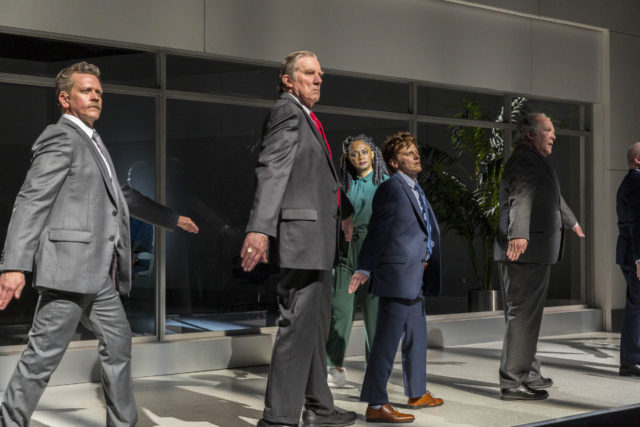

Daniel Craig and Ruth Negga star as a devious husband and wife in Sam Gold’s unusual take on the Scottish play at the Longacre (photo by Joan Marcus)

MACBETH

Longacre Theatre

220 West 48th St. between Broadway & Eighth Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through July 10, $35-$425

macbethbroadway.com

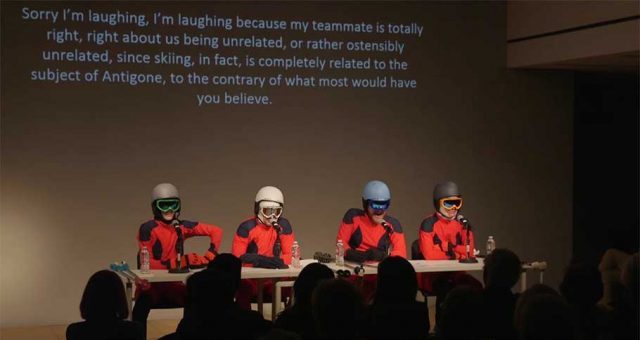

As you enter the Longacre Theatre to see the latest conjuring of Macbeth, the thane’s first appearance on the Great White Way since Terry Hands’s 2000 version with Kelsey Grammer lasted just thirteen performances, the sparse stage is a scene of activity. On one side, three people are cooking soup while listening to a podcast. Various others wander about or are busy in the wings. Front and center, the ghost light glows — a superstition that is believed to keep at bay supernatural beings who haunt theaters and can curse shows, although it usually is turned on only after everyone has left and the venue is empty. During the pandemic lockdown, many theaters kept their ghost lights on in the hope of eventually returning. Thus, once inside the Longacre, you feel as if you’ve walked into some kind of rehearsal that is getting ready to close up for the night.

More than any other of his major works, Shakespeare’s 1606 tragedy invites experimentation of a high order. In the past fifteen years, I’ve seen no fewer than ten adaptations of the Scottish play, including an all-women version that took place at a contemporary girls school, a re-creation of Orson Welles’s radio production, a presentation that required the audience to make its way through a dark heath to get to their seats, one set during the cold war and prominently featuring a bevy of video projections, another occurring inside the head of an institutionalized man, and a mashup with a Japanese manga that moved the action to a blue boxing ring.

Like King Lear, it also attracts big-name star power; among those who have portrayed the thane of Cawdor in New York since 2006 are Sir Patrick Stewart, Ethan Hawke, Sir Kenneth Branagh, Alan Cumming, Liev Schreiber, and Corey Stoll. Now comes James Bond himself, Daniel Craig, in a production helmed by Tony and Obie winner Sam Gold, who is responsible for the much-derided 2019 Broadway revival of Lear with Glenda Jackson in the title role.

Macbeth (Daniel Craig) speaks with a pair of murderers (Danny Wolohan and Michael Patrick Thornton) in Shakespeare adaptation (photo by Joan Marcus)

While the trio, who turn out to be the three witches (portrayed alternately by Phillip James Brannon, Bobbi MacKenzie, Maria Dizzia, Che Ayende, Eboni Flowers, and Peter Smith), continue stirring the pot, Michael Patrick Thornton, who plays the nobleman Lennox, wheels onto the stage and provides a curtain speech about James I’s obsession with witches in the seventeenth century while also asking the audience to, all at once, shout out the name of the show, which is supposed to bring bad luck when spoken inside a theater. Very few people joined in.

Gold has pared down the production to the point where no single actor is the star; there’s an equality among the diverse cast that does not force us to swoon at either Craig or Oscar, Emmy, and Olivier nominee Ruth Negga as Lady Macbeth and instead allows the audience to appreciate the other participants. The text is delivered without many flourishes, as famous lines come and go at a regular pace, with some favorites getting cut; for example, the witches never say, “Double, double toil and trouble.” The actors are dressed in Suttirat Larlarb’s contemporary costumes; Macbeth’s succession from military jacket to paisley bathrobe to fluffy white fur coat is a hoot.

Christine Jones’s set is the antithesis of royalty; the “thrones” are two old, ratty chairs, and the banquet table lacks fancy dinnerware. The crown worn by King Duncan (Paul Lazar) is just plain silly, like a high school prop, but even funnier is when Lazar, following the monarch’s murder, removes his fat suit in front of us and proceeds to play other characters. There is much doubling and tripling of actors, so it’s not always clear who’s who. Amber Gray excels as Banquo and her ghost but is seen later as a gentlewoman. Danny Wolohan is Seyton, a lord, a murderer, and a bloody captain who has lost part of one leg. Emeka Guindo is both Fleance and young Siward. Downtown legend Lazar also shows up as old Siward and the porter, who, in front of the curtain, discusses with Macduff (Grantham Coleman, though I saw understudy Ayende) and Lennox how drink affects sexual prowess. To further the comparison, Macbeth later pops open a can of light beer.

Jeremy Chernick’s special effects feature lots of blood, some of which is added to the simmering soup (along with innards). As Macbeth warns, “Blood will have blood.”

Three witches (Phillip James Brannon, Bobbi MacKenzie, Maria Dizzia) stir up a cauldron of trouble in Macbeth (photo by Joan Marcus)

So what’s it all about? Though uneven, Gold’s adaptation subverts our expectations about stardom, Broadway, and Shakespeare. It’s hard to believe that this is the same story told with such fierce elegance by Joel Coen in his 2021 Oscar-nominated film, The Tragedy of Macbeth, with a dominating Denzel Washington as Macbeth and a haunting Frances McDormand as his devious partner. In fact, under Gold’s supervision, the real standout is Thornton, who relates to the audience with a sweet warmth and playful sense of humor. However, as Macbeth also says, “And nothing is, but what is not.”

Gold (Fun Home; A Doll’s House, Part 2) previously directed Craig (Betrayal, A Steady Rain) as Iago in an intimate and compelling Othello at New York Theatre Workshop and Oscar Isaac in Hamlet at the Public; Negga has played Ophelia at London’s National Theatre and Hamlet at St. Ann’s Warehouse. The ads for Macbeth might push the star draw of this new production, but that is not what Gold is focusing on.

He may not be making any grand statements about lust, greed, and power, but he is investigating the common foibles of humanity, the desires we all have and our considerations of how far we will go to achieve them. Is he completely successful? No, but that doesn’t mean he hasn’t given us an intriguing, provocative, unconventional, absurdly comic, and, yes, highly entertaining production of one of the greatest tragedies ever written.

As Lady Macbeth advises, “What’s done, cannot be undone.”

Peter Sarsgaard gives a beautifully gentle performance as a house tuner in Michael Tyburski’s feature debut, The Sound of Silence. Sarsgaard is Peter Lucian, an idiosyncratic New Yorker who is hired by people to investigate how sounds in their homes might be affecting them in negative ways, impacting their sleeping habits, success at work, and overall mood. Walking from room to room with tuning forks and a tape recorder, Peter tracks seemingly impossible-to-hear noise and suggests alterations that will change his clients’ lives, sometimes as simple as replacing a small appliance. He is also mapping the city itself, documenting buildings and street corners by the musical notes they emit. At the urging of his mentor, Robert Feinway (Austin Pendleton), he hires Samuel Diaz (Tony Revolori) to assist him as he prepares to publish his findings, something he prefers to do alone. Meanwhile, CEO Harold Carlyle (Bruce Altman) wants Peter to join his firm and turn his unique skill into a big-time money-making venture, but Peter has no interest in corrupting his unusual profession. When he hits a snag trying to solve the problems of his latest client, Ellen Chasen (Rashida Jones), he becomes obsessed, desperate to find the answer as his calm, even-keeled life suddenly becomes turbulent and disorderly.

Peter Sarsgaard gives a beautifully gentle performance as a house tuner in Michael Tyburski’s feature debut, The Sound of Silence. Sarsgaard is Peter Lucian, an idiosyncratic New Yorker who is hired by people to investigate how sounds in their homes might be affecting them in negative ways, impacting their sleeping habits, success at work, and overall mood. Walking from room to room with tuning forks and a tape recorder, Peter tracks seemingly impossible-to-hear noise and suggests alterations that will change his clients’ lives, sometimes as simple as replacing a small appliance. He is also mapping the city itself, documenting buildings and street corners by the musical notes they emit. At the urging of his mentor, Robert Feinway (Austin Pendleton), he hires Samuel Diaz (Tony Revolori) to assist him as he prepares to publish his findings, something he prefers to do alone. Meanwhile, CEO Harold Carlyle (Bruce Altman) wants Peter to join his firm and turn his unique skill into a big-time money-making venture, but Peter has no interest in corrupting his unusual profession. When he hits a snag trying to solve the problems of his latest client, Ellen Chasen (Rashida Jones), he becomes obsessed, desperate to find the answer as his calm, even-keeled life suddenly becomes turbulent and disorderly.