Film Forum

209 West Houston St.

Friday, August 19, through Tuesday, September 13, $14

212-727-8110

filmforum.org

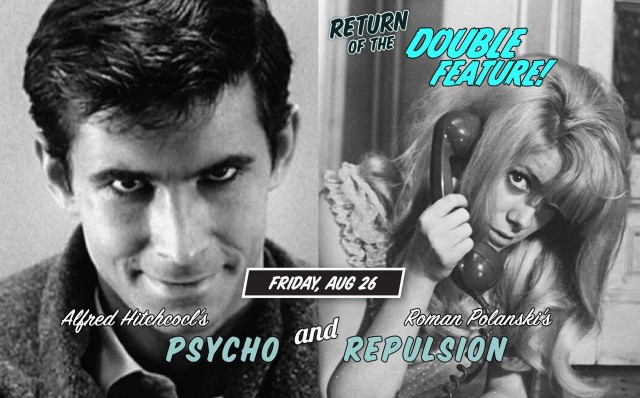

Once upon a time, in a land far, far away, you could pay one single admission and see two professional baseball games, called a double header. “Let’s play two!” Mr. Cub, Ernie Banks, famously said in July 1969. And you could stay and watch both games for one regular price, without having to clear out after the first contest. Also in that magical land of long ago, you see two movies for the price of one, known as a double feature. As Richard O’Brien sings in The Rocky Horror Picture Show, “I wanna go — oh oh oh oh / to the late night, double feature, picture show.” Film Forum, which often hosts double features, is now honoring the two-pack with “Return of the Double Feature,” twenty-six pairings of fifty-two classic movies, brought together by director, star, theme, writer, or other reason. Master programmer Bruce Goldstein gets things going with the Alfred Hitchcock / Jimmy Stewart duo of Vertigo and Rear Window, followed by Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt and Breathless, Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory and The Killing, and F. W. Murnau’s Sunrise and Nosferatu. After that, the double bills become more conceptual, such as Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo with Sergio Corbucci’s Django, Nicholas Ray’s In a Lonely Place with Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat, and, perhaps best of all, Hitchcock’s Psycho with Roman Polanski’s Repulsion.

You can catch Ruth Gordon in Harold and Maude and Where’s Poppa?, Orson Welles in Carol Reed’s The Third Man and his own The Lady from Shanghai, and Gene Tierney in Otto Preminger’s Laura and John Stahl’s Leave Her to Heaven. There are double features by Robert Altman, Charlie Chaplin, Terrence Malick, Alain Resnais, and Luis Buñuel; based on novels by James M. Cain and Raymond Chandler; and starring Marlon Brando, Humphrey Bogart, Toshiro Mifune, and Cary Grant. Among the other dynamic duos are Vittorio De Sica’s The Bicycle Thief with Tim Burton’s Pee Wee’s Big Adventure, Burton’s Ed Wood with Wood’s Plan 9 from Outer Space, and Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder with André de Toth’s House of Wax, both shown in 3-D. Instead of bingeing on Netflix, you might as well just settle in for the long haul at Film Forum and take in as much of this superb master class in cinema as you can, presented two flicks at a time, just like in the good old days.

Akira Kurosawa’s thrilling police procedural, Stray Dog, is one of the all-time-great film noirs. When newbie detective Murakami (Toshirō Mifune) gets his Colt lifted on a trolley, he fears he’ll be fired if he does not get it back. But as he searches for the weapon, he discovers that it is being used in a series of robberies and murders — for which he feels responsible. Teamed with seasoned veteran Sato (Takashi Shimura), Murakami risks his career — and his life — as he tries desperately to track down his gun before it is used again. Kurosawa makes audiences sweat, showing postwar Japan in the midst of a brutal heat wave, with Murakami, Sato, dancer Harumi Namiki (Keiko Awaji), and others constantly mopping their brows — the heat is so palpable, you can practically see it dripping off the screen. (You’ll find yourself feeling relieved when Sato hits a button on a desk fan, causing it to turn toward his face.) In his third of sixteen films made with Kurosawa, Mifune plays Murakami with a stalwart vulnerability, working beautifully with Shimura’s cool, calm cop who has seen it all and knows how to handle just about every situation. (Shimura was another Kurosawa favorite, appearing in twenty-one of his films.)

Akira Kurosawa’s thrilling police procedural, Stray Dog, is one of the all-time-great film noirs. When newbie detective Murakami (Toshirō Mifune) gets his Colt lifted on a trolley, he fears he’ll be fired if he does not get it back. But as he searches for the weapon, he discovers that it is being used in a series of robberies and murders — for which he feels responsible. Teamed with seasoned veteran Sato (Takashi Shimura), Murakami risks his career — and his life — as he tries desperately to track down his gun before it is used again. Kurosawa makes audiences sweat, showing postwar Japan in the midst of a brutal heat wave, with Murakami, Sato, dancer Harumi Namiki (Keiko Awaji), and others constantly mopping their brows — the heat is so palpable, you can practically see it dripping off the screen. (You’ll find yourself feeling relieved when Sato hits a button on a desk fan, causing it to turn toward his face.) In his third of sixteen films made with Kurosawa, Mifune plays Murakami with a stalwart vulnerability, working beautifully with Shimura’s cool, calm cop who has seen it all and knows how to handle just about every situation. (Shimura was another Kurosawa favorite, appearing in twenty-one of his films.)

Japan Society’s Monthly Classics series continues February 5 with the story of one of the screen’s most brutal antiheroes, a samurai you can’t help but root for despite his coldhearted brutality, a heartless killer called “a man from hell.” Based on Kaizan Nakazato’s forty-one-volume serial novel Dai-bosatsu Tōge, Kihachi Okamoto’s The Sword of Doom, aka The Great Bodhisattva Pass, begins in 1860 with Ryunosuke Tsukue (Tatsuya Nakadai) slaying an elderly Buddhist pilgrim (Ko Nishimura) apparently for no reason as the man visits a far-off mountain grave. Shortly before Ryunosuke is to battle Bunnojo Utsuki (Ichiro Nakaya) in a competition using unsharpened wooden swords, the man’s wife, Ohama (Michiyo Aratama), comes to him, begging for Ryunosuke to lose the match on purpose to save her family’s future. A master swordsman with an unorthodox style, Ryunosuke takes advantage of the situation in more ways than one. As emotionless as he is fearless, Ryunosuke is soon ambushed on a forest road, but killing, to him, comes natural, whether facing one man or dozens — or even hundreds. The only person he shows even the slightest respect for is Toranosuke Shimada (Toshirō Mifune), the instructor at a sword-fighting school. “We have rules concerning strangers,” Toranosuke tells him, but Ryunosuke plays by no rules. “The sword is the soul. Study the soul to know the sword. Evil mind, evil sword,” Toranosuke adds, words that torment Ryunosuke, who tries to start a family in spite of his hard, detached demeanor. But regardless of circumstance, Ryunosuke continues on his bloody path, culminating in an unforgettable battle that is one of the finest of the jidaigeki genre.

Japan Society’s Monthly Classics series continues February 5 with the story of one of the screen’s most brutal antiheroes, a samurai you can’t help but root for despite his coldhearted brutality, a heartless killer called “a man from hell.” Based on Kaizan Nakazato’s forty-one-volume serial novel Dai-bosatsu Tōge, Kihachi Okamoto’s The Sword of Doom, aka The Great Bodhisattva Pass, begins in 1860 with Ryunosuke Tsukue (Tatsuya Nakadai) slaying an elderly Buddhist pilgrim (Ko Nishimura) apparently for no reason as the man visits a far-off mountain grave. Shortly before Ryunosuke is to battle Bunnojo Utsuki (Ichiro Nakaya) in a competition using unsharpened wooden swords, the man’s wife, Ohama (Michiyo Aratama), comes to him, begging for Ryunosuke to lose the match on purpose to save her family’s future. A master swordsman with an unorthodox style, Ryunosuke takes advantage of the situation in more ways than one. As emotionless as he is fearless, Ryunosuke is soon ambushed on a forest road, but killing, to him, comes natural, whether facing one man or dozens — or even hundreds. The only person he shows even the slightest respect for is Toranosuke Shimada (Toshirō Mifune), the instructor at a sword-fighting school. “We have rules concerning strangers,” Toranosuke tells him, but Ryunosuke plays by no rules. “The sword is the soul. Study the soul to know the sword. Evil mind, evil sword,” Toranosuke adds, words that torment Ryunosuke, who tries to start a family in spite of his hard, detached demeanor. But regardless of circumstance, Ryunosuke continues on his bloody path, culminating in an unforgettable battle that is one of the finest of the jidaigeki genre.

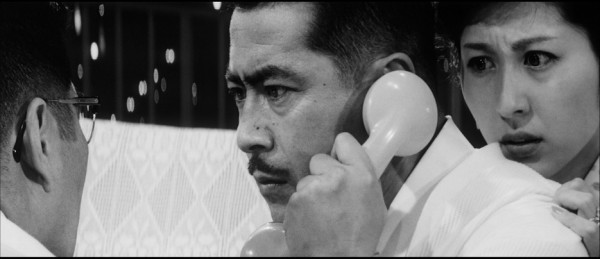

On the verge of being forced out of the company he has dedicated his life to, National Shoes executive Kingo Gondo’s (Toshirō Mifune) life is thrown into further disarray when kidnappers claim to have taken his son, Jun (Toshio Egi), and are demanding a huge ransom for his safe return. But when Gondo discovers that they have mistakenly grabbed Shinichi (Masahiko Shimazu), the son of his chauffeur, Aoki (Yutaka Sada), he at first refuses to pay. But at the insistence of his wife (Kyogo Kagawa), the begging of Aoki, and the advice of police inspector Taguchi (Kenjiro Ishiyama), he reconsiders his decision, setting in motion a riveting police procedural that is filled with tense emotion. Loosely based on Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct novel King’s Ransom, Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low, photographed by longtime Kurosawa cinematographer Asakazu Nakai, is divided into two primary sections: The first half takes place in Gondo’s luxury home, orchestrated like a stage play as the characters are developed and the plan takes hold. The second part of the film follows the police, under the leadership of Chief Detective Tokura (Tatsuya Nakadai), as they hit the streets of the seedier side of Yokohama in search of the kidnappers. Known in Japan as Tengoku to Jigoku, which translates as Heaven and Hell, High and Low is an expert noir, a subtle masterpiece that tackles numerous socioeconomic and cultural issues as Gondo weighs the fate of his business against the fate of a small child; it all manages to feel as fresh and relevant today as it probably did back in the ’60s.

On the verge of being forced out of the company he has dedicated his life to, National Shoes executive Kingo Gondo’s (Toshirō Mifune) life is thrown into further disarray when kidnappers claim to have taken his son, Jun (Toshio Egi), and are demanding a huge ransom for his safe return. But when Gondo discovers that they have mistakenly grabbed Shinichi (Masahiko Shimazu), the son of his chauffeur, Aoki (Yutaka Sada), he at first refuses to pay. But at the insistence of his wife (Kyogo Kagawa), the begging of Aoki, and the advice of police inspector Taguchi (Kenjiro Ishiyama), he reconsiders his decision, setting in motion a riveting police procedural that is filled with tense emotion. Loosely based on Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct novel King’s Ransom, Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low, photographed by longtime Kurosawa cinematographer Asakazu Nakai, is divided into two primary sections: The first half takes place in Gondo’s luxury home, orchestrated like a stage play as the characters are developed and the plan takes hold. The second part of the film follows the police, under the leadership of Chief Detective Tokura (Tatsuya Nakadai), as they hit the streets of the seedier side of Yokohama in search of the kidnappers. Known in Japan as Tengoku to Jigoku, which translates as Heaven and Hell, High and Low is an expert noir, a subtle masterpiece that tackles numerous socioeconomic and cultural issues as Gondo weighs the fate of his business against the fate of a small child; it all manages to feel as fresh and relevant today as it probably did back in the ’60s.

We used to think that Aki Kaurismäki’s

We used to think that Aki Kaurismäki’s