Spike (Chris O’Shea) and Hilary (Adelaide Clemens) discuss altruism, God, and the prisoner’s dilemma in latest Tom Stoppard masterpiece (photo by Paul Kolnik)

Lincoln Center Theater at the Mitzi E. Newhouse

150 West 65th St. between Broadway & Amsterdam Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through January 6, $92

212-362-7600

www.lct.org

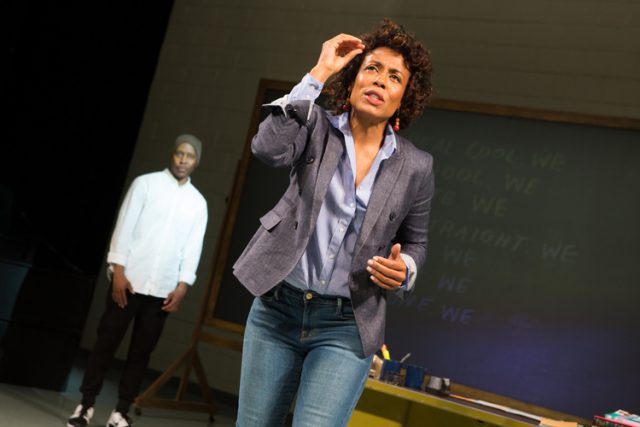

In his first new play since 2006’s Rock ‘n’ Roll, octogenarian genius Tom Stoppard takes a deep dive into nothing less than human consciousness. The opening of The Hard Problem lets us know just what we’re in for: An attractive young tutor and his student hotly debate “the prisoner’s dilemma,” preparing her for a major job interview. We are going to watch characters onstage swim in a British think tank where the big questions are asked. The “hard problem,” of course, is how the biochemistry of organic matter gives rise to consciousness, the realization of a “self” able to reflect on its own existence and concepts of goodness, self-sacrifice, and altruism. Another hard problem, of course, is how to make this cerebral subject work as live theater. Stoppard, who has explored issues of science, chaos theory, philosophy, history, and other intellectual endeavours in such previous works as Arcadia, The Invention of Love, and The Coast of Utopia, achieves his goal this time via a somewhat predictable though cleverly chosen cast of characters: the male “quant” with impeccable academic and professional qualifications who may lack human emotion, the female researcher with a tender heart, strong mind, and wrenching personal history, the overeager postdoctoral assistant, and an old school friend who remains resolutely sensible and cynical.

“It’s about survival strategies hard-wired into our brains millions of years ago. Who eats, who gets eaten, who gets to advance their genes into the next generation,” Spike (Chris O’Shea) tells Hilary Matthews (Adelaide Clemens), who is up for a job at the prestigious Krohl Institute for Brain Science. He continues, “Competition is the natural order. Self-interest is bedrock. Co-operation is a strategy. Altruism is an outlier unless you’re an ant or a bee. You’re not an ant or a bee; you’re competing to do a doctorate at the Krohl Institute, where they’re basically seeing first class honours degrees and you’re in line for a second, so don’t be a smart arse, and above all don’t use the word ‘good’ as though it meant something in evolutionary science.”

Hilary (Adelaide Clemens) listens in as Amal Admati (Eshan Bajpay) and Dr. Leo Reinhart (Robert Petkoff) have quite a disagreement in The Hard Problem (photo by Paul Kolnik)

Hilary has just about everything going against her: She went to the wrong schools, didn’t do the expected internships, didn’t ace the proper tests, and has different ideas about the mind and consciousness than does Amal Admati (Eshan Bajpay), who is seemingly the perfect candidate for the job — but Dr. Leo Reinhart (Robert Petkoff) chooses Hilary for the position because of her rather unique and somewhat unscientific thoughts on the relationship between the brain and consciousness. It all comes to a head when the fiercely ambitious Bo (Karoline Xu) joins Hilary’s team and takes the lead on a complex project that doesn’t go quite as planned.

Bo (Karoline Xu) complicates things for Hilary (Adelaide Clemens) in New York premiere of The Hard Problem at Lincoln Center (photo by Paul Kolnik)

Despite all the talk of statistical tendencies, evolutionary behavior, moral intelligence, computer programming, binary operations, egoism, and other high-falutin’ terms, Stoppard is not so much interested in science than in personality; the characters in the play are splendidly drawn, from Jerry Krohl (Jon Tenney), who Spike describes as “a squillionaire with a masters in biophysics who decided to try hedge-funding,” and Jerry’s bright young daughter, Cathy (Katie Beth Hall), to Julia Chamberlain (Nina Grollman), a former classmate of Hilary’s who runs Pilates classes at the institute — serving the body in a place built around the mind — and Julia’s partner, Ursula Tarrant (Tara Summers), who doesn’t shy away from discussing panpsychism. Stoppard also explores the idea of a supreme being among all this science. “How does God feel about your model of Nature-Nurture Convergence in Altruistic Parent-Offspring Behaviour?” Spike asks Hilary, who prays every night before she goes to bed. But Hilary and Stoppard are concerned with more down-to-earth subjects. “Who’s the you outside your brain? Where? The mind is extra,” Hilary says.

Three-time Tony-winning director Jack O’Brien (Hairspray, Hapgood), who has helmed such other major Stoppard works as The Coast of Utopia and The Invention of Love, has a clear handle on the material, never allowing the play to get overly pedantic, keeping it all real on David Rockwell’s cool set, in which props and furniture are wheeled on or off or drop from the ceiling. Various cast members sit on a couch watching when they’re not involved in the action, taking in every poetic phrase just as we are. Clemens (Hold on to Me Darling, Rectify) is a revelation as Hilary, an unpredictable, fascinating woman who in many ways is representative of the average, regular person facing a changing world. “Explain consciousness,” Hilary says early on to Spike, who doesn’t have an answer. In The Hard Problem, Stoppard isn’t seeking answers but is asking all the right questions.