary Born to Fly: Elizabeth Streb vs. Gravity, going deep into the mind of the endlessly inventive and adventurous extreme action architect and the courage and fearlessness of her company. Gund follows Streb as she discusses her childhood, her dance studies, the formation of STREB in 1985, and her carefully thought out views on space, line, and movement as her work stretches the limits of what the human body can do. “I think my original belief and desire is to see a human being fly,” Streb says near the beginning of the film, which includes archival footage of early performances, family photos, and a warm scene in which the Rochester-born Streb and her partner, Laura Flanders, host a dinner party in their apartment, cooking for Bill T. Jones, Bjorn Amelan, Anne Bogart, Catharine Stimpson, and A. M. Homes. Gund also speaks with current and past members of the talented, ever-enthusiastic company — associate artistic director Fabio Tavares, Sarah Callan, Jackie Carlson, Leonardo Giron, Felix Hess, Samantha Jakus, Cassandre Joseph, John Kasten, and Daniel Rysak — who talk about their dedication to Streb’s vision while using such words as “challenge,” “velocity,” “endurance,” “magic,” “invincibility,” and “risk” to describe what they do and how they feel about it.

Over the last several years, New Yorkers have gotten the chance to see Elizabeth Streb’s Extreme Action Company perform such dazzling works as Ascension at Gansevoort Plaza, Kiss the Air! at the Park Avenue Armory, and Human Fountain at World Financial Center Plaza as her team of gymnast-dancer-acrobats risk their physical well-being in daring feats of strength, stamina, durability, and grace. In addition, Streb herself walked down the outside wall of the Whitney as part of a tribute to one of her mentors, Trisha Brown. Now Catherine Gund takes viewers behind the scenes in the exhilarating documentary Born to Fly: Elizabeth Streb vs. Gravity, going deep into the mind of the endlessly inventive and adventurous extreme action architect and the courage and fearlessness of her company. Gund follows Streb as she discusses her childhood, her dance studies, the formation of STREB in 1985, and her carefully thought out views on space, line, and movement as her work stretches the limits of what the human body can do. “I think my original belief and desire is to see a human being fly,” Streb says near the beginning of the film, which includes archival footage of early performances, family photos, and a warm scene in which the Rochester-born Streb and her partner, Laura Flanders, host a dinner party in their apartment, cooking for Bill T. Jones, Bjorn Amelan, Anne Bogart, Catharine Stimpson, and A. M. Homes. Gund also speaks with current and past members of the talented, ever-enthusiastic company — associate artistic director Fabio Tavares, Sarah Callan, Jackie Carlson, Leonardo Giron, Felix Hess, Samantha Jakus, Cassandre Joseph, John Kasten, and Daniel Rysak — who talk about their dedication to Streb’s vision while using such words as “challenge,” “velocity,” “endurance,” “magic,” “invincibility,” and “risk” to describe what they do and how they feel about it.

Elizabeth Streb and her partner, Laura Flanders, prepare for a dinner party in new documentary

Gund focuses on the latter, as virtually every one of Streb’s pieces is fraught with the possibility of serious injury, as evidenced by their titles alone: Fly, Impact, Rebound, Breakthru, and Ricochet, not to mention the use of such materials as spinning I-beams, plastic barricades, dangling harnesses, and a rotating metal ladder. “I have to be able to ask someone to do that and be okay about it. Those aren’t easy requests,” Streb explains. “Knowing where you are is how you survive the work,” adds former STREB dancer Hope Clark. Gund goes with Streb to her doctor, where the choreographer describes what happened to her gnarled feet, and also meets with former dancer DeeAnn Nelson Burton, who had to retire after breaking her back. The film concludes with an inside look at STREB’s spectacular “One Extraordinary Day,” a series of hair-raising site-specific events staged for the 2012 London Olympics at such locations as the Millennium Bridge, the London Eye, and the sphere-shaped city hall, photographed by documentary legend Albert Maysles. In her Kickstarter campaign, Gund (Motherland Afghanistan, A Touch of Greatness) said, “Action architect Elizabeth Streb has reinvented the language of movement. [Born to Fly] will rewrite the language of documentary.” That’s a bold declaration, but the film does have a lot of the same spirit that Streb displays in her awe-inspiring work. Born to Fly is screening with Benjamin Epps’s 2014 short, Angsters, on February 1 at 3:20 at the Walter Reade Theater as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s annual “Dance on Camera” series and will be followed by a Q&A with Gund and Streb. The festival runs January 30 – February 3 and includes such other movement-related works as Meredith Monk’s Girlchild Diary, followed by a Q&A with Monk and cast member Lanny Harrison; Kenneth Elvebakk’s Ballet Boys, set at the Norwegian Ballet School; Louis Wallecan’s Dancing Is Living: Benjamin Millepied, followed by a Q&A with the director; the U.S. premiere of Don Kent and Christian Dumais-Lvowski’s Jiri Kylian: Forgotten Memories; Isaki Lacuesta’s Perpetual Motion: The History of Dance in Catalonia, followed by a Q&A with choreographer Cesc Gelabert; and a handful of free events as well.

After working on two previous fashion-related films, Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel and Valentino: The Last Emperor, Frédéric Tcheng makes his solo directorial debut with Dior and I. In April 2012, fashion designer Raf Simons was named the new creative director of Christian Dior, bringing along his right-hand man, Pieter Mulier. Tcheng goes behind the scenes to follow Simons as he prepares his first-ever haute couture collection, which is due in a mere two months. Tcheng zooms in on the Belgian designer’s working methods and general anxiety as he takes over at the legendary company, developing important relationships with Dior CEO Sidney Toledano, première atelier flou Florence Chehet, première atelier tailleur Monique Bailly, the seamstresses, the models, and other employees. Simons chooses to pay homage to Dior’s past with his new collection while attempting to rid himself of the designation of “minimalist designer.” One of his most fascinating directions is attempting to incorporate the work of artist Sterling Ruby into his designs. All the while he is haunted by the ghost of company founder and New Look creator Christian Dior, who is shown by Tcheng in archival footage accompanied by a voice-over of Omar Berrada reading from Dior’s memoirs. Dior and I is a slight but affecting race against time, as one man in the present honors the past while laying the groundwork for a bright future. Dior and I opens April 10 at Film Forum and the Film Society of Lincoln Center, with Tcheng and Berrada appearing at Film Forum for the 7:30 show April 10 and the 5:20 show April 11; Tcheng will also be at the Walter Reade Theater for a Q&A following the 7:00 show April 11.

After working on two previous fashion-related films, Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel and Valentino: The Last Emperor, Frédéric Tcheng makes his solo directorial debut with Dior and I. In April 2012, fashion designer Raf Simons was named the new creative director of Christian Dior, bringing along his right-hand man, Pieter Mulier. Tcheng goes behind the scenes to follow Simons as he prepares his first-ever haute couture collection, which is due in a mere two months. Tcheng zooms in on the Belgian designer’s working methods and general anxiety as he takes over at the legendary company, developing important relationships with Dior CEO Sidney Toledano, première atelier flou Florence Chehet, première atelier tailleur Monique Bailly, the seamstresses, the models, and other employees. Simons chooses to pay homage to Dior’s past with his new collection while attempting to rid himself of the designation of “minimalist designer.” One of his most fascinating directions is attempting to incorporate the work of artist Sterling Ruby into his designs. All the while he is haunted by the ghost of company founder and New Look creator Christian Dior, who is shown by Tcheng in archival footage accompanied by a voice-over of Omar Berrada reading from Dior’s memoirs. Dior and I is a slight but affecting race against time, as one man in the present honors the past while laying the groundwork for a bright future. Dior and I opens April 10 at Film Forum and the Film Society of Lincoln Center, with Tcheng and Berrada appearing at Film Forum for the 7:30 show April 10 and the 5:20 show April 11; Tcheng will also be at the Walter Reade Theater for a Q&A following the 7:00 show April 11.

Over the last several years, New Yorkers have gotten the chance to see Elizabeth Streb’s Extreme Action Company perform such dazzling works as

Over the last several years, New Yorkers have gotten the chance to see Elizabeth Streb’s Extreme Action Company perform such dazzling works as

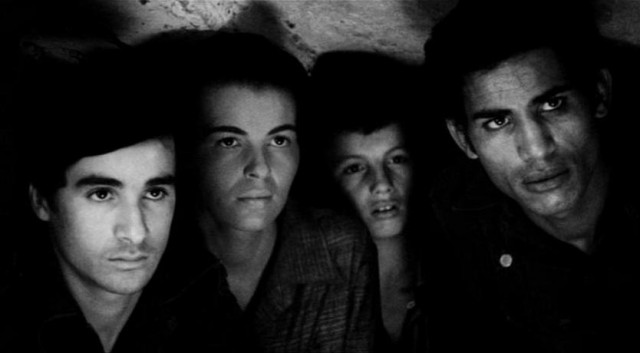

In Italian director Gillo Pontecorvo’s gripping neo-Realist war thriller The Battle of Algiers, a reporter asks French paratroop commander Lt. Col. Mathieu (Jean Martin), who has been sent to the Casbah to derail the Algerian insurgency, about an article Jean-Paul Sartre had just written for a Paris paper. “Why are the Sartres always born on the other side?” Mathieu says. “Then you like Sartre?” the reporter responds. “No, but I like him even less as a foe,” Mathieu coolly answers. In 1961, French existentialist Sartre wrote in the

In Italian director Gillo Pontecorvo’s gripping neo-Realist war thriller The Battle of Algiers, a reporter asks French paratroop commander Lt. Col. Mathieu (Jean Martin), who has been sent to the Casbah to derail the Algerian insurgency, about an article Jean-Paul Sartre had just written for a Paris paper. “Why are the Sartres always born on the other side?” Mathieu says. “Then you like Sartre?” the reporter responds. “No, but I like him even less as a foe,” Mathieu coolly answers. In 1961, French existentialist Sartre wrote in the