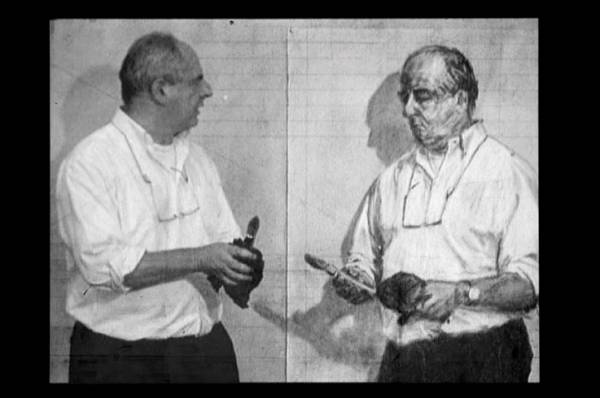

William Kentridge, from “7 Fragments for Georges Méliès,” 35mm and 16 mm animated film transferred to video, 2003 (courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery)

Museum of Modern Art

West 54th St. between Fifth & Sixth Aves.

Through May 17 (closed Tuesdays; Fridays free from 4:00 to 8:00)

Admission: $20 (includes same-day film screening)

212-708-9400

www.moma.org

In 2001, William Kentridge burst onto the New York art scene with an awe-inspiring show at the New Museum of Contemporary Art in SoHo, introducing to many the unique style employed by this South African artist who creates remarkable films made from charcoal drawings. Nearly ten years later, Kentridge is back with a bang, as multiple exhibits and special events have displayed the breadth of his work and his ingenuity, from his production of Shostakovich’s THE NOSE at the Met and his book of watermarks at Dieu Donné to screenings of his films with live music at the World Financial Center to a quartet of his “Drawings for Projection” series opening at the Jewish Museum on May 2. The centerpiece is the sensational display at MoMA, which continues through May 17. Arranged in a beautifully “generous layout,” as curator Klaus Biesenbach noted at the opening, “William Kentridge: Five Themes” features a bevy of rooms dedicated to the many worlds the artist has created via drawing, film, and a pair of model theaters. Kentridge himself is evident in much of his work, either as a character in his films or through the smudges, erasures, and new markings visible in his animation as he moves from page to page, revealing his unique and fascinating methods, laying himself—Jewish, white, a descendant of a well-known legal family in Johannesburg—bare. “The studio is an enclosed space, not just physically but also psychically, like an enlarged head; the pacing in the studio is the equivalent of ideas spinning around in one’s head, as if the brain is a muscle and can be exercised into fitness, into clarity,” he writes in the exhibition catalog, to which he has contributed several essays alongside a major examination by Mark Rosenthal, who organized the show at its first stop, SFMoMA.

William Kentridge, “Untitled (Man with Megaphone),” “Man with Megaphone Cluster,” etching, aquatint, drypoint, and engraving with roulette and crayon additions, 1998, and “Drawing for the film ‘Stereoscope,’” charcoal and pastel on paper, 1998-99 (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

At the heart of Kentridge’s oeuvre is his series of films depicting wealthy industrialist Soho Eckstein, naked dreamer Felix Teitlebaum, and the woman caught in between, Mrs. Eckstein. In such short films as “Stereoscope,” “Monument,” “History of the Main Complaint,” and “Mine,” all made without a script or a storyboard, Kentridge relates their continuing tale in an abstract narrative bursting with emotion, incorporating greed and loneliness, love and loss, and the division of the self. (It is not a coincidence that both Soho and Felix resemble the artist himself.) But “Thick Time: Soho and Felix” is only one of the themes that runs through the exhibit. “Ubu and the Procession” includes two films that harken back to Alfred Jarry’s Ubu character, reimagining him in South Africa; “The Magic Flute” and “The Nose” take visitors behind the scenes of Kentridge’s recent productions of the two operas, the first held at BAM in 2007, the latter at the Met in March. “Artist in the Studio” consists of “7 Fragments for Georges Méliès,” seven films on view together in one room, all of which reveal the artist at work. The excellent catalog contains a must-have DVD that goes even further into Kentridge’s process, presenting discarded snippets, fascinating revelations about his method, and complete versions of his first experimental short as well as the full-length “Tide Table.” “I believe that in the indeterminacy of drawing—the contingent way that images arrive in the work—lies some kind of model of how we live our lives,” Kentridge has said. “The activity of drawing is a way of trying to understand who we are and how we operate in the world.” This exciting survey at MoMA is all that and more.