The film career of French artist Daniel Pommereulle is being celebrated at Metrograph this month

SIX MORAL TALES: LA COLLECTIONNEUSE (Eric Rohmer, 1967)

Metrograph

7 Ludlow St. between Canal & Hester Sts.

Saturday, September 14, 2:30

Sunday, September 15, 11:00 am

Series runs September 13-29

212-660-0312

metrograph.com

On September 12, the exhibit “Daniel Pommereulle: Premonition Objects” opens at Ramiken on Grand St. On September 13, Metrograph kicks off the two-week series “One More Time: The Cinema of Daniel Pommereulle,” consisting of seven programs featuring the French painter, sculptor, filmmaker, performer, and poet who died in 2003 at the age of sixty-six. First up is “Daniel Pommereulle X3,” bringing together Pommereulle’s shorts One More Time and Vite and Anton Bialas and Ferdinand Gouzon’s 2021 Monuments aux vivants, which documents the artist’s sculptural work; curators Boris Bergmann and Armance Léger will take part in a postscreening Q&A moderated by filmmaker Kathy Brew. “Pommereulle was one of those people who could stand firm against the all-consuming metropolis: someone who never compromised, who never sold his soul — even to America. We joyously return Pommereulle to New York: a necessary encounter, a poetic reward,” Léger and Bergmann said in a statement. The festival also includes Jean-Luc Godard’s Weekend, Jean Eustache’s The Mother and the Whore, Marc’O’s Les Idoles, Jackie Raynal’s Deux Fois, serge Bard and Olivier Mosset’s Ici et maintenant and Fun and Games for Everyone, and Eric Rohmer’s La Collectionneuse.

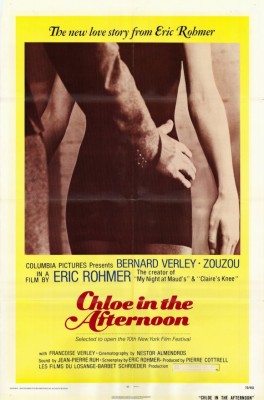

“Razor blades are words,” art critic Alain Jouffroy tells painter Daniel Pommereulle (Daniel Pommereulle) in one of the prologues at the start of La Collectionneuse, the fourth film in French master Eric Rohmer’s Six Moral Tales (falling between My Night at Maud’s and Claire’s Knee). Words might have the ability to cut, but they don’t seem to have much impact on the three people at the center of the film, which offers a sort of alternate take on François Truffaut’s Jules et Jim. Needing a break from his supposedly strenuous life, gallerist Adrien (Patrick Bauchau, who also appeared in La Carrière de Suzanne, Rohmer’s second morality tale) decides to vacation at the isolated St. Tropez summer home of the never-seen Rodolphe. Daniel is also at the house, along with Haydée (Haydée Politoff), a beautiful young woman who spends much of the film in a bikini and being taken out by a different guy nearly every night. Adrien decides that she is a “collector” of men, and the three needle one another as they discuss life and love, sex and morality, beauty and ugliness. Adrien might claim to want to have nothing to do with Haydée, but he keeps spending more and more time with her, even though he never stops criticizing her lifestyle. He even uses her as a pawn when trying to get an art collector named Sam (played by former New York Times film critic Eugene Archer under the pseudonym Seymour Hertzberg) to invest in his gallery.

While everybody else in the film pretty much knows what they want, Adrien, who purports to understand life better than all of them, is a sad, lost soul, unable to get past his high-and-mighty attitude. Rohmer crafted the roles of Daniel and Haydée specifically for Pommereulle and Politoff, who improvised much of their dialogue; Bauchau opted not to take that route, making for a fascinating relationship among the three very different people. La Collectionneuse is beautifully shot in 35mm by Néstor Almendros, the bright colors of the characters’ clothing mixing splendidly with the countryside and ocean while offering a striking visual counterpoint to the constant ennui dripping off the screen. His camera especially loves Politoff, regularly exploring her body inch by inch. The film is both Rohmer’s and Almendros’s first color feature; Almendros would go on to make more films with the director, as well as with Truffaut, even after coming to Hollywood and shooting such films as Days of Heaven, Kramer vs. Kramer, and Sophie’s Choice. Winner of a Silver Bear Extraordinary Jury Prize at the 1967 Berlinale, La Collectionneuse is screening September 14 and 15 at Metrograph.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]

Justifiably recognized as one of the most beautiful films ever made, writer-director Terrence Malick’s sophomore effort, Days of Heaven, is a visually breathtaking tale of love, desperation, and survival in WWI-era America. After accidentally killing his boss (Stuart Margolin) in a Chicago steel mill, Bill (Richard Gere) immediately flees to the Texas Panhandle with his girlfriend, Abby (Brooke Adams), and his much younger sister, Linda (Linda Manz). Because they are unmarried, Bill and Abby pretend to be brother and sister — evoking the biblical story of Abraham introducing his wife Sarah as his sibling — and get a job working in the wheat fields owned by a reserved, possibly ill farmer (Sam Shepard) who is instantly smitten with Abby. Soon a complex love triangle develops in which money, class, and power play a key role. As beautiful as the main characters are — Gere and Shepard particularly are shot in ways that emphasize their tender but rugged good looks — they are outshone by the gorgeous landscapes and sunsets photographed by Nestor Almendros (who won an Oscar for Best Cinematography) and Haskell Wexler, as well as Jack Fisk’s stunning art direction, all of which were directly inspired by

Justifiably recognized as one of the most beautiful films ever made, writer-director Terrence Malick’s sophomore effort, Days of Heaven, is a visually breathtaking tale of love, desperation, and survival in WWI-era America. After accidentally killing his boss (Stuart Margolin) in a Chicago steel mill, Bill (Richard Gere) immediately flees to the Texas Panhandle with his girlfriend, Abby (Brooke Adams), and his much younger sister, Linda (Linda Manz). Because they are unmarried, Bill and Abby pretend to be brother and sister — evoking the biblical story of Abraham introducing his wife Sarah as his sibling — and get a job working in the wheat fields owned by a reserved, possibly ill farmer (Sam Shepard) who is instantly smitten with Abby. Soon a complex love triangle develops in which money, class, and power play a key role. As beautiful as the main characters are — Gere and Shepard particularly are shot in ways that emphasize their tender but rugged good looks — they are outshone by the gorgeous landscapes and sunsets photographed by Nestor Almendros (who won an Oscar for Best Cinematography) and Haskell Wexler, as well as Jack Fisk’s stunning art direction, all of which were directly inspired by

Winner of both the Palme d’Or and the Critics Prize at the 1984 Cannes Film Festival, Wim Wenders’s Paris, Texas is a stirring and provocative road movie about the dissolution of the American family and the death of the American dream. Written by Sam Shepard and adapted by L. M. Kit Carson, the two-and-a-half-hour film opens with a haggard man (Harry Dean Stanton) wandering through a vast, deserted landscape. A close-up of him in his red hat, seen against blue skies and white clouds, evokes the American flag. (Later shots show him looking up at a flag flapping in the breeze, as well as a graffiti depiction of the Statue of Liberty.) After he collapses in a bar in the middle of nowhere, he is soon discovered to be Travis Henderson, a husband and father who has been missing for four years. His brother, Walt (Dean Stockwell), a successful L.A. billboard designer, comes to take him home, but Travis, remaining silent, keeps walking away. He eventually reveals that he is trying to get to Paris, Texas, where he has purchased a plot of land in the desert, but he avoids discussing his past and why he walked out on his wife, Jane (Nastassja Kinski), and son, Hunter (Hunter Carson, the son of L. M. Kit Carson and Karen Black), who is being raised by Walt and his wife, Anne (Aurore Clément). An odd man who is afraid of flying (a genuine fear of Shepard’s), has a penchant for arranging shoes, and falls asleep at key moments, Travis sets out with Hunter to find Jane and make something out of his lost life.

Winner of both the Palme d’Or and the Critics Prize at the 1984 Cannes Film Festival, Wim Wenders’s Paris, Texas is a stirring and provocative road movie about the dissolution of the American family and the death of the American dream. Written by Sam Shepard and adapted by L. M. Kit Carson, the two-and-a-half-hour film opens with a haggard man (Harry Dean Stanton) wandering through a vast, deserted landscape. A close-up of him in his red hat, seen against blue skies and white clouds, evokes the American flag. (Later shots show him looking up at a flag flapping in the breeze, as well as a graffiti depiction of the Statue of Liberty.) After he collapses in a bar in the middle of nowhere, he is soon discovered to be Travis Henderson, a husband and father who has been missing for four years. His brother, Walt (Dean Stockwell), a successful L.A. billboard designer, comes to take him home, but Travis, remaining silent, keeps walking away. He eventually reveals that he is trying to get to Paris, Texas, where he has purchased a plot of land in the desert, but he avoids discussing his past and why he walked out on his wife, Jane (Nastassja Kinski), and son, Hunter (Hunter Carson, the son of L. M. Kit Carson and Karen Black), who is being raised by Walt and his wife, Anne (Aurore Clément). An odd man who is afraid of flying (a genuine fear of Shepard’s), has a penchant for arranging shoes, and falls asleep at key moments, Travis sets out with Hunter to find Jane and make something out of his lost life.

Nominated for the Palme d’Or and a Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, My Night at Maud’s, Éric Rohmer’s fourth entry in his Six Moral Tales series (falling between La Collectionneuse and Claire’s Knee) continues the French director’s fascinating exploration of love, marriage, and tangled relationships. Three years removed from playing the romantic racecar driver Jean-Louis in Claude Lelouch’s A Man and a Woman, Jean-Louis Trintignant again stars as a man named Jean-Louis, this time a single thirty-four-year-old Michelin engineer living a relatively solitary life in the French suburb of Clermont. A devout Catholic, he is developing an obsession with a fellow churchgoer, the blonde, beautiful Françoise (Marie-Christine Barrault), about whom he knows practically nothing. After bumping into an old school friend, Vidal (Antoine Vitez), the two men delve into deep discussions of religion, Marxism, Pascal, mathematics, Jansenism, and women. Vidal then invites Jean-Louis to the home of his girlfriend, Maud (Françoise Fabian), a divorced single mother with open thoughts about sexuality, responsibility, and morality that intrigue Jean-Louis, for whom respectability and appearance are so important. The conversation turns to such topics as hypocrisy, grace, infidelity, and principles, but Maud eventually tires of such talk. “Dialectic does nothing for me,” she says shortly after explaining that she always sleeps in the nude. Later, when Jean-Louis and Maud are alone, she tells him, “You’re both a shamefaced Christian and a shamefaced Don Juan.” Soon a clearly conflicted Jean-Louis is involved in several love triangles that are far beyond his understanding, so he again seeks solace in church. My Night at Maud’s is a classic French tale, with characters spouting off philosophically while smoking cigarettes, drinking wine and other cocktails, and getting naked. Shot in black-and-white by Néstor Almendros, the film roams from midnight mass to a single woman’s bed and back to church, as Jean-Louis, played with expert concern by Trintignant, is forced to examine his own deep desires and how they relate to his spirituality. Fabian (Belle de Jour, The Letter) is outstanding as Maud, whose freedom titillates and confuses Jean-Louis. My Night at Maud’s, which is being shown September 17-18 and 24-25 as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s Six Moral Tales series, is one of Rohmer’s best, most accomplished works despite its haughty intellectualism.

Nominated for the Palme d’Or and a Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, My Night at Maud’s, Éric Rohmer’s fourth entry in his Six Moral Tales series (falling between La Collectionneuse and Claire’s Knee) continues the French director’s fascinating exploration of love, marriage, and tangled relationships. Three years removed from playing the romantic racecar driver Jean-Louis in Claude Lelouch’s A Man and a Woman, Jean-Louis Trintignant again stars as a man named Jean-Louis, this time a single thirty-four-year-old Michelin engineer living a relatively solitary life in the French suburb of Clermont. A devout Catholic, he is developing an obsession with a fellow churchgoer, the blonde, beautiful Françoise (Marie-Christine Barrault), about whom he knows practically nothing. After bumping into an old school friend, Vidal (Antoine Vitez), the two men delve into deep discussions of religion, Marxism, Pascal, mathematics, Jansenism, and women. Vidal then invites Jean-Louis to the home of his girlfriend, Maud (Françoise Fabian), a divorced single mother with open thoughts about sexuality, responsibility, and morality that intrigue Jean-Louis, for whom respectability and appearance are so important. The conversation turns to such topics as hypocrisy, grace, infidelity, and principles, but Maud eventually tires of such talk. “Dialectic does nothing for me,” she says shortly after explaining that she always sleeps in the nude. Later, when Jean-Louis and Maud are alone, she tells him, “You’re both a shamefaced Christian and a shamefaced Don Juan.” Soon a clearly conflicted Jean-Louis is involved in several love triangles that are far beyond his understanding, so he again seeks solace in church. My Night at Maud’s is a classic French tale, with characters spouting off philosophically while smoking cigarettes, drinking wine and other cocktails, and getting naked. Shot in black-and-white by Néstor Almendros, the film roams from midnight mass to a single woman’s bed and back to church, as Jean-Louis, played with expert concern by Trintignant, is forced to examine his own deep desires and how they relate to his spirituality. Fabian (Belle de Jour, The Letter) is outstanding as Maud, whose freedom titillates and confuses Jean-Louis. My Night at Maud’s, which is being shown September 17-18 and 24-25 as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s Six Moral Tales series, is one of Rohmer’s best, most accomplished works despite its haughty intellectualism.

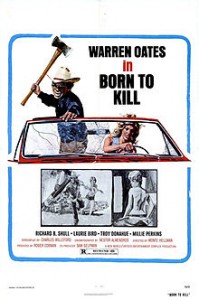

Director Monte Hellman and star Warren Oates enter “the mystic realm of the great cock” in the 1974 cult film Cockfighter. Alternately known as Born to Kill and Gamblin’ Man, the film is set in the world of cockfighting, where Frank Mansfield (Oates) is trying to capture the Cockfighter of the Year award following a devastating loss that cost him his money, car, trailer, girlfriend, and voice — he took a vow of silence until he wins the coveted medal. Mansfield communicates with others via his own made-up sign language and by writing on a small pad; in addition, he delivers brief internal monologues in occasional voiceovers. He teams up with moneyman Omar Baradansky (Richard B. Shull) as he attempts to regain his footing in the illegal cockfighting world, taking on such challengers as Junior (Steve Railsback), Tom (Ed Begley Jr.), and archnemesis Jack Burke (Harry Dean Stanton); his drive for success is also fueled by his desire to finally marry his much-put-upon fiancée, Mary Elizabeth (Patricia Pearcy). The cast also includes Laurie Bird as Mansfield’s old girlfriend, Troy Donahue as his brother, Millie Perkins as his sister-in-law, Warren Finnerty as Sanders, Allman Brothers guitarist Dickey Betts as a masked robber, and Charles Willeford, who wrote the screenplay based on his novel, as Ed Middleton.

Director Monte Hellman and star Warren Oates enter “the mystic realm of the great cock” in the 1974 cult film Cockfighter. Alternately known as Born to Kill and Gamblin’ Man, the film is set in the world of cockfighting, where Frank Mansfield (Oates) is trying to capture the Cockfighter of the Year award following a devastating loss that cost him his money, car, trailer, girlfriend, and voice — he took a vow of silence until he wins the coveted medal. Mansfield communicates with others via his own made-up sign language and by writing on a small pad; in addition, he delivers brief internal monologues in occasional voiceovers. He teams up with moneyman Omar Baradansky (Richard B. Shull) as he attempts to regain his footing in the illegal cockfighting world, taking on such challengers as Junior (Steve Railsback), Tom (Ed Begley Jr.), and archnemesis Jack Burke (Harry Dean Stanton); his drive for success is also fueled by his desire to finally marry his much-put-upon fiancée, Mary Elizabeth (Patricia Pearcy). The cast also includes Laurie Bird as Mansfield’s old girlfriend, Troy Donahue as his brother, Millie Perkins as his sister-in-law, Warren Finnerty as Sanders, Allman Brothers guitarist Dickey Betts as a masked robber, and Charles Willeford, who wrote the screenplay based on his novel, as Ed Middleton.