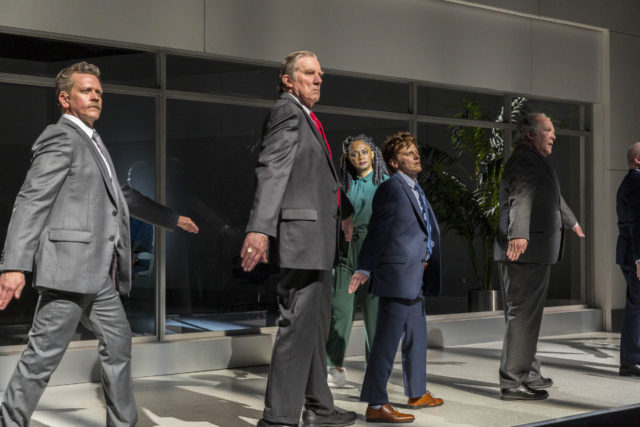

Maxwell Alexandre’s “Pardo é Papel: The Glorious Victory and New Power” reimagines the museum/gallery experience (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

PARDO È PAPEL: THE GLORIOUS VICTORY AND NEW POWER

The Shed, the Bloomberg Building at Hudson Yards

545 West 30th St. at Eleventh Ave.

Wednesday – Sunday through January 8, $10

theshed.org

online slideshow

As you enter Brazilian artist Maxwell Alexandre’s debut North American solo exhibition at the Shed, “Pardo é Papel: The Glorious Victory and New Power,” the key work is to your immediate right, a large, vertical empty gold frame on wrinkled brown kraft paper hanging from the ceiling on plastic wires, its borders populated by cartoonish characters. What’s critical is what’s not in the frame: a person, particularly a Black one. It is also infused with an engaging yet disturbing fragility, as if it could fall apart at any minute.

The Shed’s level four gallery is divided into two sections, “The Glorious Victory” and “New Power,” two series that make up Alexandre’s “Pardo é Papel,” which translates as “brown is paper”; the term refers not only to the pardo paper Alexandre uses but the Brazilian census category that forces citizens to choose between Black, brown (mixed race), or white, identifying themselves by skin color and not culture and ancestry and contributing to the whitening of the country since fewer people will call themselves Black. The exhibition, organized by curator at large Alessandra Gómez, is arranged as mazes filled with images that celebrate Black empowerment and foster the idea of community amid rampant consumerism and discrimination.

“When I started painting on brown paper, it was not only a conceptual issue but a political and social issue as well,” Alexandre explains in a promotional video. “And some years later, I had an idea of painting a self-portrait, much for the sake of wanting to represent a character that was Black and blond, with dyed hair. . . . ‘Pardo é Papel’ is a series that talks specifically about empowerment, self-esteem, and the speculation of the future of glory and prosperity for Black people. So it starts pointing to these various directions, and these paintings for me are very representative because they speak of this moment of ascension, of my ascension as an artist. That I have my integrity as a Black Brazilian favelado, and as an individual, as an artist.”

The works feature pop-culture references scattered throughout, from such recording artists as Baco Exu do Blues, Djonga, BK, and Nina Simone to such consumer goods as the chocolate drink Toddynho (with its smiling mascot), Danone yogurt, and Capri pools; the latter is the focus of one of the most powerful pieces in the show, Até Deus inveja o homem preto (Even God envies the Black man), which depicts a Black swimmer with blond hair at the upper left, sucking on a long red-and-white straw that goes into the butt of Toddynho at the lower right, an actual small pool of water on the floor at the corner of the painting.

Alexandre, who was born in Rio de Janeiro in 1990 and was a professional street inline skater for twelve years, also incorporates shoe polish on many canvases, the same polish he used while serving in the army. The majority of the people in his works do not have full faces, adding to the confusion surrounding their identity. In the back room, a painting of velvet ropes is next to a long, vertical work in which four couples — and Brazilian soccer star Neymar — are looking around, as if at an art gallery, but above them is a gold landscape with no figures; at the far end, an older, perhaps wiser gentleman is walking away, ready for a different future. Meanwhile, access is blocked to a second door from the hallway, but we can see the back of a painting, in which a small, solitary Black person is floating in the upper right rectangle, facing the hall, not the gallery, as if being kept out, not allowed inside.

“Pardo é Papel” calls into question how we experience galleries and museums, from the figures depicted in the works to the creators, bringing to the forefront the history of the exclusion of artists of color; even the wall text is written on pardo paper. Discussing “New Power” in the accompanying pamphlet, Alexandre notes, “From a biographical perspective, the series talks about how I, upon arriving at a position of success, looked around and found myself in a world dominated almost exclusively by white people. The series is a study and mapping of the contradictions, pitfalls, and opportunities in this field so that more Black people can infiltrate it not only as spectators or subjects but also as agents in positions of power: curators, artists, collectors, directors, funders, gallerists, and so on.”

“Pardo é Papel” goes a long way to that necessary goal.