A teenage farm girl (Condola Rashad) is on a mission from God in Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan (photo by Joan Marcus)

Manhattan Theatre Club at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

261 West 47th St. between Broadway & Eighth Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through June 10, $65-$159

saintjoanbroadway.com

www.manhattantheatreclub.com

“There is something about her,” men say of Saint Joan, the title character in Bernard Shaw’s 1923 play. There is also something about Condola Rashad, who portrays Joan in the current Manhattan Theatre Club revival at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre. Rashad has now appeared in five Broadway shows, earning four Tony nominations, for Stick Fly, The Trip to Bountiful, A Doll’s House, Part 2, and Saint Joan. (She was also nominated for a Drama Desk Award for her 2009 off-Broadway debut, Ruined, but got shut out as Juliet in a misbegotten Broadway revival of Romeo and Juliet in 2013.) The thirty-one-year-old Rashad is charming as Joan, a teenage farm girl in 1429 who claims that Saint Margaret and Saint Catherine speak to her and that God has commanded her to lead the French to victory in Orleans against the occupying English so the hapless Dauphin (Adam Chanler-Berat) can claim the throne as King Charles VII. She joins a luminous roster of actresses who have played Saint Joan, including Wendy Hiller, Uta Hagen, Joan Plowright, Jean Seberg, Imelda Staunton, Imogen Stubbs, Amy Irving, and Diana Sands, the only other black woman to portray Joan in a major production, at Lincoln Center in 1968. Rashad’s Joan is sweet-natured but determined, gentle yet forceful, a kind of hero just right for the #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter generation. Joan goes about the world of men — Rashad is the only woman in the cast, among twelve actors, save for a brief appearance by Mandi Masden as the Duchess de la Trémouille — with an ease that emanates from her faith.

Military squires, royals, and religious leaders disparage Joan until they meet her, slowly falling under her captivating spell. Robert de Baudricourt (Patrick Page) brags about how he “burns witches and hangs thieves,” but Joan tells him, “They all say I am mad until I talk to them, squire. But you see that it is the will of God that you are to do what He has put into my mind,” and he does. Captain La Hire (Lou Sumrall) calls her “an angel dressed as a soldier.” Charles might not want to be king, but Joan is on a holy mission to see that he is crowned at Rheims Cathedral. “If the English win, it is they that will make the treaty: and then God help poor France!” she tells Charles. “You must fight, Charlie, whether you will or no. I will go first to hearten thee. We must take our courage in both hands: aye, and pray for it with both hands too.” But after she impossibly takes Orleans despite being massively outnumbered and then urges the campaign continue on to recapture Paris, the military, the church, and the monarchy realize her power and turn on her, trying her for sins that could get her burned at the stake.

The Dauphin (Adam Chanler-Berat) finds a savior in Joan (Condola Rashad) in Manhattan Theatre Club Broadway revival (photo by Joan Marcus)

Scott Pask’s set is dominated by large gold pipes hanging from above, as if the entire play takes place inside a giant church organ, spreading Joan’s religious message. “It is in the bells I hear my voices,” Joan tells Jack Dunois (Daniel Sunjata), who ably fights by her side. “Not today, when they all rang: that was nothing but jangling. But here in this corner, where the bells come down from heaven, and the echoes linger, or in the fields, where they come from a distance through the quiet of the countryside, my voices are in them.” Shaw (who preferred not to use the first name George) famously said, “I’m an atheist and I thank God for it”; in writing the play, he was trying to neither convert anyone nor convince them to leave the fold, nor was he creating a biblical-style story of good versus evil. In a preface to the published edition, Shaw wrote, “There are no villains in the piece. . . . It is what men do at their best, with good intentions, and what normal men and women find that they must and will do in spite of their intentions, that really concern us.” Shaw, who also wrote such works as Pygmalion, Major Barbara and Man and Superman and won the Nobel Prize shortly after Saint Joan, does not include any superheroes either. “I am not a daredevil: I am a servant of God,” Joan says to Dunois. “My heart is full of courage, not of anger. I will lead; and your men will follow: that is all I can do. But I must do it: you shall not stop me.”

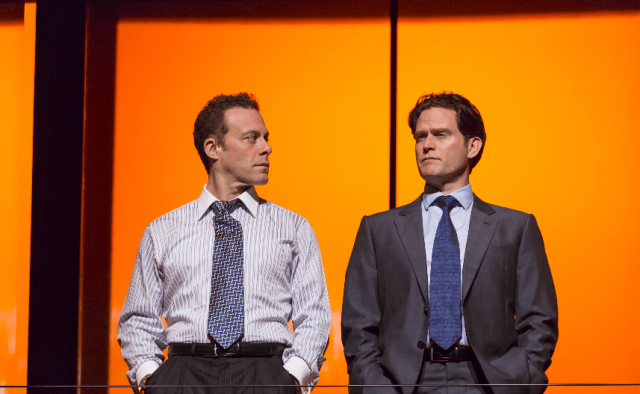

The exemplary cast also features Max Gordon Moore as Bluebeard, Walter Bobbie as the Bishop of Beauvais, John Glover as the Archbishop of Rheims, Matthew Saldivar as Bertrand de Poulengey, Robert Stanton as Baudricourt’s steward, Russell G. Jones as Monseigneur de la Trémouille, and Jack Davenport as the Earl of Warwick. Most of the actors play more than one role; Page is particularly impressive as Baudricourt and the Inquisitor. Daniel Sullivan’s (The Little Foxes, Proof) direction can get a little bumpy though there are several deft touches, and at nearly three hours, the show can be a little trying. Which brings us to the rather campy epilogue. Shaw wrote Saint Joan in 1923, three years after her canonization, something he deals with in the somewhat surreal, comic, and arguably out-of-place conclusion. “As to the epilogue, I could hardly be expected to stultify myself by implying that Joan’s history in the world ended unhappily with her execution, instead of beginning there,” Shaw wrote. “It was necessary by hook or crook to shew the canonized Joan as well as the incinerated one; for many a woman has got herself burnt by carelessly whisking a muslin skirt into the drawing-room fireplace, but getting canonized is a different matter, and a more important one. So I am afraid the epilogue must stand.” And so it does, for better or worse.