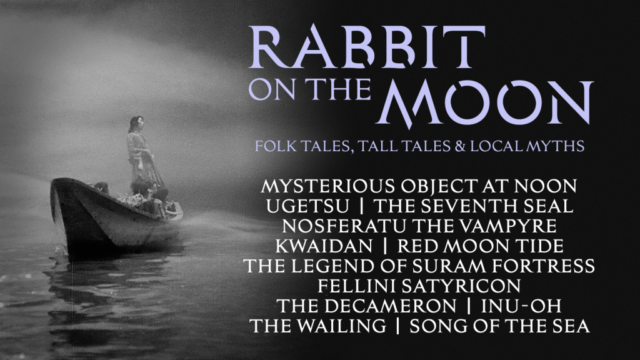

RABBIT ON THE MOON

Metrograph

7 Ludlow St. between Canal & Hester Sts.

September 6-29

212-660-0312

metrograph.com

The Metrograph series “Rabbit on the Moon: Folk Tales, Tall Tales, and Local Myths” consists of a dozen international films inspired by folklore from around the world. The works explore traditional stories from Sweden, Japan, Thailand, Georgia, Ireland, Germany, Italy, and South Korea, by some of the most important auteurs of the last seventy-five years.

Among the films are Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Decameron, Federico Fellini’s Fellini Satyricon, Sergei Parajanov and Dodo Abashidze’s The Legend of Suram Fortress, Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Mysterious Object at Noon, Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre, Tomm Moore’s Song of the Sea, Na Hong-jin’s The Wailing, and Lois Patiño’s Red Moon Tide. Below is a look at several favorites.

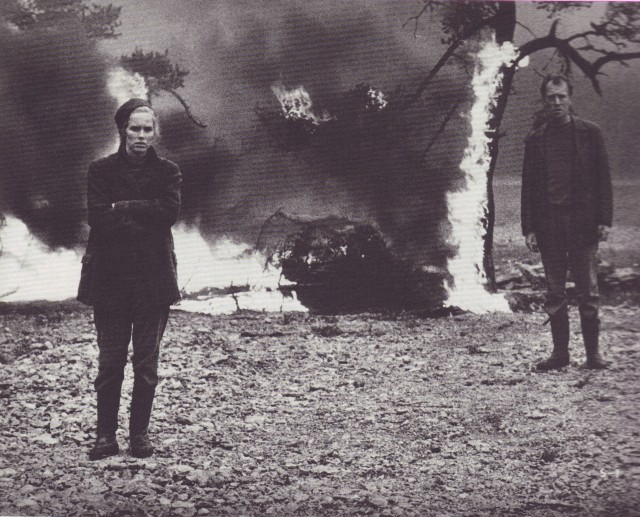

Antonius Block (Max von Sydow) sits down with Death (Bengt Ekerot) for a friendly game of chess in Bergman classic

THE SEVENTH SEAL (Ingmar Bergman, 1957)

Friday, September 6, 2:50

Sunday, September 8, 5:30

metrograph.com

It’s almost impossible to watch Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal without being aware of the meta surrounding the film, which has influenced so many other works and been paid homage to and playfully mocked. Over the years, it has gained a reputation as a deep, philosophical paean to death. However, amid all the talk about emptiness, doomsday, the Black Plague, and the devil, The Seventh Seal is a very funny movie. In fourteenth-century Sweden, knight Antonius Block (Max von Sydow) is returning home from the Crusades with his trusty squire, Jöns (Gunnar Björnstrand). Block soon meets Death (Bengt Ekerot) and, to prolong his life, challenges him to a game of chess. While the on-again, off-again battle of wits continues, Death seeks alternate victims while Block meets a young family and a small troupe of actors putting on a show. Rape, infidelity, murder, and other forms of evil rise to the surface as Block proclaims “To believe is to suffer,” questioning God and faith, and Jöns opines that “love is the blackest plague of all.” Based on Bergman’s own play inspired by a painting of Death playing chess by Albertus Pictor (played in the film by Gunnar Olsson), The Seventh Seal, winner of a Special Jury Prize at Cannes, is one of the most entertaining films ever made. (Bergman fans will get an extra treat out of the knight being offered some wild strawberries at one point.)

Genjurō (Masayuki Mori) makes his pottery as son Genichi (Ikio Sawamura) and wife Miyagi (Kinuyo Tanaka) look on in Ugetsu

UGETSU (UGETSU MONOGATARI) (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1953)

Friday, September 13, 2:00

Sunday, September 15, 9:30

metrograph.com

The Metrograph series includes one of the most important and influential — and greatest — works to ever come from Japan. Winner of the Silver Lion for Best Director at the 1953 Venice Film Festival, Kenji Mizoguchi’s seventy-eighth film, Ugetsu, is a dazzling masterpiece steeped in Japanese storytelling tradition, especially ghost lore. Based on two tales by Ueda Akinari and Guy de Maupassant’s “How He Got the Legion of Honor,” Ugetsu unfolds like a scroll painting beginning with the credits, which run over artworks of nature scenes while Fumio Hayasaka’s urgent score starts setting the mood, and continues into the first three shots, pans of the vast countryside leading to Genjurō (Masayuki Mori) loading his cart to sell his pottery in nearby Nagahama, helped by his wife, Miyagi (Kinuyo Tanaka), clutching their small child, Genichi (Ikio Sawamura). Miyagi’s assistant, Tōbei (Sakae Ozawa), insists on coming along, despite the protestations of his nagging wife, Ohama (Mitsuko Mito), as he is determined to become a samurai even though he is more of a hapless fool. “I need to sell all this before the fighting starts,” Genjurō tells Miyagi, referring to a civil war that is making its way through the land. Tōbei adds, “I swear by the god of war: I’m tired of being poor.” After unexpected success with his wares, Genjurō furiously makes more pottery to sell at another market even as the soldiers are approaching and the rest of the villagers run for their lives. At the second market, an elegant woman, Lady Wakasa (Machiko Kyō), and her nurse, Ukon (Kikue Mōri), ask him to bring a large amount of his merchandise to their mansion. Once he gets there, Lady Wakasa seduces him, and soon Genjurō, Miyagi, Genichi, Tōbei, and Ohama are facing very different fates.

Lady Wakasa (Machiko Kyō) admires Genjurō (Masayuki Mori) in Kenji Mizoguchi postwar masterpiece

Written by longtime Mizoguchi collaborator Yoshitaka Yoda and Matsutaro Kawaguchi, Ugetsu might be set in the sixteenth century, but it is also very much about the aftereffects of World War II. “The war drove us mad with ambition,” Tōbei says at one point. Photographed in lush, shadowy black-and-white by Kazuo Miyagawa (Rashomon, Floating Weeds, Yojimbo), the film features several gorgeous set pieces, including one that takes place on a foggy lake and another in a hot spring, heightening the ominous atmosphere that pervades throughout. Ugetsu ends much like it began, emphasizing that it is but one postwar allegory among many. Kyō (Gate of Hell, The Face of Another) is magical as the temptress Lady Wakasa, while Mori (The Bad Sleep Well, When a Woman Ascends the Stairs) excels as the everyman who follows his dreams no matter the cost; the two previously played husband and wife in Rashomon. Mizoguchi, who made such other unforgettable classics as The 47 Ronin, The Life of Oharu, Sansho the Bailiff, and Street of Shame, passed away in 1956 at the age of fifty-eight, having left behind a stunning legacy, of which Ugetsu might be the best, and now looking better than ever following a recent 4K restoration.

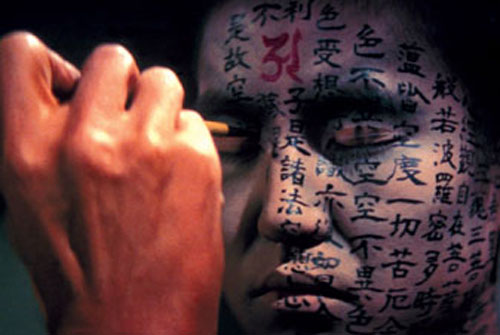

Tōru Takemitsu “wanted to create an atmosphere of terror” in Masaki Kobayashi’s quartet of ghost stories

KWAIDAN (Masaki Kobayashi, 1964)

Saturday, September 21, 9:30

metrograph.com

Masaki Kobayashi paints four marvelous ghost stories in this eerie collection that won a Special Jury Prize at Cannes. In “The Black Hair,” a samurai (Rentaro Mikuni) regrets his choice of leaving his true love for advancement. Yuki (Keiko Kishi) is a harbinger of doom in “The Woman of the Snow.” Hoichi (Katsuo Nakamura) must have his entire body covered in prayer in “Hoichi, the Earless.” And Kannai (Kanemon Nakamura) finds a creepy face staring back at him in “In a Cup of Tea.” Winner of the Special Jury Prize at Cannes, Kwaidan is one of the greatest ghost story films ever made, four creepy, atmospheric existential tales that will get under your skin and into your brain. The score was composed by Tōru Takemitsu, who said of the film, “I wanted to create an atmosphere of terror.” He succeeded.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]

The New York Film Festival’s Retrospective tribute to cinematographers continues October 2 with The Passion of Anna, the conclusion to Ingmar Bergman’s unofficial island trilogy that began with

The New York Film Festival’s Retrospective tribute to cinematographers continues October 2 with The Passion of Anna, the conclusion to Ingmar Bergman’s unofficial island trilogy that began with

Film Forum’s Ingmar Bergman Centennial Retrospective continues with Bergman’s darkly comic 1958 film The Magician, one of the Swedish auteur’s lesser-known, underrated masterpieces, an intense yet funny, and fun, work about art, science, faith, death, and the power of the movies themselves. When Vogler’s Magnetic Health Theater comes to town, the local triumvirate of Dr. Vergérus (Gunnar Björnstrand), police commissioner Starbeck (Toivo Pawlo), and Consul Egerman (Erland Josephson) brings the traveling troupe in for questioning, forcing them to spend the night as guests in Egerman’s home. The three men seek to prove that mesmerist Albert Emanuel Vogler (Max von Sydow), his assistant, Mr. Aman (Ingrid Thulin), a witchy grandmother (Naima Wifstrand), and their promoter, Tubal (Åke Fridell), are a bunch of frauds. The interrogations delve into such Bergmanesque topics as science vs. reason, good vs. evil, life and death, and the existence of God. As various potions are dispensed to and tricks played on a staff that includes maid Sara (Bibi Andersson), cook Sofia Garp (Sif Ruud), and stableman Antonsson (Oscar Ljung) in addition to Starbeck’s wife (Ulla Sjöblom) and Egerman’s spouse (Gertrud Fridh), a series of romantic rendezvous take place, along with some genuine horror, leading to a thrillingly ambiguous ending.

Film Forum’s Ingmar Bergman Centennial Retrospective continues with Bergman’s darkly comic 1958 film The Magician, one of the Swedish auteur’s lesser-known, underrated masterpieces, an intense yet funny, and fun, work about art, science, faith, death, and the power of the movies themselves. When Vogler’s Magnetic Health Theater comes to town, the local triumvirate of Dr. Vergérus (Gunnar Björnstrand), police commissioner Starbeck (Toivo Pawlo), and Consul Egerman (Erland Josephson) brings the traveling troupe in for questioning, forcing them to spend the night as guests in Egerman’s home. The three men seek to prove that mesmerist Albert Emanuel Vogler (Max von Sydow), his assistant, Mr. Aman (Ingrid Thulin), a witchy grandmother (Naima Wifstrand), and their promoter, Tubal (Åke Fridell), are a bunch of frauds. The interrogations delve into such Bergmanesque topics as science vs. reason, good vs. evil, life and death, and the existence of God. As various potions are dispensed to and tricks played on a staff that includes maid Sara (Bibi Andersson), cook Sofia Garp (Sif Ruud), and stableman Antonsson (Oscar Ljung) in addition to Starbeck’s wife (Ulla Sjöblom) and Egerman’s spouse (Gertrud Fridh), a series of romantic rendezvous take place, along with some genuine horror, leading to a thrillingly ambiguous ending.

Film Forum is celebrating the centennial of Swedish master Ingmar Bergman’s birth with a five-week retrospective of nearly four dozen films he directed and/or wrote, forty of which are new restorations from the Swedish Film Institute. The series, running from February 7 through March 15, kicks off with one of the greatest and most influential films ever made, 1957’s The Seventh Seal, in which an errant knight played by Max von Sydow sits down for a game of chess with Death (Bengt Ekerot), as well as the intense 1944 expressionistic noir, Frenzy. Although directed by Alf Sjöberg, Frenzy, also known as Torment, was written by Bergman, who also served as assistant director and made his directing debut in the final scene, which Bergman added at the insistence of the producers when Sjöberg was not available. A kind of inversion of Josef von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel, the film is set in a boarding school where high school boys are preparing for their final exams and graduation. They are terrified of their sadistic Latin teacher, whom they call Caligula (Stig Järrel), a brutal man who wields a fascistic iron fist. He particularly has it out for Jan-Erik Widgren (Alf Kjellin), the son of wealthy parents (Olav Riégo and Märta Arbin) who think he should be doing better in school. One night Jan-Erik helps out a troubled woman in the street, tobacco-shop clerk Bertha Olsson (Mai Zetterling), who is being mentally and physically tormented by an unnamed man who ends up being Caligula. The stakes get higher and the teacher becomes even harder on Jan-Erik when he finds out the young man is having an affair with the wayward woman. When tragedy strikes, Jan-Erik’s soul is in turmoil as lies, threats, and danger grow.

Film Forum is celebrating the centennial of Swedish master Ingmar Bergman’s birth with a five-week retrospective of nearly four dozen films he directed and/or wrote, forty of which are new restorations from the Swedish Film Institute. The series, running from February 7 through March 15, kicks off with one of the greatest and most influential films ever made, 1957’s The Seventh Seal, in which an errant knight played by Max von Sydow sits down for a game of chess with Death (Bengt Ekerot), as well as the intense 1944 expressionistic noir, Frenzy. Although directed by Alf Sjöberg, Frenzy, also known as Torment, was written by Bergman, who also served as assistant director and made his directing debut in the final scene, which Bergman added at the insistence of the producers when Sjöberg was not available. A kind of inversion of Josef von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel, the film is set in a boarding school where high school boys are preparing for their final exams and graduation. They are terrified of their sadistic Latin teacher, whom they call Caligula (Stig Järrel), a brutal man who wields a fascistic iron fist. He particularly has it out for Jan-Erik Widgren (Alf Kjellin), the son of wealthy parents (Olav Riégo and Märta Arbin) who think he should be doing better in school. One night Jan-Erik helps out a troubled woman in the street, tobacco-shop clerk Bertha Olsson (Mai Zetterling), who is being mentally and physically tormented by an unnamed man who ends up being Caligula. The stakes get higher and the teacher becomes even harder on Jan-Erik when he finds out the young man is having an affair with the wayward woman. When tragedy strikes, Jan-Erik’s soul is in turmoil as lies, threats, and danger grow.