AFTERWARDSNESS

Park Ave. Armory

643 Park Ave. at Sixty-Seventh St.

May 19-26, $45 (limited tickets go on sale April 1)

www.armoryonpark.org

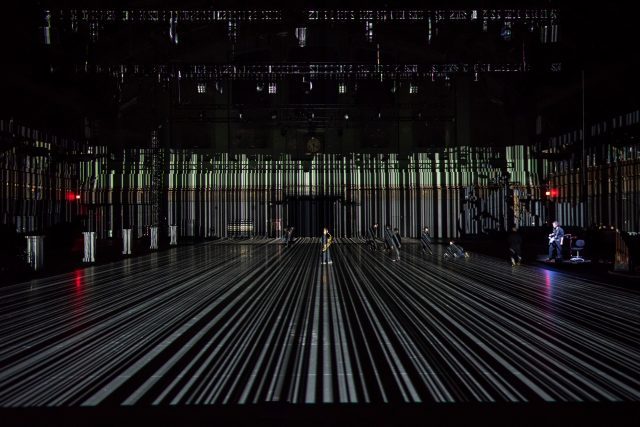

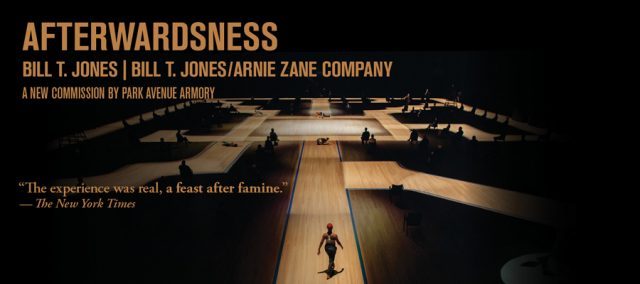

I’ve been tentative about the return of live, indoor music, dance, and theater, wondering how comfortable I would feel in an enclosed area with other audience members and onstage performers. Many of my colleagues who cover the arts are steadfastly against going to shows right now as things open up, while others have been having a ball going to the movies and eating inside. But when I received my invitation to see Afterwardsness at the Park Avenue Armory on March 24, I surprised myself with how much immediate glee I felt, how instantly exhilarated I was to finally, at last, see a show, in the same space with actual human beings. But my excitement was broken when it was announced that several members of the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company had tested positive for Covid-19 and the show, which had sold out quickly, had to be postponed. But now it’s back as part of the Armory’s Social Distance Hall season, running May 19 to 26; original ticket holders will get first dibs, with remaining tickets going on sale to the general public April 1. “Creating new, body-based work at a time when physical proximity is discouraged is no small feat,” Jones said in a statement. “However, as is often the case when artists are forced to push through limitations, this is when things get really good. Having the drill hall, this grand and glorious space to create and dance in, was quite liberating. The armory is a space like no other in New York City—and if it’s like no other in New York City, then it’s pretty unique in the world.”

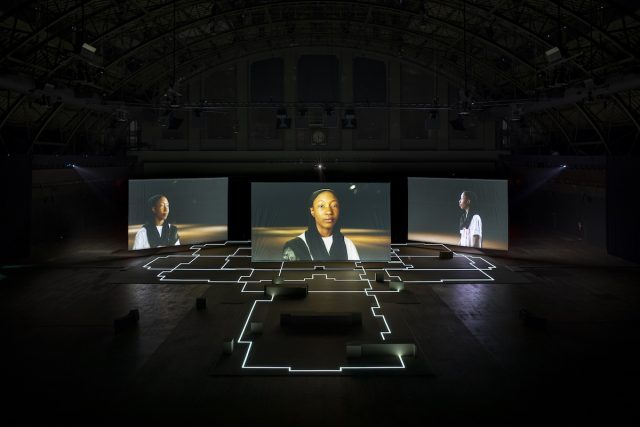

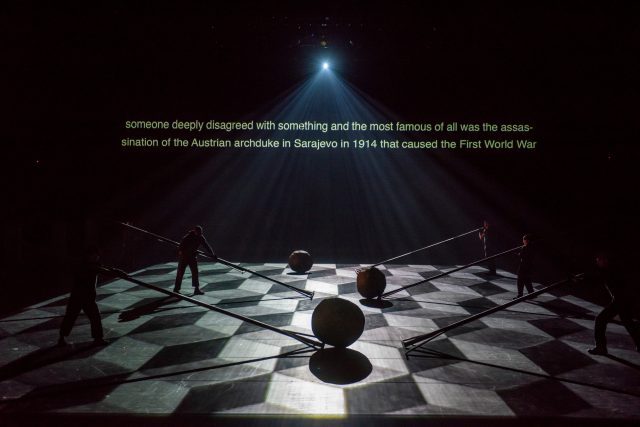

The sixty-five minute show, named for Freud’s concept of “a mode of belated understanding or retroactive attribution of sexual or traumatic meaning to earlier events,” will take place in the fifty-five-thousand-square-foot Wade Thompson Drill Hall, where one hundred audience members will be seated in chairs nine to twelve feet apart in all directions as the action unfolds around them. The hall has been updated with air-refreshing methods that exceed CDC and ASHRAE standards; there will be onsite testing and strict masking and social distancing policies. The work explores the isolation felt during the pandemic as well as the impact of the George Floyd protests and BLM movement. The choreography is by Tony winner Jones, with a new vocal composition by Holland Andrews, whose Museum of Calm recently streamed through the Baryshnikov Arts Center. Musical director Pauline Kim Harris will perform the violin solo “8:46” in tribute to Floyd, and there will also be new compositions by company members Vinson Fraley Jr. and Chanel Howard as well as excerpts from Olivier Messaien’s 1941 chamber piece Quartet for the End of Time, written while he was a POW in a German prison. The lighting is by Brian H. Scott, with sound by Mark Grey. The inaugural program at the armory is now Social! The Social Distance Dance Club, a collaboration between Steven Hoggett, Christine Jones, and David Byrne that runs April 9-22 and gives each audience member their own spotlight in which to move to choreography by Yasmine Lee.